It is tempting to think the spirit of "change" - the leitmotif of Barak Obama's successful presidential campaign - will infect the world's ruling elite as they meet in Washington on Saturday to hatch ways of reviving a stricken global economy. The stakes couldn't be higher, and as if to swell expectations, it is billed as a follow-up to the 1944 Bretton Woods meeting, where leaders of the allied nations hammered out the world's post-war economic architecture. Should Bretton Wood II end with a fizzle, as many economists fear, investors will do to markets worldwide what American voters did last week to the Republican Party.

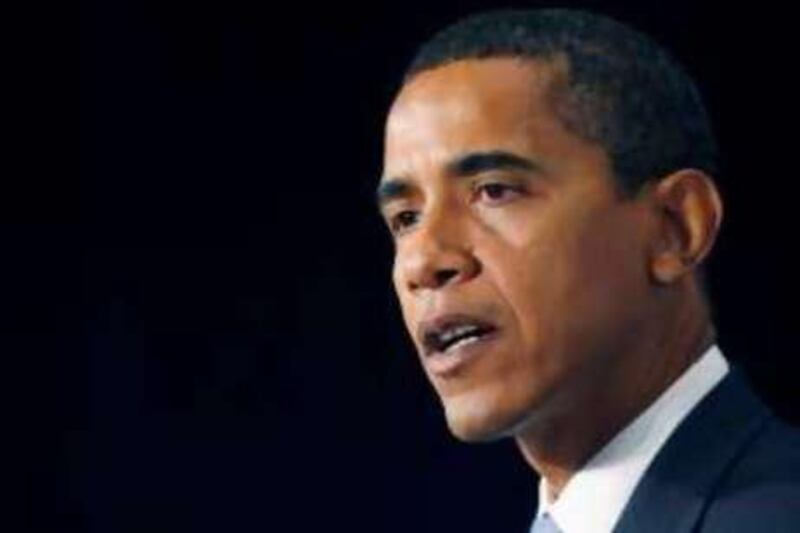

Sadly, the contrast between Mr Obama and his campaign team - bright, innovative, deliberate, fearless - and the summit's attendees couldn't be more stark. French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who has pushed for the 20-nation gathering, is unpopular at home, while British prime minister Gordon Brown and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are on the defensive. Despite this, they are promoting, in varying degrees, an aggressive regulatory agenda.

Mr Sarkozy supports a new agency that will monitor transnational banks and capital flows, laws to inhibit tax havens, and greater transparency for hedge funds. He even wants to structure the salaries of financial traders in ways that would reward the risk-averse. Mr Brown and Ms Merkel, for their part, are counselling similar, if less intrusive reforms. The lame-duck President Bush, meanwhile, has expressed only token support for the summit, pregnant as it is with "world government" connotations inimical to his go-it-alone conceit. He has called airily for a series of informal gatherings while cautioning through a spokesman against "moving too far too fast ? to avoid unintended consequences." That's easy for him to say, only weeks away from retirement on a comfortable pension.

It's hard to see what good can come of all this, particularly when no one seems to be telling the markets what they want to hear - namely an assurance that the International Monetary Fund, the lender of last resort to fallen economies, is sufficiently cashed up. Currently, the IMF has US$260 billion (Dh954.2bn) available, a drop in the bailout bucket given the parlous state of the developing world. Clearly, IMF resources must be expanded, and fast.

The problem, ironically, is with those same European leaders who are so eager to impose new regulations on a frail global economy. It was Bretton Woods that sired the IMF (alongside The World Bank, which unlike its Eurocentric counterpart is traditionally chaired by an American), with the straightforward mission of rebuilding war-torn Europe. Since then, its membership has quadrupled in size, though its shareholding structure hasn't been recalibrated since 1998, when the economy was half as large as it is today.

As a result, European Union members collectively enjoy a disproportionately large voting bloc through the agency's limited distribution of quota, or shares - 27 versus America's 17 and Japan's 6. By reallocating new quota, the fund could raise more money - a 50 per cent increase could yield between $100bn and $155bn, according to Edwin Truman, a fellow at the Washington-based Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics. That would come largely at the expense of its European shareholders, however, who have resisted an expansion of quota beyond the 12 per cent it allowed in January.

Until recently, the IMF appeared to be heading for oblivion. The bailout packages it arranged during the regional financial crises of the late 1990s had been paid off and the global economy, or so the optimists proclaimed, had somehow evolved out of the boom-bust cycle. (Remember the end of inflation?) Now, the IMF is once again in great demand. In the last several weeks it has approved rescue programmes for Iceland, Ukraine, Hungary, and Pakistan.

No doubt more such bailouts will be needed before the global economy bottoms out, and unless the fund's European overlords give way on the need for quota adjustment, it may not be up to the task. (Mr Truman estimates the IMF will need a war-chest of $1 trillion to get through the crisis.) While Europe's leaders are unlikely to accept a drastic diminution of their shares to make room for greater influence for a cash-rich Asia, as some have suggested, their silence on the matter suggests an ostrichlike capacity for denial.

Last week, American voters were given the chance to reject the politics of nativism, partisanship, and paralysis. To use an American colloquy, they stepped up to the plate and they knocked it out of park. Hopefully, Europe's leaders will remember their example on Saturday, if nothing else to show that there is no American monopoly on change. sglain@thenational.ae