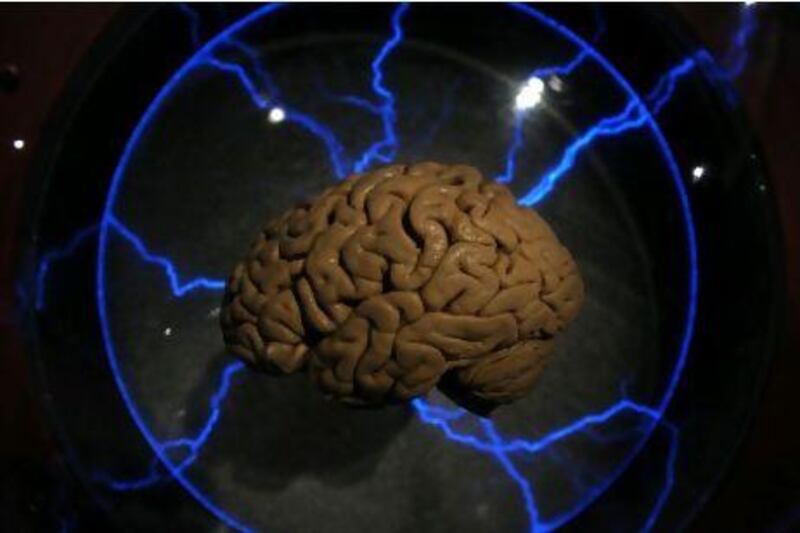

Economics is at the start of a revolution that is traceable to an unexpected source: medical schools and their research facilities. Neuroscience - the science of how the brain really works - is beginning to change the way we think about how people make decisions. These findings will inevitably change the way we think about how economies function. In short, we are at the dawn of "neuroeconomics".

Tomorrow's exclusives tonight:

Industry Insights e-newsletter Stay ahead of the pack and get the pick of the premium Business content straight to your inbox. Sign up

Efforts to link neuroscience to economics have occurred mostly in just the past few years, and the growth of neuroeconomics is still in its early stages. But its nascence follows a pattern: revolutions in science tend to come from unexpected places. A field of science can turn barren if no fundamentally new approaches to research are on the horizon. Scholars can become so trapped in their methods that their research becomes repetitive.

Then something exciting comes along from someone who was never involved with these methods - some new idea that attracts young scholars, and a few iconoclastic old scholars who are willing to learn a different science. At a certain moment in this process, a scientific revolution is born.

The neuroeconomic revolution has passed some key milestones recently, notably the publication last year of the neuroscientist Paul Glimcher's book Foundations of Neuroeconomic Analysis - a pointed variation on the title of Paul Samuelson's 1947 classic, Foundations of Economic Analysis, which helped to launch an earlier revolution in economic theory. And Mr Glimcher himself now holds an appointment at New York University's economics department.

To most economists, however, Mr Glimcher might as well have come from outer space. After all, his doctorate is from the University of Pennsylvania school of medicine's neuroscience department. Moreover, neuroeconomists such as he conduct research that is well beyond their conventional colleagues' intellectual comfort zone.

Much of modern economic and financial theory is based on the assumption that people are rational, and thus they systematically maximise their own happiness, or as economists call it, their "utility". When Samuelson took on the subject in his 1947 book, he did not look into the brain but relied instead on "revealed preference". People's objectives are revealed only by observing their economic activities. Under Samuelson's guidance, generations of economists have based their research not on any physical structure underlying thought and behaviour but only on the assumption of rationality.

As a result, Mr Glimcher is sceptical of prevailing economic theory, and is seeking a physical basis for it in the brain. He wants to transform "soft" utility theory into "hard" utility theory by discovering the brain mechanisms that underlie it.

It is likely that one day we will know much more about how economies work by understanding better the physical structures that underlie brain function. Those structures - networks of neurons that communicate with each other via axons and dendrites - underlie the familiar analogy of the brain to a computer - networks of transistors that communicate with each other via electric wires. The economy is the next analogy: a network of people who communicate with each other via electronic and other connections.

The brain, the computer and the economy are devices whose purpose is to solve fundamental information problems in coordinating the activities of individual units. As we improve our understanding of the problems that any one of these devices solves, we learn something valuable about all three.

Robert Shiller, professor of economics at Yale University, is the co-author, with George Akerlof, ofAnimal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism

* Project Syndicate

twitter: Follow our breaking business news and retweet to your followers. Follow us