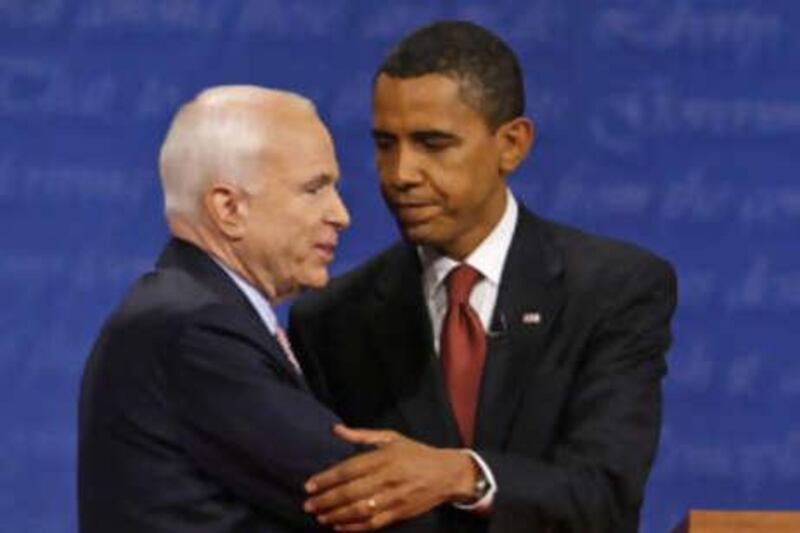

According to article two, section one of the US constitution, any native-born citizen 35 years or older and a resident of the country for 14 years is eligible to run for president. What the constitution doesn't say - but which is crucial to an understanding of how US foreign policy is made - is that only those willing to abandon reality for fantasy, or who can't distinguish one from the other, need apply. How else does one explain the stunning disconnect between the world as it was intellectualised in last week's presidential debate, which focused on foreign policy, and the world as it actually is? Neither Barack Obama nor his rival, John McCain, would acknowledge what pretty much everyone outside the debating hall at the University of Mississippi understands all too well: America's unipolar moment is over. The challenge for the next president is how to repair the damage done to Washington's image abroad, while unwinding its costly entanglements overseas. It needs to demilitarise its foreign policy and rebuild its diplomatic resources in response to a geopolitical landscape vastly altered since President Wrecking Ball turned himself loose on it eight years ago. And yet there was John McCain, lecturing Mr Obama for wanting to engage Iran directly and on a senior level, as if shrouding the regime under a flimsy embargo has done anything but heightened its oppression and intensified its craving for the bomb. Mr McCain spoke of victory in Iraq and said Baghdad will one day be a close US ally, though he didn't explain how a country so anti-Zionist could reconcile itself with Washington's unconditional support of Israel. He praised Iraqi leaders for passing a voting law, but failed to mention how they left the divisive issue of Kirkuk for future negotiations, rendering the legislation a dead letter. He repeated his vow to extend Nato membership to Georgia and Ukraine, omitting the fact that Moscow would consider such a move an act of war at a time when the US needs Russia's help in curbing Iran's nuclear ambitions. He repeated his call for a League of Democracies, presumably a cocktail circuit that would parallel Nato and subvert the UN in order to keep countries like Russia and Venezuela on the defensive. As if in fidelity with Mr McCain's script, the Russian president Dmitry Medvedev popped up in Caracas on Thursday to help Hugo Chavez, his Venezuelan counterpart, buy US$1 billion (Dh3.67bn) worth of new military equipment. Queue the "Axis of Autocracy". By now, Mr McCain should be aware that the US financial system is on the verge of collapse and the country is sliding towards recession. Prior to the debate, he made a brief stop in Washington to assist negotiators seeking an end to the crisis despite his self-confessed ignorance of economics and his remark only 10 days earlier that the US economy was fundamentally sound - thus confirming his earlier assertion. In fact, he only emboldened a Republican insurgency against President Bush's bailout package. With a fellow party leader like that, who needs an opposition? No matter. In his case for expanded military commitments abroad, Mr McCain gave no hint that his proposed tax cuts should be pared back, nor did he suggest that America's $600bn defence budget, nearly half the entire world's military outlays, should be trimmed. Apparently, global hegemony is its own reward. And where was Mr Obama in all this? In the tank with Mr McCain, believe it or not. However different the two men's temperaments and personal narratives, they both labour under the same potentially lethal delusions. Like Mr McCain, Mr Obama would increase defence spending beyond its galactic levels while cutting taxes, handing out energy rebates and spending $50bn to jump-start the economy. He supports enlarging Nato and wants to increase the number of US forces in Afghanistan to battle what the Pentagon calls an "insurgent syndicate", though even the defence secretary Robert Gates is said to be queasy about extending the "surge" conceit beyond Iraq. Even worse, Mr Obama would have the US twist itself deeper in the mire of Pakistan's tribal areas in search of Taliban units, despite an escalation of tensions between American and Pakistani troops in the area that has erupted into exchanges of fire. The gulf between the chaos on Wall Street and the pompous rhetoric at the University of Mississippi was vast, even by the mind-altering standards of presidential politicking. If there was a yardstick of how reality-deficient last Friday's display was, it was the lack of any reference to America's most urgent foreign policy imperative, the Arab-Israeli peace process, or of its most significant long-term challenge, the rise of China. In plotting their signature foreign policies, both Messrs McCain and Obama seem to be using Cold War-era co-ordinates. They are analogue innocents in a complex, digital world. To the extent that a nearly bankrupted America matters at all, this should be of concern to all of us. sglain@thenational.ae

Candidates have lost the plot of the crisis

According to article two, section one of the US constitution, any native-born citizen 35 years or older and a resident of the country for 14 years is eligible to run for president.

Editor's picks

More from the national