Without support from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and foreign donors, Lebanon’s economic crisis is likely to worsen, destabilising the peg of its currency to the US dollar, Moody’s Investors Service said.

Though the request for assistance by caretaker prime minister Saad Hariri to both organisations and donors last week is credit positive without their “technical and financial support … a scenario of extreme macroeconomic instability – in which a debt restructuring occurs with an abrupt destabilisation of the currency peg resulting in very large losses for private investors – is increasingly likely,” Moody’s said.

Mr Hariri reached out for assistance last week after Moody’s and Fitch warned of a deterioration in the commercial strength of Lebanon’s top banks, a cornerstone of the country’s economy, following instructions by the central bank that they reduce interest rates by half on foreign and local currency deposits. The directive came as the regulator tries to restore confidence amid the worst financial crisis the country has faced since the end of a 15-year civil war in 1990.

Lebanon has one of the highest debt-to-gross domestic product debt ratios in the world at 150 per cent of GDP with a public debt of $86 billion (Dh316bn). Though the country paid $1.5bn of maturing debt last month, it has $1.2bn due in March when a Eurobond hits maturity. Another $700 million is due in April and $600m in June. The crisis has increased the yield on the country’s bonds and led to the Lebanese pound to lose a third of its value against the dollar in the local black market.

“A growing foreign-currency shortage in Lebanon's highly import-dependent economy points to diminishing options for the central bank to ensure currency stability,” Moody’s said. “The increasing foreign-currency shortage for daily business transactions has given rise to a shadow exchange rate that is currently trading at around 2,000 pound to the US dollar, compared with the official rate of LBP1,507.5”.

Though the central bank has said it will not impose capital control measures banks have implemented their own measures, imposing weekly withdrawal limits in addition to reducing lines on credit cards.

The formation of a new government and implementation of structural reforms tied to $11bn pledged by donors last year at a Paris conference “are increasingly urgent,” Moody’s said. Based on economic data of the past 10 months Lebanon’s economy is projected to contract 2.5 per cent in 2019 and by 1.5 per cent in 2020, it added.

Lebanon's debt burden will continue to rise with a fiscal deficit of 11.5 per cent forecast for this year and 10 per cent in 2020 “in light of lower nominal growth, underpinning the international donor community's demand for a debt-management strategy,” the agency said.

Lebanon was able to escape the 2008 global credit crisis relatively unscathed due to a high interest rate regime that lured more than $1bn a month in capital flows. After years of economic expansion following a month-long war in 2006 and a political vacuum that left it without a president on two occasions and led to civil strife, economic growth decelerated to 0.3 per cent last year, according to the IMF.

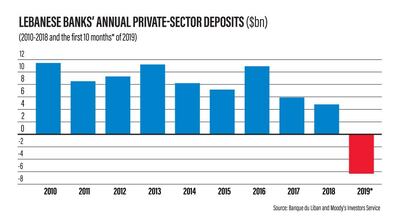

Consumer and investor confidence have ebbed, bank deposits, which underpin the ability of the government to service its fiscal, and current account deficits have declined.

Bank deposits declined an average $6.3bn, or 3.6 per cent, in the 10 months to October 2019 with $2.0bn leaving the banking system in October alone, according to official central bank data and Moody’s.