The main three reasons why international oil companies (IOCs) are interested in partnerships with oil-rich countries are reserves, reserves and reserves.

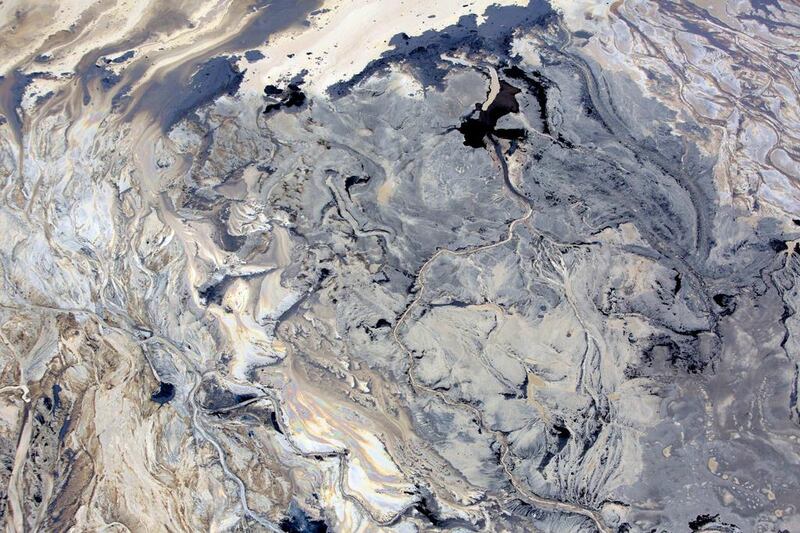

This is no secret or wonder, as IOCs control less than 10 per cent of the world’s reserves and scour the globe in the hopes of booking reserves to push up their reserves replacement ratio (RRR). According to a recent report produced jointly by Oil Change International, Greenpeace and Platform, at least four of the largest six IOCs are dependent on the expensive and hard-to-process tar sands reserves to boost RRR rates. Tar sands account for up to 71 per cent of their total liquids additions.

This is why Mexico’s recent announcement to change the constitution to allow outside participation in the oil industry and the possibility to book reserves has been welcomed with joy by IOCs.

On the other hand, the state's choice of oil partners, whether IOCs or international national oil companies (INOCs), is not straightforward. For oil-rich governments, the capability of oil partners to manage and share risk is a major factor that can tip the pendulum in favour of one partner against another.

Today, the size and scope of states’ national oil companies (NOCs) rival those of any IOC. NOCs’ oil partner options, whether through production-sharing, profit-sharing or concession contracts, are almost unlimited. NOCs’ access to and use of capital markets to finance projects have improved considerably.

Moreover, the development of oil trading markets has eliminated the risk of market availability. More importantly, the vast majority of the world’s oil reserves are in the hands of NOCs. This situation has caused a major change in the industry’s power structure – NOCs have the upper hand in oil deals with IOCs.

In its partnerships with oil companies, the state looks for benefits that go beyond the mere task of exploring for oil and finding markets for it. It looks for opportunities to do business with partners that can help it to obtain technology, develop unconventional reserves, train the local workforce and enhance the country's economic performance.

Many view oil partnerships through the prism of risk, the magnitude of risk involved in exploring and developing reserves and the state’s capability to take that risk. The state with a capable NOC does not need to partner with IOCs to develop proven and mature oil reservoirs where the geology is certain and development risks are low.

These low-risk reserves are cash cows used as incentives to attract capable oil partners to jointly develop frontier resources that are technologically and geologically riskier. A considerable amount of weight is given to partners’ ability to unlock the full potential of the country’s oil and gas reserves.

According to some estimates, unconventional reserves – such as heavy oil, shale oil and gas, and tight oil – represent about two thirds of the world’s total reserves and only 5 per cent of the current production. However, it is expected that the production from unconventional reserves will reach about 13 per cent by 2035. Clearly, companies with innovative technologies have a competitive advantage in negotiating oil partnerships with host governments with ambitions to develop their untapped unconventional reserves.

Additionally, in their negotiation with potential oil partners, the resource-rich governments factor in the ageing fields where primary and secondary recovery methods such as gas and water injection are becoming less effective. These declining fields require tertiary recovery methods such as carbon dioxide injection, technology that many host governments have not mastered or obtained yet.

Many states look for partners that can offer a package of benefits not restricted only to one area of the hydrocarbons industry – those that put forward offers that add value through the entire industry value chain, from reserves exploration and development to refinery construction and operation.

Since most major NOCs and IOCs are vertically integrated, a partnership contract in one part of the industry could offer business opportunities in other parts. This integrated approach has been seen in the region where NOCs and IOCs agree to jointly develop reserves and jointly build exporting and distribution facilities. This way oil-rich governments offer exploration blocks and receive access to markets in return.

The challenge for IOCs is to be able to listen and respond to the host government’s aspirations for the hydrocarbons industry and the country as a whole. They should also demonstrate their ability to add value, provide technical expertise and transfer technology – not only on paper, but more importantly on the ground. It is also the responsibility of the state to ensure that it takes full of advantage of its agreement terms and that the IOCs deliver on their promises.

The state can use previous experiences to assess the ability of potential partners to deliver. This is particularly true when long-term oil contracts are due to end and there is a possibility to choose between old and new partners.

The aforementioned are factors considered by rational states making rational decisions. However, there are those that choose to make oil partnerships based entirely on politics, to the detriment of their economy and people.

Ebrahim Hashem is a senior adviser in business strategy and corporate governance at an Abu Dhabi-based company. Contact him via twitter @EbrahimHashem