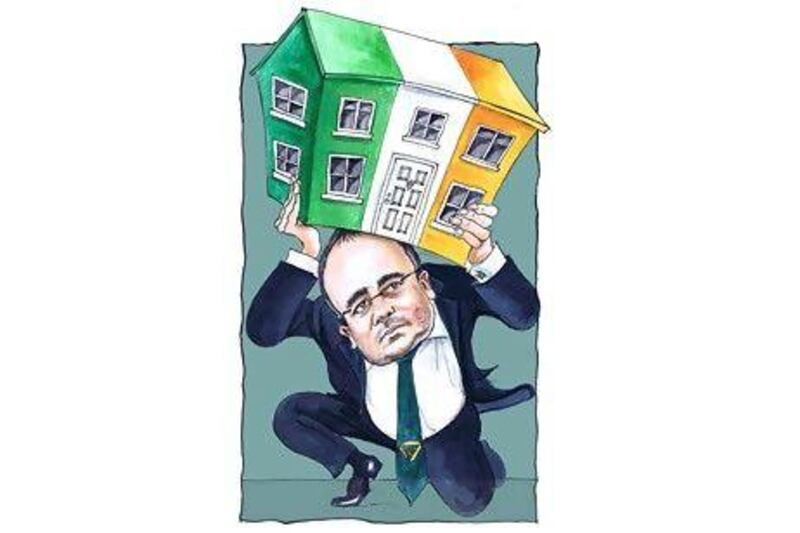

The chief of Ireland's bad bank is a man reckoned by some to be more powerful than the country's prime minister.

Brendan McDonagh manages a €74 billion (Dh351.7bn) loan book from Ireland's most indebted lenders and a property empire that stretches around the globe.

It could soon catch the eye of Arabian Gulf sovereign funds as Ireland's National Asset Management Agency (Nama) prepares to fatten up its most lucrative assets for sale.

Unlike most other asset managers, his role is not to boost the balance sheet of Nama, but rather to reduce it to zero over an expected lifetime of a decade having repaid the Irish taxpayer - at which point his job will theoretically be done.

The success or failure of his three-year-old agency could determine whether the Celtic Tiger ever roars again.

But the career civil servant from County Kerry on the west coast is not a man who likes to court publicity. Mr McDonagh is not, as they would say in Kerry, a "me feiner" (from the Gaelic for 'Myself').

Like it or not, the 44-year-old Nama chief executive has quickly become accustomed to having fingers pointed at him - from journalists, parliamentary committees and even passing old ladies.

As a director of finance, technology and risk at the National Treasury Management Agency he enjoyed relative anonymity for some seven years before he was appointed to run Nama in December 2009.

Overnight, he became a fixture of the evening bulletins and morning newspapers.

"You'd see people out on the street looking at you and they'd be saying, 'I've seen him somewhere before'. And as they walk past you'd hear them say, 'that's yer man from Nama'," Mr McDonagh says.

He recalls a recent incident trying to keep his warring children from tearing strips off each other while walking down the street.

"This lady walks past and says, 'Hmph, will you look at him with his big job and he can't even control his children'."

He laughs about that encounter, but the loss of privacy clearly jars with him.

"If I knew at the very start how extreme and invasive it was going to be, I might have thought differently about it."

He is in many ways the understated opposite to the brash developers who achieved celebrity status in Irish gossip columns for their trophy purchases and glamorous lifestyles.

The Irish banking crisis and ensuing property collapse has produced a feeling of public revulsion that is palpable everywhere.

It is the kernel of every hedgerow conversation in the way that the weather once was. It dominates the headlines and airwaves like a pall of pessimism that refuses to be shifted by any other news - good or bad.

And unlike in Spain, Greece or other European states buckling under austerity and unemployment, many Irish people blame their situation on just a handful of bankers and property developers who account for a large proportion of the debts inherited by Nama.

Just 29 debtors account for some 45 per cent of the Nama portfolio - three of them owing more than €2bn each.

It means the Irish crisis has been personalised to a far greater extent than anywhere else in Europe.

Ireland's €64bn bank bailout which preceded the creation of Nama is estimated to have cost every man, woman and child in the country almost €14,000 each.

That goes a long way in explaining the public contempt towards the bankers and developers blamed for bringing the country to its knees.

Mr McDonagh finds himself as a reluctant central protagonist in this narrative - buffeted by an angry public, probing select committees and defensive developers resentful of having to sell up and pay their dues. It is the ultimate thankless task in a country seeking retribution and atonement.

"We didn't create the problem," he says. "We're here to solve the problem."

But like a referee caught up in a rugby brawl that he didn't start - that doesn't stop him getting clouted from both sides, as well as the public in the grandstand.

"You can't take €74bn worth of assets out of the banks, along with 800 debtors, without people's lives being affected," he says. "Before Nama came along and before ever I was involved in this business, you couldn't go to a pub or a dinner without everybody knowing everything about house prices. Everyone in Ireland regarded themselves as an expert on property. Now they're saying, that wasn't such a good idea."

Much of the opprobrium related to Nama is reserved for its controversial move to pay salaries to some of its indebted developers.

Mr McDonagh concedes that some people find this distasteful but says it is the most cost effective way to manage assets.

"People think we're giving money to people personally - we're putting the money into the asset to produce a better return for the taxpayer," he says. "The cost of paying a developer to manage the asset is a lot cheaper than appointing a receiver, and that is in the best interest of the taxpayer. I can't get emotional about it."

Nonetheless, the payment of millions of euros to developers will offend many public-sector workers who stand to lose their jobs as a result of austerity measures. Should Nama struggle to raise the funds it needs to repay the Irish taxpayer from its asset disposals the policy may well come back to haunt the agency.

Many Irish people are already asking: if these developers really do know what they're doing, then how come they all need Nama to keep them afloat? Does celebrity gained from buying property with cheap money really equate to real in-depth real estate expertise? Or were they just gamblers who were lucky up to a point and aided by banks with inadequate risk management?

At a recent public accounts committee hearing, Mr McDonagh faced a marathon grilling from Irish politicians demanding answers to why some developers that would have otherwise been forced into insolvency are being paid up to €200,000 a year - as much as the prime minister.

"I am struggling to see any defensible rationale for paying a debtor €200,000 and holding his hand through the bad times, courtesy of the taxpayer, when the agency has a complement of 194 staff," said Mary Lou McDonald, a Dublin politician. "It may be an area of expertise, but it does not involve splitting the atom."

It is a popular complaint.

Three Nama developers are being paid salaries or "management fees" of €200,000, but Mr McDonagh says the majority receive less than €100,000. The agency has also received flak for not doing more to uncover hidden assets owned by its debtors.

He counters that Nama has been pursuing several of its largest debtors to prevent them from hiding or transferring assets they would otherwise be forced to sell. Nama says it has already reversed some €160 million in transfers from 31 debtors.

It has also been conducting asset searches worldwide for hidden properties - including in Dubai where the agency is pursuing at least one major debtor.

"Even if people have given personal guarantees and they shouldn't be transferring assets to third parties, they will do it. Where we see it, we go after it, and we have chased assets all over the world - from hotel suites to undeclared apartments to yachts to jewellery."

The UAE is also on the agency's radar for other reasons as a potential source of capital as it seeks institutional buyers for the best of its income-producing assets.

The Nama board last month approved a plan to create a huge fund aimed at attracting sovereign funds into which it would co-invest.

He believes the returns being generated by some of the property portfolio will be of interest to such investors, which could see him visiting the Emirates before long - for a brief respite from the glare of the Irish media and safely away from the belligerent old ladies of Dublin.