India urgently needs to find solutions to address the credit crunch in the country that is hurting businesses and crimping growth in Asia's third-largest economy, according to analysts.

“The crisis needs to be tackled on a priority basis,” says Mahesh Singhi, the founder and managing director of Singhi Advisors, an investment bank based in Mumbai. “If left unchecked, we are looking at massive layoffs across industries, triggering a large-scale job [market] crisis, contraction in consumer demand and an investment slowdown.”

The credit crisis in India that is rooted in non bank financial companies (NBFCs), commonly known as shadow banks, began in 2018 when one of the sector's biggest companies, IL&FS, unexpectedly defaulted on loans. It is often referred to as India's “Lehman moment” - a reference to the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers synonymous with the beginning of the global financial crisis.

The troubles at IL&FS spooked investors and lenders alike and the flow of cash in the system slowed to a trickle as capital markets became wary of extending financing to these institutions.

This came against a backdrop of India's banking sector facing its own set of challenges.

Laden with high levels of bad debts, it was only logical for the lenders to minimise their exposure to shadow banking institutions. The Indian government, over the past couple of years, has injected billions of dollars into public sector banks, helping them to clean up their balance sheets and implement reforms. The key pillar of these reforms is prudent future lending to prevent amassing further bad loans.

Businesses in India, whether shadow banking institutions or corporate sector firms, are finding it "increasingly difficult and expensive to access credit”, says Mr Singhi.

“Weakened liquidity position of financial institutions [banks] has constrained their ability to extend credit reach to corporates,” he adds.

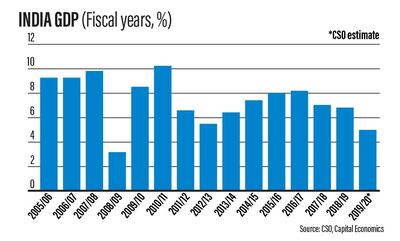

The impact of the credit crisis is all too visible on the Indian economy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its updated World Economic Outlook on Monday cut its growth forecast for India to 4.8 per cent from an earlier projection of 6.1 per cent for the current financial year, which runs until the end of March.

“Domestic demand has slowed more sharply than expected amid stress in the non-bank financial sector and a decline in credit growth,” according to the IMF.

Analysts say that India is now caught in a vicious cycle.

“It is definitely not a conducive environment for businesses and the economy when the credit flow slows. And, its impact is clearly visible on GDP numbers and other macro indicators,” says Ajit Mishra, a research vice president at New Delhi-based securities firm Religare Broking. “The ongoing economic slowdown has made it even worse for securing credit as the lenders turn more cautious during the slowdown. As a result, we are seeing more companies are finding it difficult to access credit.”

The government is due to announce its annual budget on February 1, an opportunity for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman to lay out what the government intends to do to improve liquidity in the system.

There is some speculation among analysts that the government could make it easier for Indian companies to secure funding from abroad. It may possibly offer tax breaks to global funds and could also relax rules to allow Indian firms to borrow at higher rates from overseas, opening a door for them to tap international debt markets by selling bonds.

“The government needs to step up the pace of recapitalising public sector banks, improving the asset quality of banks, and facilitate large-scale foreign investment in the economy,” says Mr Singhi.

Although there is pressure on New Delhi to do more, policymakers in the capital have already taken steps to address the liquidity issues over the past few months. They also plan to merge 10 state-owned banks into four financial institutions in a bid to increase the size of their balance sheets and boost credit flows in the system.

It rolled out a $1.4 billion (Dh5.14bn) real estate fund in September to help the ailing property sector. The real estate industry, which is particularly dependent on credit, will be able to access last-mile financing through the fund to complete stalled housing projects.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the central bank of the country, has also rolled out measures to directly address the challenges in the non-banking financial sector. Relaxations for securitisation of assets for NBFCs, is among the steps take by the central bank to improve liquidity. It is also closely monitoring the performance and health of the country's 50 largest NBFCs.

The RBI “wherever necessary, will not hesitate to act to ensure that we do not allow any large or systemically important NBFC to collapse and create any adverse impact on the system”, the central bank governor Shaktikanta Das said last month, following the RBI's monetary policy meeting.

The RBI last year cut interest rates five times, as it tried to get money flowing again. But lenders have been slow to pass on lower rates to their customers. The central bank last month also launched a series of auctions, dubbed by the market as “Operation Twist”, which involves simultaneous buying and selling of bonds in a bid to bring down interest rates.

“Such announcements and measures take time to reflect on the ground,” says Mr Mishra. “We feel the measures announced by the government and RBI may take a quarter or two to show the results.”

Sectors that are particularly affected by the crisis are those that depend on credit, such as the car industry, which saw hundreds and thousands of job losses last year.

“Lack of supply of credit in any economy hurts growth, so it did in India,” says Vikas Khemani, the founder of Carnelian Capital, an asset management firm based in Mumbai. “The auto sector and housing, which largely depends on credit for demand got hit hard, creating a cascading effect in the economy.”

The efforts by the government, he says, have stared to show some signs of improvement in liquidity.

“That’s what is happening, although in a very slow manner through measures such as the real estate fund, credit guarantee to NBFCs,” says Mr Khemani. “Like the credit freeze impacted growth and the economy in every possible aspect, credit opening up will also slowly improve growth and the economic outlook, over a period of time.”

Others, however, say the property sector in particular needs further aid.

“The government needs to take further measures .... to improve the sentiments", says Shishir Baijal, the chairman and managing director of property consultancy Knight Frank India. “While, stressed a asset fund for [stalled] real estate projects has been rolled out, quick and effective implementation would be critical.”

Surendra Hiranandani, the chairman and managing director of Indian property developer, House of Hiranandani, agrees.

“There is an urgent need to address the challenge of liquidity faced by the sector, especially after the NBFC crisis,” she says. “If the challenge is not dealt with on priority, it will dent the confidence of developers as well as the buyers.”

Saturday's budget will be the ideal opportunity for the government to put concrete plans in action, analysts and business leaders say.

Mr Mishra is optimistic that a wide range of measures will be announced that will have a positive knock-on effect on easing the credit crisis.

“We expect the government will announce several measures to revive growth, which will be led by higher spending in key social sectors like infrastructure, roads and power,” he says. “This would create more employment opportunities leading to higher consumption and thereby a revival in the credit cycle.”

There's no doubt India's business community will be glued to TV screens, closely watching what New Delhi announces in terms of additional packages to help the situation.

“The government needs to act as soon as possible because if left unchecked [the credit crisis] will worsen the situation,” Mr Mishra says. “We believe they will try to address these issues in the upcoming Budget.”