The Middle East has a rich trading history. In the the 3rd century BC, for instance, the Incense Route - a network of trade routes extending more than 2,000 kilometres to facilitate the transport of frankincense and myrrh from Yemen and Oman in the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean - was one of the major arteries of world trade. Around the same time, Gerrha - believed to be in modern-day Saudi Arabia or perhaps Bahrain - was an important trading centre.

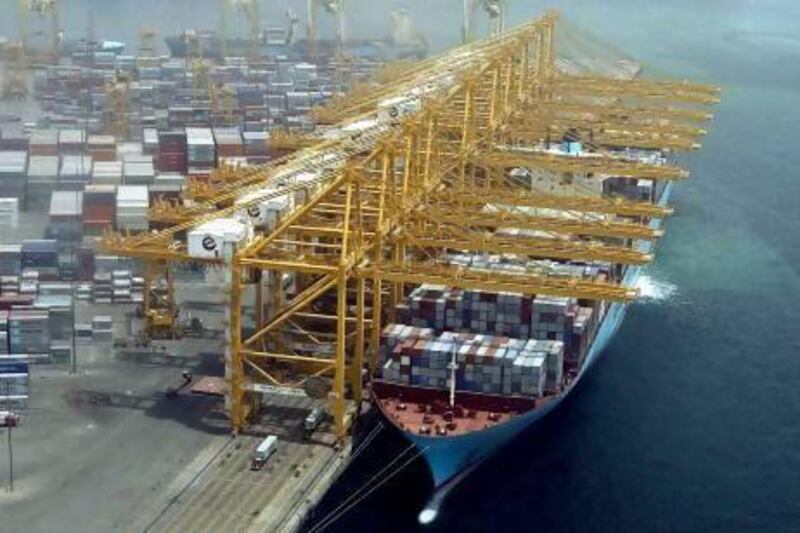

More recently, trade has been one of the main engines of growth for the UAE economy. In the decade to 2011, the UAE's trade, as measured by total imports and exports, increased more than five-fold from less than US$100 billion (Dh367.27bn) to $550 bn. Relative to the size of its economy, trade reached 156 per cent of GDP - the cash value of money spent on goods and services. And contrary to what one might expect, oil accounts for only 20 per cent of this trade - testimony to the country's economic diversification.

Not surprisingly then, the UAE ranks 19 (out of 132 countries) - ahead of the United States, France and Ireland - on the World Economic Form's Enabling Trade Index, which measures a country's institutions, policies and services that facilitate the free flow of goods over borders and to their destinations.

On a similar index published by the World Bank, the Logistics Performance Index, the UAE ranks 17 out of 155 countries.

Today, however, two fundamental changes are under way.

First, the world trade growth is slowing down. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), world trade growth fell to 2 per cent last year - down from 5.2 per cent in 2011 - and is expected to remain sluggish this year at about 3.3 per cent as the economic slowdown in Europe continues to suppress global import demand.

The projected trade growth for this year is below the 20-year average of 5.3 per cent and well below the pre-crisis trend of 6 per cent during 1990-2008. The story for the UAE is no different. According to the figures published by the WTO, the UAE's trade growth was about 6 per cent last year, down from an impressive 26 per cent growth in 2011.

Second, competition within the Middle East is increasing. Location-specific advantage is not unique to the UAE. Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait and Qatar are also pressing ahead with ambitious developments of clusters of special economic zones, (SEZs) and logistics hubs. Saudi Arabia has the added advantage of a strong, large domestic market.

Oman has easier access to India, China and the African continent while avoiding the sensitive Strait of Hormuz. Witness the transformation of Duqm - 450 kilometres south of Muscat - from a fishing village to an aspiring SEZ and trading hub: a dry dock has been built and a special economic zone, with industrial area, new township, fishing harbour, tourist zone, and logistics centre is planned. Both the countries have made significant progress in terms of their Enabling Trade Index rank: Saudi Arabia from 40 (2010) to 27 last year and Oman from 29 (2010) to 25 (2012).

The UAE's success in positioning itself as the trade hub of the region was thanks to its pioneering efforts, which gave it the first-mover's advantage. Trading hubs and SEZs have a long incubation period. Even the biggest SEZ success stories such as China and Malaysia started slowly and took at least five to 10 years before they began to build momentum. So in the short-term, the UAE's position is not likely to be challenged.

Sustaining competitive advantage, nonetheless, requires going beyond world-class infrastructure and business environment, which, according to a recent World Bank report, is the starting point.

The report cites useful lessons from successful SEZs: first, reforms of the domestic investment climate are equally important. After testing business reforms in the SEZs, the Chinese government launched nationwide reforms, the result of which is one of the biggest economic miracles in the recent past.

Second, government's role should evolve from providing infrastructure, employment and cost advantage to building technology infrastructure and protecting intellectual property rights - as demonstrated in the "miracle of Shenzhen", a fishing village transformed into a cosmopolitan city of more than 14 million, with per capita output growing 100-fold, in the 30 years since it was designated as an SEZ.

Equally important is facilitating backward linkages - getting firms to source resources locally brings enormous economic benefits. Facilitated by government encouragement, added domestic value in Masan Zone, a highly successful South Korean SEZ, increased from 28 per cent in 1971 to 52 per cent in 1979.

Dynamic and successful SEZs have many more lessons to offer. Ultimately, adopting and adapting these lessons will be the key for GCC SEZs to remain competitive.

Amit Tyagi is a vice president in the risk management division of the National Bank of Abu Dhabi