The Celtic Tiger is roaring again – but with a tentative note. The Irish economy, the fastest growing of any European country in the 1980s and 1990s, came to a juddering halt when the financial crisis of 2008 caught it unprepared and over-exposed to the property sector. In the slump that followed, GDP growth fell by nearly 20 per cent between 2008-10, the country's entire banking sector had to be nationalised and house prices plummeted, with the country's new class of property billionaires rapidly becoming minus-billionaires.

Overnight, one of the Western world’s most successful economies became one of its biggest basket cases, overshadowed in the EU only by Greece. But now Ireland is back, once again resuming its place at the top of the European league, with growth of over 7 per cent in 2017. So strong is the rebound that the Finance Minister, Paschal Donohoe, warned in December that he is prepared to raise taxes or postpone capital projects to ensure government spending “doesn’t accelerate economic overheating”.

Fitch, the ratings agency, lifted its rating on Ireland from A to A+ in December, the country is moving back towards full employment, household debt is declining, the population is growing again and house prices have rebounded strongly.

_______________

Read more:

Britain promises no 'Mad Max style' deregulation after Brexit

As we build a post-Brexit Britain, there is no more obvious partner than the UAE

May says UK seeks post-Brexit EU security partnership

_______________

Most important of all, the banks – the principal cause of the economic collapse a decade ago – are finally emerging from a disastrous decade.

The National Asset management Agency, the "bad bank" set up to deal with their balance sheet disasters, has done its job successfully and repaid all of its senior guaranteed debt ahead of schedule.

So why is nobody celebrating? In a word, Brexit. The people of the Republic in the south and Northern Ireland in the north do not agree on many things, but they are united in their concern that Brexit will be potentially disastrous for both of them. The Irish border, the only land border that will remain between the United Kingdom and Europe post-Brexit, has emerged as one of the most contentious issues in UK Prime Minister Theresa May's negotiations with the EU, threatening to derail the whole process. When I grew up in Ireland, crossing the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic was a serious and time-consuming business; at one point the Irish customs and excise service was the biggest employer in the country. But the removal of all border posts 20 years ago changed the whole manner in which trade is conducted between the two sides, with magnificent six-lane motorways linking Dublin to Belfast and Derry without a customs man in sight. Residents of the north drive south to fill their cars with cheaper petrol while southerners drive to Newry to do the weekly shopping at Tesco, the largest supermarket in the British Isles, where savings are substantial because of the different taxation levels. Now, with only 13 months to go before Brexit becomes a reality, no one knows whether the border will be physically manned, with inspections and delays for the thousands of trucks and cars which travel both ways every day, or whether Britain and the EU can agree on an invisible electronic border whereby companies would "pre-notify" customs online of shipments which could then be tracked on camera through number plates and driving licences logged without trucks having to stop.

That’s the model for the Norwegian-Swedish border, which works very well.

Mrs May emerged from her recent flying visit to Belfast with a political fudge, promising “specific” arrangements for Northern Ireland that would somehow maintain “full alignment” with the customs union and the EU’s single market.

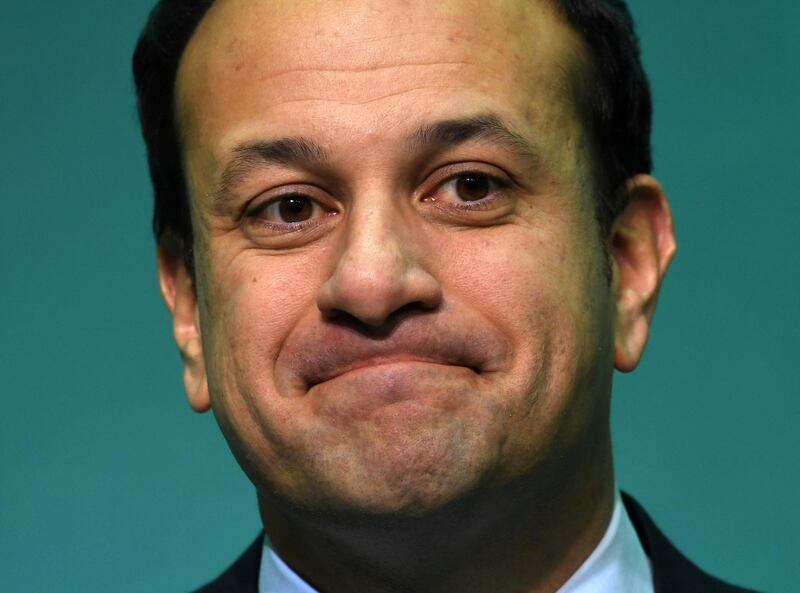

That is a potentially explosive solution for the Unionists in the north, but neither side understands yet how it might work in practice. Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief negotiator, says firmly that the UK’s decision to leave the customs union means border checks will be “unavoidable”; after meeting with Mrs May last week, the Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar warned that achieving a “frictionless” border will be the “tricky bit” in the Brexit talks.

"Calling it the 'tricky bit' is an understatement," remarked the Financial Times. "A solution to the border issue still looks utterly intractable."

The issue is not just one of inconvenience for truck drivers. The British market accounts for the vast bulk of Irish exports, much of which go through Northern Ireland, and trade barriers and tariffs imposed on a hard border could blow the whole recovery off course.

Ireland's economic rebound has benefited from an unexpectedly large haul of corporation taxes from multinationals with significant operations in the country, including Apple, Google and Facebook, who take advantage of its 12.5 per cent corporation tax rate – the lowest in Europe.

Thanks in part to such a windfall, the country is within range of a balanced budget in 2018 for the first time in a decade.

But that too is under threat, with Ireland under growing pressure from the EU to harmonise its tax rates, while many big US companies are being lured back to the United States by President Donald Trump’s tax cuts.

In the Irish capital there is real concern at the fragility and narrow base of Ireland’s economic recovery, which has yet to spread beyond the Dublin area, and its vulnerability to a Brexit shock at this time. For the moment, the Tiger is keeping his roar on mute.

Ivan Fallon is a former business editor of The Sunday Times