Standing more than 2 metres tall, the Chinese basketball player Yao Ming is a towering presence, but not just physically.

Enormously popular in his home country, Yao, 31, has made a fortune from endorsements, snapping up contracts with Reebok, Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Visa.

Last year, Forbes reported Yao's connection with Reebok alone - he previously had a contract with rival Nike - netted him a cool US$10 million (Dh36.7m).

But what is extraordinary is that Yao made his name overseas, in the United States National Basketball Association (NBA) league, with the Houston Rockets, before retiring as a player last year.

Known as the Great Wall of China, his stunning success highlights the relative lack of exposure and commercial clout of the sporting scene in his own country, even though he paid 96m yuan (Dh55.4m) in 2009 to buy his hometown team, the Shanghai Sharks.

Although Yao is now focused locally, many Chinese leagues struggle to attract interest from fans and revenue from sponsors. Often they are regarded as being blighted by corruption.

"There's a perception that the [Chinese] leagues are not very well run," says James Roy, a senior analyst at China Market Research Group.

Corruption in Chinese soccer was highlighted this month when Nan Yong and Xie Yalong, former heads of the Chinese Football Association, were jailed for more than 10 years each for taking bribes.

With domestic professional sport tainted, foreign leagues such as the NBA and the English Premier League (EPL) generate the big endorsements in China. The footballers who achieve the greatest prominence in China and fill the billboards are from the EPL, Spain's La Liga or Italy's Serie A.

The EPL champions Manchester City and rivals Arsenal are big enough to play a friendly in Beijing's Bird's Nest stadium next month as part of what the British media have branded their "lucrative world tours".

Domestic teams, meanwhile, typically fail to fill smaller venues.

Matt Beyer, who runs the sports consultancy Altius Culture in Beijing, points out that the NBA has close to 30 official corporate partnerships specific to China.

"They're nearly all with Chinese companies. You have Lenovo [the second-biggest PC maker in the world behind Hewlett-Packard], you have car companies, different types of clothing, fast-moving consumer goods," he says.

The retired NBA player Shaquille O'Neal recently starred in a television advertisement for a Chinese drinks brand, and he is unlikely to have come cheap. In 2006, he signed a six-year deal with the Chinese sports clothing manufacturer Li-Ning for $6.2m.

A question often asked is whether the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) and football's Chinese Super League will narrow the gap with major international competitions, and attract the same sort of deals. Recent big-name signings have fuelled interest.

Aaron Brooks left the Houston Rockets to join the Guangdong Southern Tigers for a reported $2m pay packet, while Kenyon Martin was on a CBA record salary when he left the Denver Nuggets to join the Xinjiang Flying Tigers for $2.5m. Both have since returned to the NBA.

Stephon Marbury, a former New York Knicks player, joined the CBA in early 2010 and is still in China, playing for the Beijing Ducks. He is keen to capitalise on China's commercial opportunities by promoting his Starbury sports shoe range.

"He agreed to give a shot at CBA only after having looked into the market potential in China," Wang Xingjiang, the owner of the Shanxi Zhongyu Brave Dragons, the first CBA team Marbury played for, told Sports Illustrated at the time.

China's rapid economic ascent has made these signings possible, with Mr Wang pumping in cash from the fortune he made in the iron and steel industry.

"I don't think the CBA teams are making money, but the Chinese economy is robust enough that the companies that own the teams are in a better position to be spending," says Mr Beyer.

In China's football leagues, a willingness to pay for foreign players is even more apparent, even though the clubs generate modest revenues, a reported $3m a year in the case of the Chinese Super League's Shanghai Shenhua.

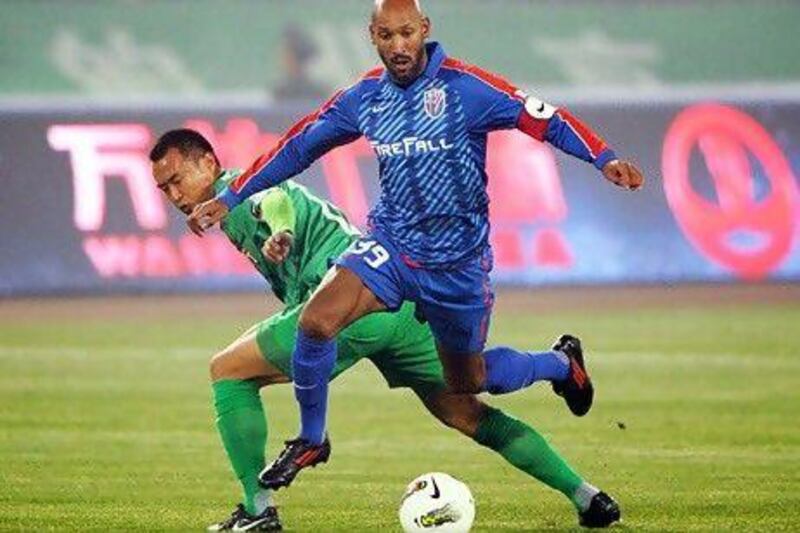

Yet this team signed France's Nicolas Anelka, who arrived this year on a free transfer, his new bosses agreeing to a 100m yuan salary. He will be joined by the former Chelsea player Didier Drogba, who announced the decision on his website, Reuters reported.

Shanghai Shenhua is owned by Zhu Jun, the chief executive and chairman of The9 Limited, a Shanghai-based online games company that had revenue of $16.9m last year. The rival Guangzhou Evergrande is bankrolled by the property tycoon Xu Jiayin.

At least the presence of top overseas players is attracting more fans. Reports indicate that the CBA's viewing figures in China have increased, while the NBA's have fallen, after Yao's retirement.

Despite the improvements, some analysts believe it will be tough for China's domestic leagues to flourish commercially until the perception of corruption is eliminated.

"Before they deliver results and clean up the image of football here, not many companies would want to align themselves too much with the sport and athletes," says David Yang, a special correspondent for the Wild East Football website.

twitter: Follow and share our breaking business news. Follow us

iPad users can follow our twitterfeed via Flipboard - just search for Ind_Insights on the app.