The Libor rate-fixing scandal that rocked the British banking establishment in the summer moved into the High Court yesterday.

Barclays has been told by a High Court judge to hand over documents, emails and other details of 42 staff involved in the setting of interest rates, as part of Britain's first lawsuit linked to alleged Libor manipulation.

Barclays was fined US$450 million (Dh1.65 billion) in June by US and UK authorities after admitting to rigging Libor interbank lending rates.

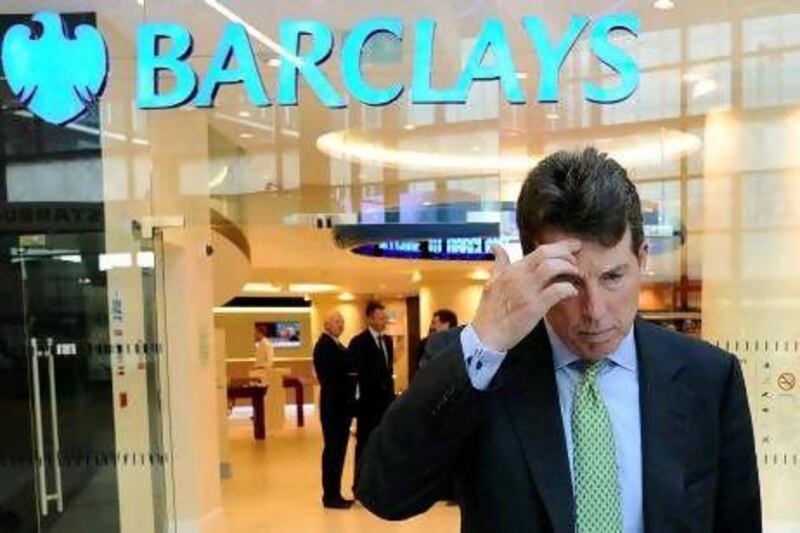

The man at the top back then was Bob Diamond. He finally stepped down over the Libor debacle but if he thought that would let him dodge the muck still flying in the aftermath, he will have to think again.

"Unfortunately, he is tainted, because Libor is one of the ugliest things I've seen in 40 years in and around the industry," says Christopher Wheeler, a Mediobanca analyst in London. Many others agree.

The American banker and former group chief executive of the giant British lender gained his BA in Economics at Colby College before taking an MBA at University of Connecticut.

And in Colby, a leading private liberal arts college in Waterville, Maine, today's students are not letting the Libor matter lie.

In 2003, Mr Diamond gave $6m to finance a Colby College facility, the humbly named Diamond Building. To a man of his means, that is just so much chump change.

In 2010, he was described as "the unacceptable face" of banking by the then UK business secretary Lord Mandelson, citing Mr Diamond's high level of pay - he scooped about £120m (Dh698.4m) from Barclays in the five years to his resignation - and lack of humility.

Early last year, Barclays announced Mr Diamond, 61, would receive an annual bonus of £6.5m, the largest of any chief executive of a British bank.

Since his fall from grace, however, his alma mater in Maine has become a focal point for student dissent over his role in the rate-fixing affair.

Mr Diamond, class of '73, was forced out at Barclays when it admitted to manipulating a key lending rate affecting $300 trillion in finance products worldwide.

Ever since the Colby trustees backed him as their chairman in August, a group of students and local activists have been rallying outside the Diamond Building to call for his removal. "It's not just what Bob Diamond stands for," says Gordon Fischer, a Colby senior who has helped to set up protests, including one that attracted scores of people last week

Colby's trustees met Mr Diamond in August to discuss his departure from Barclays. Afterwards, the board "strongly affirmed its support" of him as chairman, according to Sally Baker, a school spokeswoman.

"[The protests are also about] how the decision was made by the board to strongly affirm their support for him," says Mr Fischer.

Yet executives who have been tarnished by scandal are rarely forced to cut ties with schools and nonprofit organisations they have supported, says Stanley Katz, a professor of public and international affairs at Princeton University. Usually a trustee caught up in such situations is just not re-elected, he says.

"There's a big gap between that and forcing a person off the board," Mr Katz says. "What you're relying on is the common sense of the guy to throw himself overboard in the best interest of the organisation. At some point you're doing more harm than good."

Mr Diamond, who is not accused of doing anything illegal, declined to comment. "Until it comes to an indictment, people aren't going to ask him to step down," says Mr Katz.

And that rankles some in Maine.

"He's a very generous guy, but where did that money come from?" said Gary Lawless, a poet and a 1973 Colby graduate who runs a bookstore in Brunswick, Maine.

"The college is saying that if you don't get indicted, it's OK."

Following a public inquiry into the Libor affair, a UK treasury committee report to politicians in August said Mr Diamond gave "unforthcoming and highly selective" and his candour and frankness "fell well short of the standard that Parliament expects".

Meanwhile, back in the British High Court, Guardian Care Homes, a residential care home operator based in Wolverhampton, is suing Barclays for up to £37m over the alleged mis-selling of interest rate hedging products, which were based on Libor rates.

In what is seen as a test case for interest rate swaps mis-selling, the case is also set to shine a light on those involved in the bank's manipulation of Libor and how the rate-setting process was conducted.

It is not only Colby students who feel Mr Diamond should cut his ties with the faculty. "He is totally unfit to be involved with any college," says John Mann, a Labour Party MP who was on the treasury committee.

"The man was roundly condemned by our committee for his answers.

"We had the impression he was dishonest with us."

* compiled from Reuters and Bloomberg News