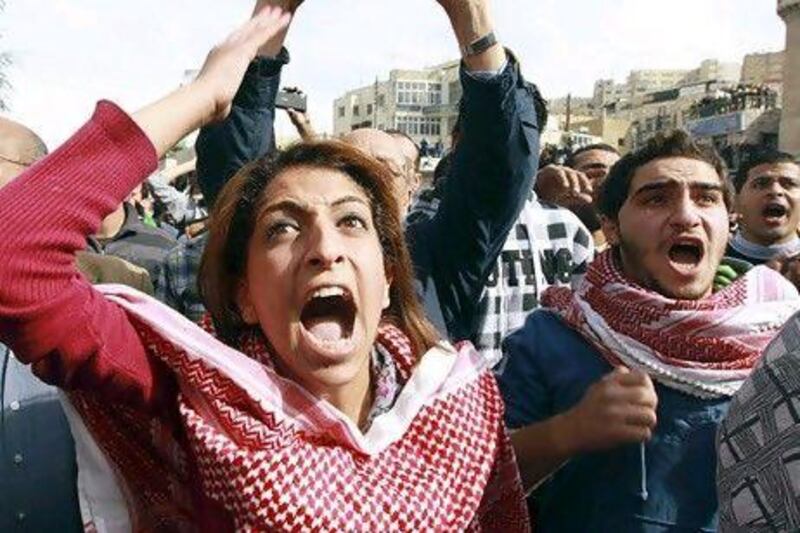

'To play with prices is to play with fire," read the placards of demonstrators around the Al Husseini Mosque in downtown Amman last week. More than 10,000 people marched to protest against the removal of fuel subsidies. Demonstrations and riots spread to several cities throughout Jordan, and slogans became increasingly political.

The government is increasing the price of bottled gas, used for cooking and heating, and diesel and low-grade petrol. This is to save some of the US$2.3 billion (Dh8.4bn) it spends annually on subsidies, almost a quarter of its budget, and the main reason for a deficit that has ballooned to $3.5bn.

The Muslim Brotherhood deputy Zaki Bani Arshid, part of the opposition to the government, presented no policy other than demanding the withdrawal of the price increases. Suleiman Hafez, the finance minister, announced on Friday that cash disbursements would begin to low- and middle-income Jordanians to cushion the blow of the subsidy removal. But the details of this compensation policy have been under discussion for two years.

Energy crises have a familiar pattern. There are warnings over years of inadequate provision for future demand, or vulnerability to cut-offs. But politicians resist charging higher prices to consumers, and important new projects are caught up in bureaucracy.

When the crisis does come, the country or state utility runs out of money, or the lights go out, and the realisation dawns that there is no quick solution. Then the political will and focus may finally be sustained over several years to implement deep reforms and build new power plants and pipelines.

In Jordan's case, the arrival of the crisis has been accelerated by the cut-off of gas supplies from Egypt due to repeated sabotage and Egypt's own shortages. Jordan has had to turn to expensive oil for electricity generation. The Syrian crisis next door has been a further blow to the economy.

Jordan is not quite as resource-short as it often appears to be. But none of the solutions to its energy crisis are quick and cheap. Hoping to start a liquefied natural gas terminal to receive imports by mid-2014, it is unlikely to get a hoped-for cut-price deal from Qatar. Iraqi gas by pipeline is an obvious option - but Baghdad has shown no urgency to seize this opportunity. Instead, Israel's new offshore gas, more than enough for its own needs, may capture this market and reinforce Amman's strategic dependency.

In the near term, with abundant sun, plans for renewable energy can help fill the gap, but its wind project has had several false starts.

BP is drilling for shale gas, and mining for "oil shale" is going ahead - a hydrocarbon-rich black rock that can be burnt in power stations or processed into oil.

A nuclear power programme has been in the works since 2007, but still faces major challenges of skills shortages, financing and water to be ready for the ambitious start-up date of 2019.

Jordan can continue to muddle through for some time. King Abdullah can make selective concessions, as he did in September when rescinding a 10 per cent increase in petrol prices. He can sack unpopular ministers and negotiate side deals with interest groups. The IMF's $2 billion loan in August came with the condition of raising electricity prices, but Jordan's strategic importance means the US and Arabian Gulf states will no doubt make more funds available if required.

Powerful friends give Amman the luxury of postponing tough choices. But it needs to combine its commitment to subsidy reform with real progress on new energy projects and systematic reform of social welfare. Otherwise, the government has no choice but to continue juggling with fire.

Robin Mills is the head of consulting at Manaar Energy, and the author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis and Capturing Carbon