The fight for global economic power is being fought in two giant arenas: world commerce, with the US-China trade war; and Eurasia, with China’s Belt and Road initiative. Meanwhile, Washington has trumpeted “energy dominance” on the back of its shale oil and gas resources. But the master of the new energy economy may instead be Beijing, and in quite a different way from traditional dominance.

Under President Donald Trump, and his anti-China advisers such as Peter Navarro and Robert Lighthizer, the US has sought to stymie China’s economic rise. Part of this has concentrated on future technologies, in fields such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, telecoms and encryption. Washington has sought to persuade historic allies not to use products of Chinese tech giant Huawei over security fears. Some hardliners seek to “decouple” the two countries’ entwined technology sectors.

Commodities have been another part of the trade war. Energy, minerals, metals, chemicals and agricultural produce made up more than half of US exports to China, before Beijing imposed retaliatory tariffs. Its imports of American oil and liquefied natural gas have now fallen close to zero. US sanctions on Iran, most recently on a number of Chinese shipping lines carrying Iranian crude, have disrupted the tanker market and reduced Chinese imports of Iranian oil, but Beijing remains Tehran's only significant customer.

But China has at least four levers of power over the emerging energy economy. Firstly, and least importantly, is its control of raw materials. It is the world’s largest reserves holder, producer and processor of rare earth elements (REEs) and graphite, and an important miner of lithium, all materials used in the future energy economy for batteries, high-power electric motors, solar cells, wind turbines and superconductors.

China has at times sought to leverage this power by restricting REE exports to harm its competitor, Japan, and build up domestic processing capability. But this has so far backfired. The US has stockpiled REEs crucial for its military, new mines have been opened elsewhere, and the quantity of sensitive minerals in new technologies has been designed down or substituted.

The second is both a strength and a weakness. The Middle Kingdom has become the world’s largest importer of oil and gas. This is a strategic vulnerability for an aspiring superpower, when the US continues to hold the keys of the Arabian Gulf, the Gulf of Mexico, and marine chokepoints throughout Asia including the Strait of Malacca.

But it makes China the key export destination for Russia, Australia, Brazil and most Middle East countries. The leading oil and gas exporters have sought to enter joint ventures in refining and petrochemicals in China, and Chinese companies have entered the upstream sector in Abu Dhabi, Iraq, Iran and Egypt.

Russia, meanwhile, is a close partner of China, but increasingly a junior one, and was reliant on Chinese investment to help it advance projects, such as its mega-scale Arctic LNG venture, when sanctions halted the flow of western funds.

This mutual interdependence may draw China into closer business, political and even military involvement in the Middle East and Central Asia. It may find its interests clashing with those of the US and another emerging Asian giant, India. And like Russia, it may find it unsustainable to be friendly forever with a number of countries that are themselves opposed to one another.

The third is the Belt and Road plan. This complex and amorphous group of projects for connectivity throughout Eurasia and the Indian Ocean has a major energy component: ports; LNG terminals; power plants; pipelines and railways. For electricity, State Grid Corporation wants to build a $300 billion (Dh1.1 trillion) ultra-high voltage grid linking most of Asia. The Belt and Road is designed partly to ensure reliable overland and marine access for China to energy, particularly from Russia and Central Asia; and partly to export Chinese skills and industrial overcapacity.

China is stepping up its gas imports to improve air quality. Yet in a world looking to be green, it is notable that its international power plans concentrate mostly on coal, the dirtiest fuel, and environmentally-disruptive hydropower, two areas where it has most experience. Belt and Road projects have also suffered from local opposition, poor commercial fundamentals, lack of institutional underpinning, and worries over "debt traps" and excessive Chinese dominance of the economies of countries such as Malaysia and Burma.

A China monopoly would powerfully shape Eurasia's energy future. In September, Japan and the EU signed a deal, dovetailing with a €60 billion (Dh244.18bn) European initiative, that could bring quite a different vision founded on environmental and social sustainability, multipolarity and trade openness. Meanwhile, America first is America alone.

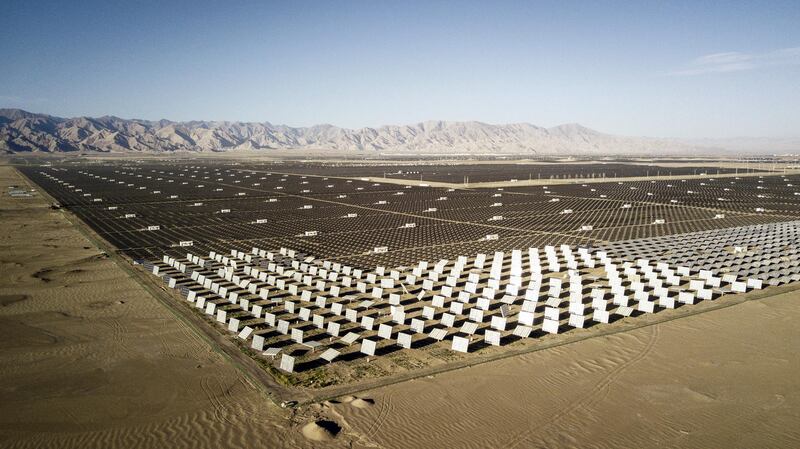

China’s fourth lever is its strongest: its technological and manufacturing prowess. It has the top nine solar module suppliers, five of the leading 10 electric vehicle manufacturers, three of the biggest five lithium ion battery makers, and three of the top 10 wind turbine makers.

After failing to develop a leading domestic conventional car maker, it sees battery cars as a way to leapfrog competitors, and with more than a million sales last year, it is by far the world’s biggest market, three times the size of Europe or the US. Electric mobility will help clean up its polluted skies, and free its economy from vulnerability to cut-offs of oil imports.

China’s power over the future energy economy may not endure; it may not be able to sustain its innovative edge, or other breakthrough centres may emerge. Its ability to shape technology that suits itself, or to deny exports to rivals, is very different from the ability to cut off oil or gas overnight. But China’s pursuit of new energy may soon outstrip the US’s wannabe dominance of the old.

Robin Mills is the chief executive of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis