A ski champion who popularised game-changing eyewear, the 'Father of Pac-Man' and a former chief of Sara Lee who provoked a debate about working moms – these are among January's obituaries from the worlds of business and economics:

Jean Vuarnet

An athlete and innovator, Jean Vuarnet died on January 2 at age 83.

When he won a gold medal for France in downhill ski at the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley, California, Vuarnet had an edge. He was wearing a new type of sunglasses that a ski-loving optician in Paris had given him in 1959 as a token of respect.

The sunglasses used new-fangled Skilynx lenses that improved contrast and enabled the wearer to more easily make out variations in the landscape – a handy distinction on a ski run.

After the Olympics Vuarnet and the optician, Roger Pouilloux, teamed up to market the glasses under the Vuarnet brand name. Made of scratch-resistant mineral glass, the yellow-tinged spectacles had allowed Vuarnet to better suss out the shape of the Squaw Valley race surface. In a 1960 poster promoting the sunglasses Vuarnet says: “They are formidable. At all times I see depth with precision.”

The glasses were not Vuarnet’s only innovation on the slopes – he was also a pioneer of the “tuck” position, which creates smoother air flow around the racer than a more upright position, and he was the first elite skier who used metal skis instead of wooden ones.

Vuarnet worked to popularise Vuarnets over the years. Today the company has stores worldwide and Vuarnets have endured as a symbol of cool: Jeff Bridges wore them in The Big Lebowski in 1998, and Daniel Craig wore them during an alpine scene in 2015’s Spectre.

For Vuarnet, the best part of business life was creating rather than sustaining. He once said: “What’s exciting is building. When things started to work, I was no longer interested.”

He was born in Tunis in 1933 but grew up in Morzine in the French Alps. His father, a doctor, had moved to the community in France’s Haute Savoie while Vuarnet was still an infant.

“I found myself in a place where ski and luge were the only things to do,” Vuarnet told the French newspaper Le Figaro in 2006.

His life had wonderful highs and a horrible low. In 1995 his wife, Edith, and Patrick, the youngest of their three children, were among 16 people who died in a murder-suicide involving the Order of the Solar Temple doomsday group. French police discovered the charred remains of 14 victims – arranged in a star formation – in a forest clearing near the Alpine city of Grenoble. Two other bodies were found nearby. Investigators said the policeman Jean-Pierre Lardanchet and the Swiss architect Andre Friedli fatally shot the others before killing themselves. Autopsies showed that most had taken sleep-inducing drugs.

Masaya Nakamura

Masaya Nakamura, the “Father of Pac-Man” who founded the videogame company behind the hit creature-gobbling game, died on January 22. He was 91.

In 1955 Nakamura founded Nakamura Manufacturing Company (later shortened to Namco) in Tokyo. It started out with just two mechanical horse rides on a department store rooftop, and went on to pioneer game arcades and amusement parks.

Pac-Man, designed by the Namco engineer Toru Iwatani, went on sale in 1980, at a time when there were only a few rival games (Space Invaders among them). The plucky yellow circle with the huge mouth was a huge hit. The game is estimated to have been played more than 10 billion times. It was non-violent, but just challenging enough to hook players into steering the Pac-Man for hours through its mazes on the hunt for ghostly tidbits.

The Pac-Man character adorns T-shirts and other merchandise and inspired animation shows, a breakfast cereal and even the nickname for Manny Pacquiao.

The idea for Pac-Man’s design came from the image of a pizza with a slice carved out. Nakamura reportedly chose the word “Pac,” or “pakku” in Japanese, to represent the sound of the Pac-Man munching its prey.

The game started out as an arcade item and then was played on the Nintendo Family Computer home console. It since has been adapted for mobile phones, PlayStation and Xbox formats. Other successes from Namco include Galaga, Ridge Racer and a drumming game.

Nakamura’s pet saying was that his company delivered varied and total entertainment. He took pride in having fun and games for his job.

Brenda Barnes

Described by Fortune magazine as having been a “hero to working moms”, Brenda Barnes died on January 17 at age 63 following a stroke.

She was the chief executive of the packaged-goods company Sara Lee from 2005 until 2010, when an earlier stroke prompted her to resign.

But it was in an earlier post that she achieved her greatest renown. In 1997 she quit her job as chief executive of PepsiCo North America to stay at home and raise her three children, who at the time were 10, 8 and 7.

“Barnes remained powerful,” Forbes wrote in an obituary, “even as she stayed on the sidelines serving as a director on numerous Fortune 500 boards. At the same time, she became a folk hero to many women, particularly moms who left top jobs to take care of their kids.”

However, some thought she had done a disservice to women who were fighting hard to get or keep executive jobs.

“I hope people can look at my decision not as ‘women can’t do it’ but ‘for 22 years Brenda gave her all and did a lot of great things,’” she explained to The Wall Street Journal. “I don’t think there’s any man who doesn’t have the same struggle. Hopefully, one day corporate America can battle this.”

After seven years at home she returned to the workforce in 2004, as she believed her children were ready to spend more time on their own.

Hired as president of Sara Lee, she was soon appointed its CEO. She spun off the company’s apparel brands, including Hanes and Playtex, which in total represented about two-fifths of Sara Lee’s assets.

After Ms Barnes resigned, Sara Lee ended up dividing into two, with the brand owned in America by Hillshire Brands and abroad by DE Master Blenders 1753.

Seven years ago, Barnes suffered her first stoke while working out at a gym near her home in the suburbs of Chicago. She spent many months in rehab. Her daughter, Erin, following in her mother’s footsteps, quit a job with Campbell Soup to be with her mother during the rehab process.

Leslie Koo

A Taiwanese businessman who refocused his family’s cement business, Leslie Koo died on January 23 after falling down a flight of hotel stairs. He was 62.

According to the Taipei Times, Koo was attending a Saturday night wedding banquet at the Regent Taipei when he suffered severe head injuries from the fall. He died the next morning.

Koo took charge of the family firm, Taiwan Cement, in 2003. The company was in a slump but he restored discipline and stepped up its push into China with a strategy of “start late, arrive early”.

In a 2007 interview with CommonWealth magazine, Koo explained: "In the past, everyone would speak of interpersonal harmony. These days, there's no talk about harmony. What we're pursuing is responsibility. It used to be, first deal with human relations, then get things done. Now it's, first get things done, then deal with human relations."

Taiwan Cement is now the world’s 12th-biggest cement company.

Koo’s father died in 2005. As a way of remembering him, Koo allowed three clocks on the top floor of the company’s head office to drain their batteries, and after that he let time stand still.

Walter Lange

Walter Lange, who fled East Germany in 1948 and returned four decades later to revive the high-end watchmaker A Lange & Soehne, died on January 17. He was 92.

Lange was the great-grandson of Ferdinand Adolf Lange, who founded a pocket watch workshop in 1845 and went on to make clocks for the kings of Saxony.

After the Second World War, East Germany’s communist government expropriated the company. It was merged into a state-run firm that continued to manufacture mechanical watches, marine chronometers and, from the 1980s, inexpensive quartz watches. Walter Lange, a trained watchmaker, fled the country to avoid being sent to work in a uranium mine.

In 1990, together with Guenter Bluemlein, Lange reformed the company, which is now owned by Swiss luxury goods maker Richemont. The company employs 770 people and has a reputation that rivals those of giants such as Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet. In January the brand exhibited its latest creations at Geneva’s watch show.

According to the horology website Hodinkee.com, Lange wore a first-generation Pour le Mérite tourbillon for special occasions, and an early yellow gold Langematik for daily use.

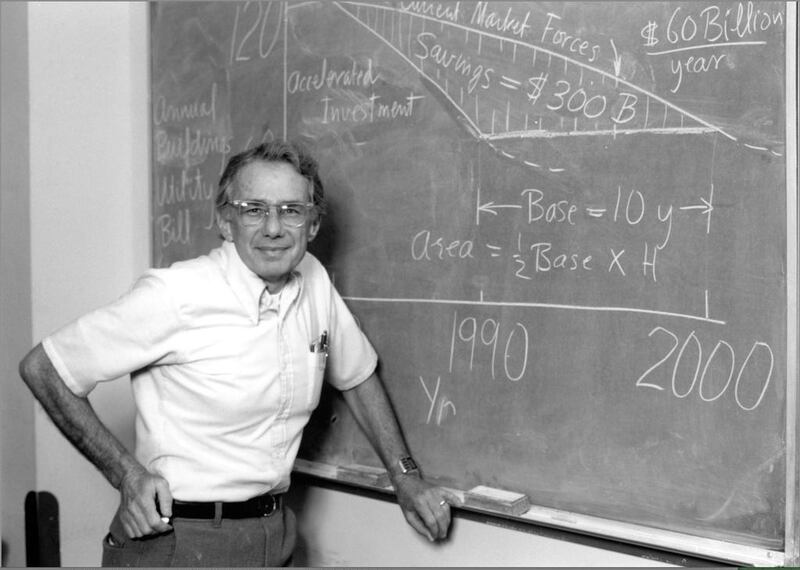

Art Rosenfeld

A pioneer in energy efficiency who was influenced by childhood years in Egypt, Art Rosenfeld died on January 27 at age 90. He was working as a nuclear physics professor at the University of California, Berkeley in the early 1970s when he became vexed by how mindlessly wasteful his colleagues were with energy.

This was at the time of the Opec oil embargo. So one Friday night (as recounted in The New York Times) at the end of the day he turned off all the lights on his lab’s floor. He calculated that over the course of the weekend, his handiwork saved the equivalent of 100 barrels of oil.

He became a zealot for energy efficiency. At a function in 1975, he sat next to Jerry Brown, then and now the California governor, and told Mr Brown that the need for a planned nuclear plant would vanish if California simply compelled fridges to be made with greater energy efficicency. Mr Brown introduced such rules two years later and the nuclear plant was never built.

Rosenfeld grew up during the Great Depression. When he was six the family moved abroad after his father, an agronomist, landed work as a consultant on sugar cane farming in Egypt.

“It was there,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in 2011, “that the child learned that resources weren’t infinite. His parents, budget-minded southerners, drove tiny cars to save on gas and insisted he turn off lights when leaving a room. These were familiar practices to the European children who attended his western-style school.”

Rosenfeld told the newspaper: “Electricity wasn’t dirt cheap in Europe and certainly not in Egypt ... Europeans only used half as much energy per dollar of GDP, and it was clear that their lifestyle was as good as ours.”

* Agencies and The National

business@thenational.ae