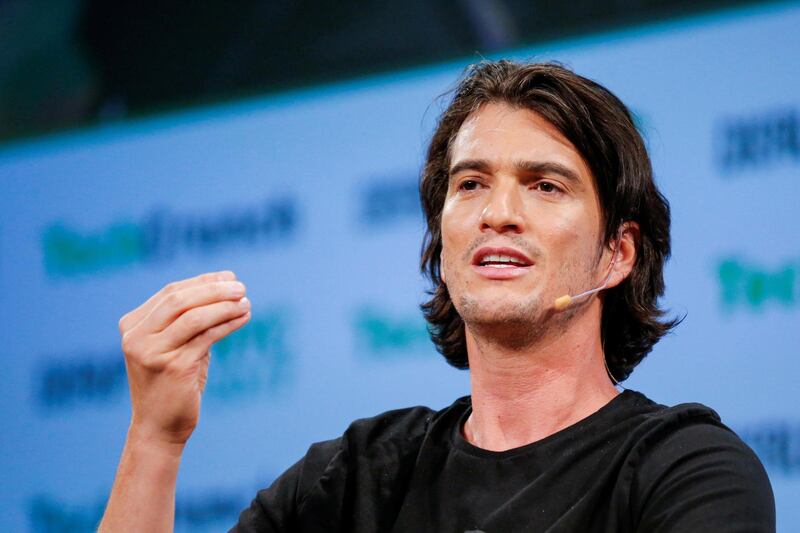

The knives are out for WeWork chief executive Adam Neumann.

With the drama of a palace coup, some directors are considering a plan to encourage the brash co-founder of the once high-flying real estate start-up to step down as chief executive, according to sources. Among them: Masayoshi Son, the founder of SoftBank Group, WeWork’s biggest investor, a source said.

The board plans to meet on Monday in what would be a remarkable showdown between Mr Neumann, 40, and his billionaire backer. The directors are said to be considering asking him to become non-executive chairman.

Time is short and bankers are anxiously awaiting their next move. The company must complete its initial public offering before the end of the year to keep access to a crucial $6 billion (Dh22.03bn) loan.

WeWork conceded last week that its grandiose plans for going public would have to wait after talks with potential investors lowered expectations for the company’s planned IPO valuation to $15bnor less. Among the concerns they voiced: Mr Neumann’s controversial style and control of the company.

Rarely has so much gone so wrong so fast for a young company in the spotlight.

“It’s Uber-scale mess,” said Kellie McElhaney, a professor at the University of California Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, who blames both the board and Mr Neumann for not learning from that company’s earlier mistakes. “He’s really taken a first-mover advantage that WeWork had in the space and blown it in a big way.”

The WeWork story is beginning to fit squarely into the era of unicorn capitalism: a young and charismatic entrepreneur disrupts an industry, runs afoul of elders and investors, sometimes winning but sometimes failing to live up to their own hype.

Institutions including Benchmark Capital, one of WeWork’s investors, pushed out Uber Technologies’ Travis Kalanick before the ride-hailing company went public.

Still, even if some directors want to oust Mr Neumann, it won’t be easy given the company’s governance structure. Based on the number of shares he controls and their unique super-voting rights, Mr Neumann has the power to get rid of the entire board on his own, according to the prospectus.

Softbank’s intervention in the WeWork saga comes as the biggest backers of the company’s gargantuan Vision Fund are reconsidering how much to commit to its next investment vehicle.

The news of Mr Neumann’s potential ouster comes after a whirlwind week of uncertainty for WeWork. Banks that provided a $500 million credit line to Mr Neumann are looking to revise the terms as the company’s struggle to go public casts doubt on the value of his collateral, people briefed on the discussions said last week. It’s not clear what changes they may seek, or what right they may have to make demands.

Last week, Wendy Silverstein, a big name in New York commercial real estate who joined WeWork last year as head of its property investment arm, left the company. She’s spending time caring for her elderly parents.

Even the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston was adding to the angst. In a speech Friday in New York, Eric Rosengren warned that the proliferation of co-working spaces might pose new risks to financial stability.

“I’ve never seen a company of this size and scale generate such a consensus of negative opinion in my long, long life of following IPOs,” said Len Sherman, a Columbia Business School adjunct professor whose 30-year business career included time as a senior partner at consulting firm Accenture. “There is no box that they haven’t ticked when you think of all the reasons that you might be very concerned — like blaring red lights. Like, oh my gosh, caution, danger, danger.”