Twenty years ago last week, US tanks rolled across the Iraqi border. And nearly to the day, Saudi Arabia and Iran signed a Chinese-mediated deal to restore diplomatic ties. During those two decades, America’s unipolar moment faded, it achieved its longed-for “energy dominance”, but that dominance is nowhere less apparent than in the Middle East.

The motivations for the 2003 American invasion have been deeply debated, and varied between proponents and depending on the audience. Unlike Saddam Hussein’s earlier seizure of Kuwait, it was not a “war for oil”.

Certainly, Iraq’s military and economic power depended on its petroleum, and it had earlier threatened to dominate the hydrocarbon-rich Arabian Gulf with its invasions of revolutionary Iran and then its smaller GCC neighbour. A stable, pro-American Baghdad might indeed help assure the US’s dominance over this critical area.

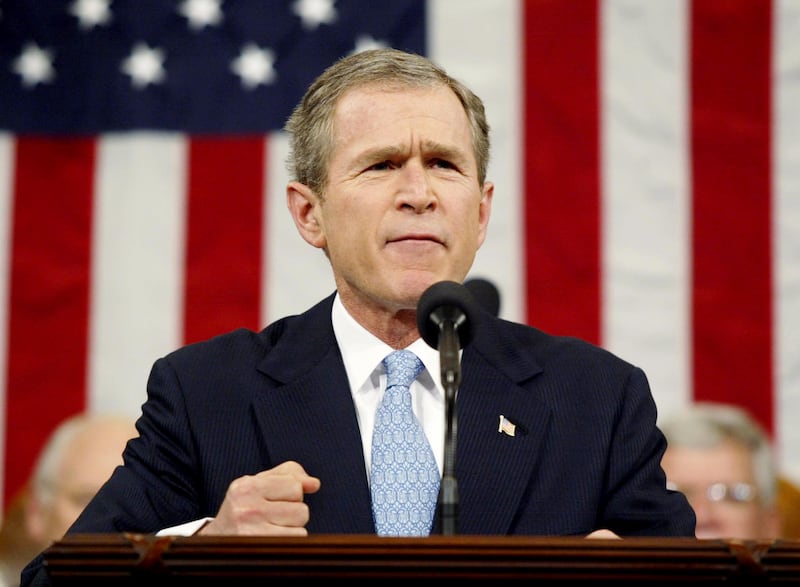

Various figures in the Bush administration had hopes that a post-invasion Iraq might be detached from Opec, that they could privatise its petroleum industry, or that a flood of new Iraqi oil might bring down oil prices, which then seemed uncomfortably high at around $30 per barrel.

Richard Perle, a leading neo-conservative advocate for the war and an influential defence official at the time, said in July 2002: “Iraq is a very wealthy country. Enormous oil reserves. They can finance, largely finance the reconstruction of their own country.”

The White House press secretary, secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld, deputy secretary of defence Paul Wolfowitz and others made similar comments.

But the US did not seize Iraqi oil for its own use or determine who should have access to it and who should be denied.

Indeed, ex-president Donald Trump repeatedly complained that the US should have done so, saying in 2011, “In the old days, when you had a war, to the victors belong the spoils. You go in. You win the war and you take it”, and repeating that theme numerous times in 2016, 2018 and, regarding Syrian oil, 2019.

Instead, the occupation authorities were remarkably lackadaisical about rebuilding the Iraqi petroleum industry, in the middle of an insurgency, a civil war and the takeover of the oil hub Basra by the Mahdi Army militia.

Two decades of war, sanctions and brain drain had devastated the sector. Outside the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region, Iraqi nationalism won out over American free-market ideology and there was no significant foreign investment. As late as 2010, output was below 2001 levels.

That failure contributed to the remarkable global oil price surge up to the middle of 2008, which was supercharged by China’s runaway economic growth.

When the 2008-2009 financial crisis caused prices to crash, the Iraqi government finally offered its major fields to international oil companies in competitive bids. The winners were a fairly balanced mix of Americans, Japanese, Europeans, Malaysians, South Koreans, Russians, Chinese and others.

Far from plundering Iraq’s resources as the western left alleged, these companies ended up with extremely harsh contracts that left them with just one or two dollars per barrel profit and low or negative returns on capital after shouldering long bureaucratic delays, late payments and lack of required infrastructure.

The last American corporation, ExxonMobil, is in a protracted process of withdrawal; Equinor (then Statoil), Occidental and Shell left the oil sector years ago, though Shell hangs on in gas. Russia’s Lukoil has repeatedly threatened to go. Chinese companies secured most of the spare stakes.

Last month, Baghdad finally signed six exploration and field development contracts that had been in limbo since its 2018 bid round; three went to Sharjah-based Crescent Petroleum and the other three to Chinese firms.

The Iraqis have grown concerned that China is too dominant in their oil business — Chinese service and engineering companies also play a big role, including operating the giant Majnoon field on the border with Iran, after Shell withdrew.

Nevertheless, they have not improved their terms enough to entice new entrants and the painful experience of France’s TotalEnergies in exhaustive negotiations for an oil, gas, power and water package deal will deter others.

Iran, now a major gas and electricity provider to Iraq, also plays an important, usually negative, behind-the-scenes role in the energy sector.

The Kurdistan region’s claim to an independent oil sector appeared as a relative success, but it emerged out of the hasty, messy constitutional compromises of 2005.

On Saturday, Turkey ceased pumping oil from Kurdistan through its territory, in deference to a Paris arbitral tribunal’s finding in favour of Baghdad. This is a potentially devastating blow to the generally western-aligned government in Erbil.

The US ended up playing the role it had hoped Iraq might. Its surge of shale oil production brought down prices sharply from 2014 and gave the Obama administration the confidence to impose stringent sanctions on Iran’s oil exports.

Opec realised it could not tackle both shale and Russia together. It brought Moscow into the Opec+ alliance in 2016.

The US has stepped up as a critical provider of oil and gas to Europe following Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

But Washington’s moment of “energy dominance” may have been fleeting, as its shale oil expansion runs out of steam.

President Biden visited Saudi Arabia in July hoping for more Opec output to compensate for losses from Russia.

Instead, the organisation consulted its own interests and cut output in November, apparently wisely given the recent sharp price drops.

American commentators from right to left welcomed the idea that shale would free the US from dependence on the Middle East.

But that goes both ways.

Now the largest importer from, and exporter to Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia, is Beijing, not Washington. Then China was able to mediate the restoration of Riyadh-Tehran relations.

If and when it wants, China will be able to call the shots in Baghdad too.

Robin M. Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis