Little over a year since becoming UK Finance Minister, Rishi Sunak will on Wednesday deliver a budget that could make or break Britain’s economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

With 20 per cent of the UK workforce furloughed, youth unemployment soaring and nearly half of the businesses temporarily closed facing cash reserve crises, the challenges are manifold.

Mr Sunak faces a seemingly intractable dilemma: balancing Covid-19 support measures with the age-old political obsession of balancing the books.

The astronomical level of public sector borrowing over the past year would be enough to give most finance ministers restless nights, let alone a fiscally-orthodox Conservative who sees high levels of public debt as a cardinal sin.

Unparalleled measures, such as the £70 billion ($97.45bn) furlough scheme, self-employed grants and business loans propelled UK public sector borrowing to a record high in 2020.

Britain’s financial watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, forecast that for the 2020/21 financial year the total figure will near the £400bn mark.

Sunak urged to splash the cash in budget

Despite the giddy sums involved, the consensus among macroeconomists is that now is not the time to turn off the taps.

The Institute for Public Policy Research called for the government to ignore the siren call of debt reduction and instead focus “on delivering the spending necessary to secure a recovery from Covid-19”.

It cited modelling that suggests public debt as a proportion of GDP could fall if the level of investment was sufficiently high, a prediction backed by the IMF.

With interest rates charged on government bonds at record lows – the 30-year gilt is currently at 0.88 per cent – the IPPR said the UK is set to spend less on servicing the debt over the coming years than previously forecast.

Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane compared the potential for stimulus-induced inflation to a "tiger" on the prowl. Yet, with the current figure at 0.7 per cent, there appears little danger of the tiger baring its teeth.

What Sunak will include in his budget

With Mr Sunak opting for tax increases rather than unbridled borrowing, the three areas of focus are likely to be corporation tax, pension tax and capital gains tax.

He is considering increasing corporation tax from 19 per cent to 20 or 21 per cent, with each percentage point rise adding £3bn to the UK ledger. He is also considering restricting the amount people can put into their pensions over their lifetimes to £1 million, which would save £250m in tax relief.

"It pains me to say, after spending much of my life arguing for lower taxes, that we have reached the point where at least some business and personal taxes have to go up," he wrote in The Telegraph on Tuesday.

The overarching goal is simple: economic growth.

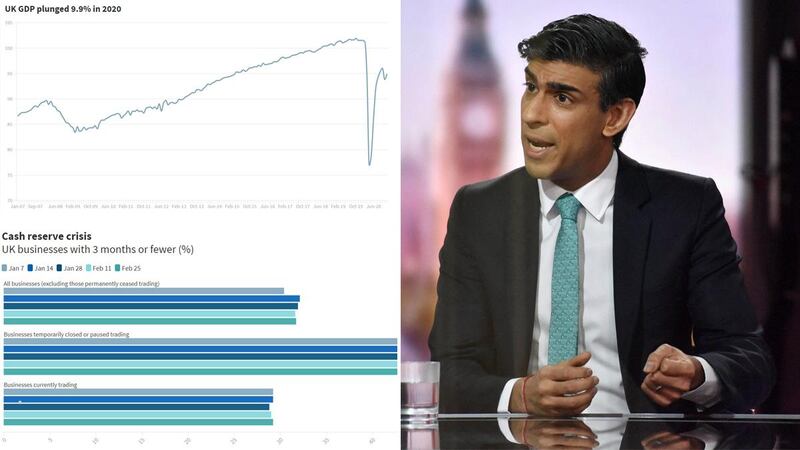

The value of everything the UK economy produced in 2020 (gross domestic product) was down 9.9 per cent compared to 2019. This marked the greatest slump in UK growth since the Great Frost of 1709, a year so frigid frozen birds reportedly fell from the sky.

A more recent comparison is the 2008-9 financial crisis, which the Covid-19 plunge has eclipsed.

If the economy is to rebound to its giddy pre-Covid heights, then Mr Sunak will have to continue to support businesses.

Sobering data from the Office for National Statistics show that as of February 25, approximately 50 per cent of temporarily closed businesses have fewer than three months of cash reserves left.

Many of these businesses are in hospitality, arts, leisure and retail.

Illustrating the malaise, ONS data show that 60 per cent of accommodation and food service businesses had paused trading in mid-February.

It is anticipated that Mr Sunak will extend the 100 per cent tax cut he implemented in these ailing sectors last year. Its continuation could be subsidised, at least in part, through the £2bn of unused tax relief rebated by larger firms last year.

The temporary reduction from 20 per cent to 5 per cent in VAT for the hospitality and tourism sectors is also likely to be extended for at least another three months, and he is planning to hand out £408 million to help museums, theatres and galleries in England reopen.

Will there be a 'Shop Out to Help Out' scheme?

Tax relief and one-off handouts will struggle to cut the mustard, however.

British retailers suffered their worst annual performance on record in 2020, despite a boom in e-commerce.

Retail sales were down 8.8 per cent in January 2021 from December 2020, and Mr Sunak is said to be considering a ‘Shop Out to Help Out’ scheme in the vein of its gastronomic forebear.

A voucher scheme for shops isn’t high on the finance minister’s agenda, however. Sales have been shown to pick up fairly rapidly in the months when restrictions are loosened.

What data doesn’t show is how the spend is spread across socioeconomic groups in the UK. It is unlikely that much of it will have stemmed from the 1.74 million employees who were without a job as of December last year.

This represented a 454,000 rise from December 2019 and led to vociferous cross-party calls for an extension to the £20 universal credit top-up that is due to expire in April.

Mr Sunak is renowned as an operator who keeps a beady eye on the optics, as the video below shows, and it is likely that he will heed the clamour and extend the uplift by another six months.

Rishi Sunak stars in cinematic video ahead of Budget 2021

What measures for jobless young people in Sunak’s budget?

Figures based on tax data show a 726,000 fall in the number of employees on business payrolls since February 2020, with under 25s accounting for 425,000 of these.

If he decides to tailor support along age lines, then those between 16 and 24 will be among the beneficiaries with money made available for job support, retraining, apprenticeship and a mortgage guarantee scheme that aims to help first-time buyers get a foot on the property ladder.

The great fear is that the unemployment rate has been kept artificially low by the furlough scheme, Britain’s most expensive Covid support measure. If it expires on April 30, it will have cost an estimated £70bn.

Mr Sunak will be hoping that as restrictions are eased, the burden on the scheme will ease too – but the trend is going in the opposite direction.

Twenty per cent of the UK workforce is on furlough, almost double the 11 per cent in early December 2020 before England was pitched into its third lockdown.

While the proportion of the furloughed workforce in June 2020 was at 30 per cent, it is a figure that remains uncomfortably high – and increased even further in the last two weeks of February.

Mr Sunak said he will use the budget to set out the next stage of his Plan for Jobs to be provided “through the remainder of the pandemic and our recovery”.

The glaring hole in the assertion is that the pandemic has shown little interest to date in having a cut-off point, regardless of political rhetoric to the contrary.

The non-Covid measures in Sunak’s budget

Another crisis showing little prospect of ending is climate change.

If Covid were not so all-consuming, in the year when COP-26 will be hosted by the UK in Glasgow, green measures might have been expected to dominate the budget.

Instead they will be playing a very distant second fiddle – especially in the wake of the green homes grant being pared back in January in an attempt to save money.

Expect just a few nods to sustainability, one being the expansion of the electric vehicle-charging network.

The funding of three green programmes through the government's £1 billion ($1.39bn) Net Zero Innovation Portfolio is also on the cards, as is £20m ($29m) to develop offshore wind demonstration projects.

There will also be an acceleration of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s much-fabled 'levelling-up' agenda, with more investment in transport, infrastructure and town centre regeneration.

Counter-cyclically, British house prices soared 8.5 per cent in 2020 to an average record high of £252,000 – a trend sustained in February 2021 – as the market benefited from a temporary tax break and pandemic-induced demand for more space.

Fuelled by its success, Mr Sunak is expected to use the budget to move the tax break to June 30 to bolster the market further.