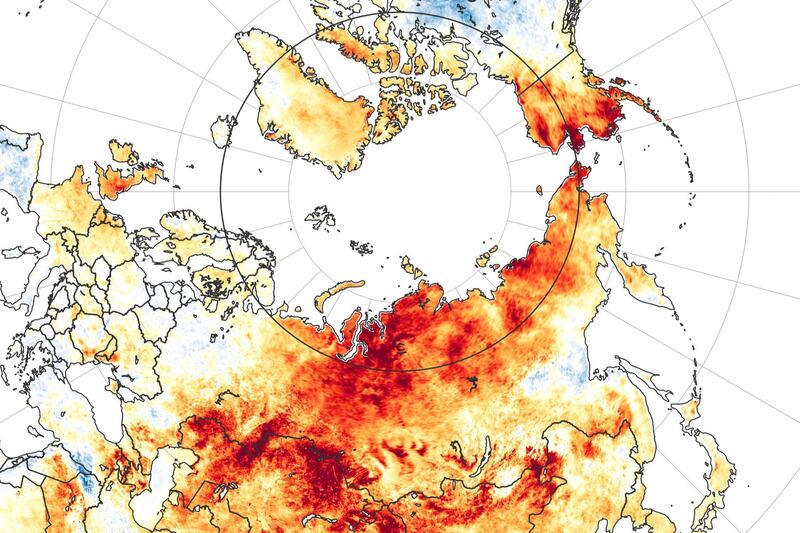

In Dubai on Friday, the temperature reached 40 Celsius, nothing surprising for this time of year. Yet Verkhoyansk in Siberia, north of the Arctic Circle, hit 38 degrees, an Arctic record. This shocking occurrence, in one of the coldest places in the world during winter at -50 degrees, warns the petroleum industry that rapid, transformational and disruptive change is imminent.

An increasing number of oil companies, including Shell, BP, Total, Eni and Repsol, have announced goals to be net zero-carbon by around mid-century. It might seem a radical departure for Opec to emulate them – but in some ways, it would be returning to the roots of the petroleum exporters’ organisation.

Italian historian Giuliano Garavini, in his history of Opec which I reviewed here in January, argued that Opec had antecedents as a conservation organisation. The Texas Railroad Commission's petroleum regulations, an inspiration for Opec, were born out of the wish to curtail physical waste of oil in the early 1930s glut.

Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, former Venezuelan oil minister and one of the early guiding spirits of Opec, and the deposed Shah of Iran’s finance minister, Jamshid Amouzegar, were both conservationists.

The organisation went through several incarnations following its foundation in 1960. At first, it secured its members a fair share of their oil revenues by coordinating on taxation and forming a common front against the international oil firms who then dominated the industry. Then in the 1970s, it was the agent of increasing prices and nationalisation.

Only in the 1980s did it take on its familiar modern role, of propping up falling prices by setting per-member limits on production. Most recently, from 2016 onwards, it has widened this scope by cooperated closely within the Opec+ framework including Russia, Oman and other petroleum-exporting states.

Individual national oil companies (NOCs) of Opec+ countries have, of course, been preparing themselves for a lower-carbon future and the rise of electric vehicles.

Adnoc and Aramco have large-scale plans for carbon capture and storage. Aramco is developing mobile carbon capture systems and substitutes for metallic materials made from oil. Petroleum Development Oman is rebranding as Energy Development Oman and investing in renewable energy projects. Expansion into petrochemicals instead of transport fuels is de rigeur for many NOCs.

Some other state oil giants within Opec+ are struggling just to run their businesses in the face of the collapse in prices, the disruptions of coronavirus, and sometimes local conflicts and political turmoil. They do not have the opportunity or ability to take the slightly longer view.

So, what would Opec do, if recast as an organisation to guide its members through the climate crisis? One of its current core intentions would remain: coordinating production to achieve relatively stable and attractive prices and dealing with unexpected upsets in the world market.

Beyond this are three key duties it could take on. The first is to develop a long-term, climate-compatible view of the demand for oil, and help guide individual members in updating their plans for their oil industry and national economy in that light.

The second is to coordinate an Opec response on global climate policy. The organisation has often been seen as a barrier to climate action, even if that was more to do with the position of some individual members. Instead, it needs to maximise the value of its remaining hydrocarbons while charting a path to net zero. That includes policies to tax carbon rationally and efficiently, offset emissions by drawing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, develop non-emitting uses of oil, and adopt domestic regulations to avoid carbon border tariffs such as those proposed by the EU.

The third is to progress an ambitious technology development programme. The Opec Fund for International Development has total assets of $7.3 billion (Dh26.8bn), and has financed various climate-related initiatives. For the sake of its members, the organisation should be partnering with international oil companies and governments to advance research and development in key but underfunded areas.

These include ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, including biosequestration, mineralisation and the creation of ceramics, fuels and plastics. Cooperation with Japan, Australia and Germany on generating, transporting and using carbon-neutral hydrogen is promising. Geoengineering may be necessary to cool the Earth directly.

Would it better for Opec, or the wider Opec+ grouping, to take on these tasks? Opec+ is not yet a formalised organisation and may never be. It is also more heterogenous, including a wider range of geographies than Opec’s primarily Middle East-Africa membership. Some non-Opec members are large gas exporters, some have quite diversified economies, and most have smaller oil reserves, declining production and less strategic flexibility.

Most importantly, Opec+ includes one large and influential state. Russia has lagged on taking climate change seriously. Its big government companies, Rosneft and Gazprom, have not shown urgency to reshape their business models.

Now, in the face of the heat and continuing wildfires in Siberia, and the massive oil spill earlier this month, blamed on melting permafrost, there are signs President Vladimir Putin may be paying more attention to global warming. Nevertheless, it would be hard to reconcile Moscow’s environmental imperatives with those of the main Opec states.

If Opec can manage this coordination, it would mark the next phase in its sixty-year existence. This return to its origins in the responsible use of nature’s bounty would also assure its future, and that of its members.

Robin M. Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis