Thomas Pink, the go-to shirt maker for slick City-types in London’s financial district from the 1980s to the early 2000s, has gone into retail hibernation in recent months, promising to return soon.

The brand closed its flagship store on Jermyn Street in August after never recovering from the first Covid-19 lockdown, before quietly shutting its other outlets late last year, closely followed by its social media channels and website in January.

Log on to its home page and a notification tells you the brand is returning “to its roots with the same team that has helped build Thomas Pink Shirtmakers over the years”.

It is the clearest signal yet that French luxury company LVMH, which paid £43 million ($59.88m) for 70 per cent of the company in 1999, is set to sell the British fashion house amid reports that a number of investors are already interested.

LVMH declined to comment on the sale.

“We have some things to iron out and button up but will be back soon with an improved website to offer you the highest quality English shirting made for modern life that you have come to know and love,” Thomas Pink’s website states.

Founded in 1984 by three Irish brothers – James, Peter and John Mullen – Pink became a City staple as financiers snapped up its brightly coloured shirts that offered the perfect price point between high street and London’s tailoring shops on Savile Row.

While high-flying bankers still favoured the more expensive suits Savile Row tailors dish out for thousands of pounds, there was growing demand from more modestly salaried professionals for the mid-market options supplied by Thomas Pink and its rivals Moss Bros and TM Lewin.

Former investment banker turned shirt maker Richard Bayley, 61, remembers the days well. While his preference in the 1980s was for TM Lewin’s £20 shirts, he migrated onto the higher-end Thomas Pink shirts in the 1990s, wearing them until he quit the City in 2007.

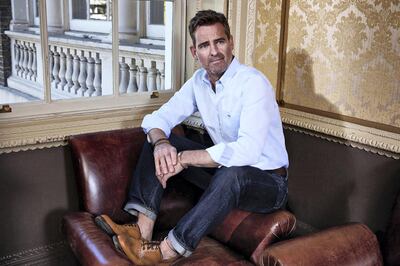

Mr Bayley, who set up shirt-making brand Fleet London in the fourth quarter of 2019, says he bought from Thomas Pink as recently as 2018 and used the company as a blueprint for his own brand.

“When we were setting up, Thomas Pink and Hackett were our two benchmarks in terms of the combination of quality and informality in some of the casual shirts,” he says.

“But we were aiming for a lower price point, because the higher the price you go to, the fewer sales there are.”

Fleet London focuses on two products, £70 shirts with a breast pocket and button collar and £25 slimline men’s underwear – both made from lightweight, sustainable cotton.

With most of the company’s operations taking place since Covid-19 started, Mr Bayley has relied on online sales and pop-up shops during lockdown-free periods to keep the brand on track.

“Several things hurt Thomas Pink in the last few years but Covid meant people are simply not buying small office shirts. That market has almost completely ground to a halt,” he says.

Shirt maker TM Lewin was another casualty of the crisis, closing 66 UK shops in July and laying off 700 workers as it took the brand online to cut costs.

While TM Lewin’s strategy since the City heyday of the ’80s and ’90s has focused on price – keeping its shirts consistently at the £20 mark and offering customers never-ending deals – Thomas Pink remained at the higher price point, charging about £125 to £140 for its shirts.

After LVMH bought into the company in 1999, the brand adapted well to online retail and consistently posted profits in the early 2010s, even after the global financial crisis.

Cracks began to show in 2017 when the brand experienced a high turnover in staff. It underwent a comprehensive rebranding in 2019, changing its name to Thomas Pink Shirtmakers.

Even having its factory based in Vauxhall, London, with everything handmade on site, was not enough to save the ailing brand.

“A high staff turnover is often a sign of internal troubles in a company. Whether it was a function of office politics or the balance sheet going wrong, I couldn’t tell you,” says Mr Bayley.

“The decline in demand for office shirts, which Covid has accelerated, pushed them over the edge but it sounds like there were some other problems in the company separate to any trends in retail.”

Kristian Robson, founder and managing director of Chelsea-based Oliver Brown, which offers ready-to-wear collections and bespoke tailoring, says Thomas Pink suffered from the same issue as many retailers of its era: "it expanded fast and probably overstretched itself".

“It had a lot of retail space and, no doubt, huge rental costs but did not appear to have a massive online presence,” he says.

“No one could have predicted the pandemic and any company that was retail-heavy will have been hit hard. There were a lot of shirt businesses and those who haven’t survived did not adapt to grow and develop their online offering.”

Mr Robson is aware of up to five large Jermyn Street shops that recently closed their doors, with many now looking to take their businesses online.

“With shops forced to shut, there have been a lot of layoffs at well-known Savile Row or Jermyn Street houses. There have also been shop closures as property costs have been crippling for businesses that didn’t have a good online business in place and those that might have been struggling pre-lockdown have been forced to close and rethink their business model.”

For many formal wear brands, the effects of Covid have been disastrous, as the nation's workforce switched to working from home, in turn ditching their smart wardrobes for casual wear.

"No one is going to the office and hardly anyone is wearing formal shirts, so formal shirts sales in the last year are probably at 25 per cent of where they usually are," says William Coe, the owner of Coes, a chain of six fashion shops in East Anglia.

While Thomas Pink’s Jermyn Street store opened for a few weeks in June, after closing during England’s first lockdown, it closed again within two months, with its other outlets following shortly after.

“If you are faced with a market that is literally shut down for a period, then going into hibernation does not sound like a bad thing to do,” says Mr Coe. “Not only are people not going to work, but they are also not going to any events, so Pink has been hit with a double whammy. Will that market come back? Yes, I think it will,” he says.

“Will it come back to the same level that it was before? I’m not sure that it will and I see a shift towards more casual attire. That is why Thomas Pink is trying to reinvent itself.”

Mr Coe switched strategy at his own shop, adding more casual wear lines and reducing formal shirt lines as the pandemic took hold.

With Mr Coe not expecting City workers to fully return to offices before September, he expects demand for formal wear to remain low for some time. However, he held on to stock of shirts, which sell for £70 to £100, because of the bloodbath on Britain’s high street in recent months.

“Locally, in Ipswich, Debenhams is now shut, Topman has shut down and Burtons has also gone,” he says.

“The number of shops where you could go and pick up a suit or a shirt and a tie is diminishing. The market may be getting smaller but the ability to get a greater share of that market is growing.”

Mr Bayley says his Thomas Pink purchases in recent years have focused more on the brand’s casual wear offering – making a return to formal wear a challenge for the brand.

When the brand does return, he says it would be unwise to reopen its Jermyn Street store.

“The West End of London has been hit particularly badly because of the lack of high spending tourists,” he says.

“Mayfair has been a wasteland, economically speaking, for the whole of the year, including the times when lockdown was lifted, simply because there hasn’t been travel. So, I don’t think re-establishing an expensive flagship shop in Jermyn Street would be a priority.”

Daisy Knatchbull, founder of The Deck, the first women's tailoring business to open on Savile Row last September, says the street is far from its "usual buzzy self".

“The absence of tourists is very palpable, making it a struggle for all tailors,” she says.

However, she insists the street’s global reputation as home to some of the best artisans in the world “will still be in demand post pandemic”.

For this reason, Mr Bayley says focusing on the bespoke upmarket route – on expensive but casual shirts – on a smaller scale “would be a valid strategy” for Thomas Pink going forward, particularly when office workers return along with an expected boom in formal wear.

While Mr Robson has relied on online appointments for Oliver Brown’s bespoke suit customers during the pandemic, he also says there is no loss in appetite.

“Our customers are professionals, many work in the city and they will be returning to work in offices once the lockdown has been lifted,” he says.