Giza’s pyramids were built by appropriating Egyptian labour: they represented a transfer of wealth, time and income from the kingdom’s slaves to the government of Pharaoh Khufu.

But their exact overall contribution to the economy of the Old Kingdom of Egypt is unclear.

This is not because monuments are of dubious economic value – the tourism revenue alone makes Khufu’s construction plans look visionary.

The problem is that slaves subsidise their masters – their welfare and labour power are traded for their masters’ output.

Not everything that their masters produce, therefore, is new output. Much of it represents a transfer of income, and not an increase in overall income.

Had the slaves not been working to build an Ozymandian comment on hubris and mortality, they might have been fishing or farming or crafting pots – the mainstays of the pre-Modern Egyptian economy.

This is one of the earliest examples of the economic concept of crowding out.

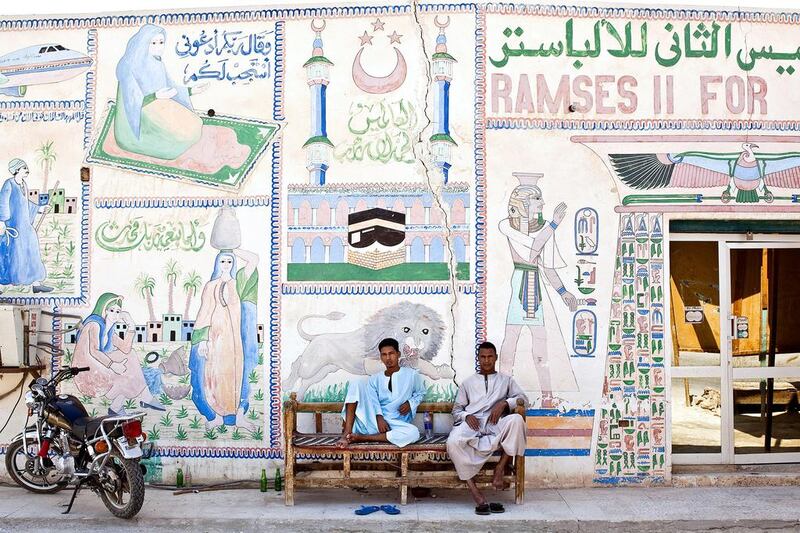

In today’s Egypt, a decade of fiscal deficits has limited the ability of public megaprojects to power growth. The government has crowded out private investment. Egypt’s leaders now have no choice but to look to foreign companies for capital to fuel economic growth.

When governments transfer output and income to themselves, the result is a redistribution of welfare, not an increase in economic dynamism. The domestic buying of government debt reduces national savings, and private-sector investment falls along with it.

In today’s internationalised economy, this does not need to happen.

Modern governments can issue debt for foreign investors to buy. This increases the spending power of governments while reducing the buying power of foreign investors.

Fortunately for the government’s accountants, debt purchases by foreigners do not reduce domestic spending or investment.

And fortunately for Egypt’s citizens, it is easier to tap bond markets than it is to round up forced labour.

If foreign investors were financing the government, this would not harm growth, but the main buyers of Egyptian sovereign debt are Egyptian retail banks. The country’s deposits are being used to finance the government’s spending gap – not to help SMEs grow.

This limits the availability of credit to the private sector and pushes up interest rates on domestic loans.

Finance experts call banks that prefer to park their money in domestic sovereign debt “lazy”.

Samah Shetta, Ahmed Kamaly and Mona Fayed, economists at the American University of Cairo, have tested whether Egypt’s bankers meet this definition. Their conclusion is that local banks prefer to hold on to Egyptian debt, and that this deprives the private sector of new loans.

Egyptian debt issuance causes banks to “shift their portfolio away from risky private loans and opt for lazy behaviour characterised by a shrinking overall credit tilted more and more towards government debt-instruments,” Ms Shetta and Mr Kamaly write.

“This [reduces] private investment, [and] adversely affects investment and hence overall growth potential,” they say.

Academics at Georgetown University found that the problem of lazy banks is pervasive across the developing world. In a study of 60 developing economies, they argue that every US$1 placed by the government at domestic banks reduces private credit by $1.40.

“Access to safe government assets … may create moral hazard and thus discourage the banks from lending to the risky private sector,” write Subika Farazi and Shahe Emran – a situation where banks are insulated from the risk involved in sovereign debt issuance.

Loans made by Egyptian banks to the government grew by an average of 77 per cent over the past three years, while loans to the private sector grew by 5 per cent over the same period.

Just as in millennia past, Egypt’s government is crowding out private economic activity.

This is why foreign investment and Arabian Gulf aid are crucial.

The good news is that “there is a lot of foreign interest in Egypt,” says Jason Tuvey, an emerging markets economist at Capital Economics.

“Low wages, a young and growing workforce, and proximity to development markets in western Europe” mean that the country has “enormous potential to become a manufacturing hub”, Mr Tuvey says.

New injections of capital from foreign energy giants announced at Egypt the Future, the investment conference in Sharm El Sheikh, will be a relief for a government that has had difficulty paying its energy bills. The Egyptian government owes energy firms $3.1 billion in missed payments, which it expects to pay back in late 2016.

Siemens, BP, Eni, Masdar, General Electric and the Saudi firm Acwa announced about $36bn of investment in Egypt’s energy sector in separate projects.

It is new private investment, not government mega-projects after the fashion of the pyramids, that will help Egypt grow.

abouyamourn@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter