The Middle East and North Africa region is experiencing rapid change. But while attention is focused on political developments in countries such as Syria and Egypt, it is important to recognise that the changes most likely to shape the Arab world of tomorrow are not always the ones most likely to make headlines today.

Of these, the most important include efforts to tackle the "knowledge deficit" identified a decade ago in the Arab Human Development Report, which was sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme.

This is a challenge with profound implications for the security and prosperity of the region as a whole.

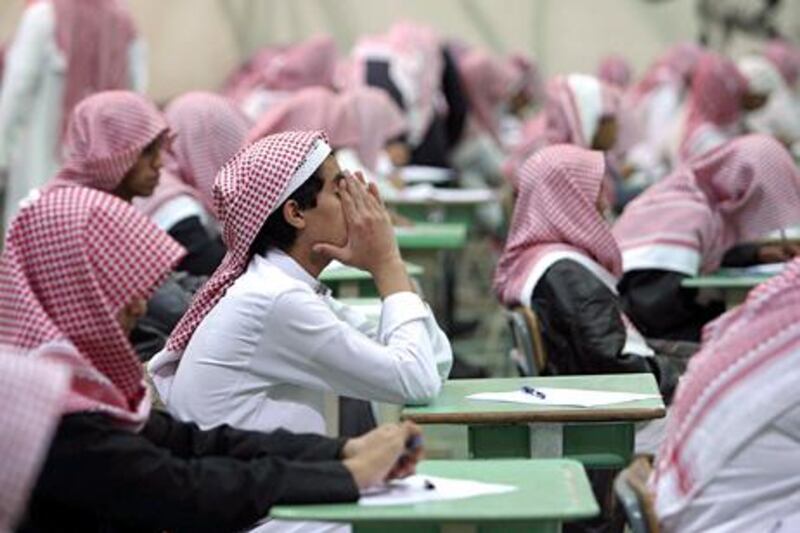

The ability to acquire and disseminate knowledge is a crucial determinant of competitiveness in the modern, globalised economy. Yet Arab countries still lag behind other economies according to key indicators, such as the publication of scientific research papers and the issuing of new patents. Basic literacy and enrolment levels have improved markedly, but standards in maths and science remain stubbornly below the international average, with little or no improvement over the past decade.

Compared with our main competitors, examinations put too much emphasis on the ability to recall facts and not enough on the kind of critical knowledge that drives innovation and expands the frontiers of discovery.

This is a major concern for business. Companies that want to compete at the top need access to the highest skills, so a failure to improve the quality of human capital will severely limit the region's economic horizons. There is a well- established link between foreign direct investment and levels of educational attainment for the same reason. Business therefore needs to become much more active in the debate about education reform, sponsoring new initiatives and forming partnerships with government and civil society.

This is about much more than commercial opportunity alone. It is about creating the conditions for harmonious social and economic development in conditions of rapid demographic change.

More than a third of the Arab population is now below the age of 15. With youth unemployment at 25 per cent, the risk is that a lack of opportunity will fuel instability and alienation instead. Finding productive and creative outlets for the aspirations of young Arabs is one of the most crucial long-term security challenges we face today.

Major efforts have been made to improve educational outcomes with considerable success. Literacy rates, especially among the young, have increased substantially and often stand in comparison with some of the best-performing countries in the world. In several Arab countries, equality of access for girls has been achieved and the problem is now lower educational attainment levels among boys; something normally associated with the West.

But with academic results remaining below international standards, the consensus among Arab governments today is that an "engineering" approach to educational reform, focused mainly on increasing inputs and expanding provision, has reached its limits. A new phase of reform must be aimed at raising the quality of education, moving beyond the limitations of rote learning and equipping students with the skills to be innovators and problem-solvers - in their careers and in their lives.

Oman, for example, is a country that typifies this shift in policy focus. It has made enormous progress in rates of educational participation and attainment since the 1970s, with school enrolment increasing from 900 to 600,000 in that time.

The priority given to education under the reign of Sultan Qaboos bin Said has enabled Oman to achieve the biggest gains in human development of any country since 1970, according to the UN. Now it has embarked on a drive for quality initiative, launched in conjunction with the World Bank last autumn, that aims to raise education standards to a higher level.

Priority reforms include performance monitoring and target setting, working more closely with parents to raise expectations (especially among boys), reforming teaching methods to encourage critical thinking and develop problem-solving skills, improving the quality of teacher training, expanding preschool education provision, reviewing teacher-pupil ratios and considering performance-related pay for teachers.

First, there have to be robust standards-setting and assessment processes, because it is only by measuring and comparing performance that we can identify weaknesses and improve results. Second, there needs to be a strong focus on teaching quality, because any school can only be as good as its teachers. The status of the profession needs to reflect its importance in a knowledge society.

Third, school governance should foster a positive learning dynamic at a grassroots level. Businesses should be encouraged to become more involved through school sponsorship, bringing valuable private-sector experience and enabling them to help young people prepare for the world of work.

Achieving these goals will not be possible without considerable effort over time. But nothing in Arab history or culture condemns countries of the Middle East and North Africa to the margins of the global knowledge society. Quite the contrary, learning and knowledge were intrinsic to our rise as a civilisation. With political will, proper investment and wise leadership, that past can also be a source of inspiration and hope for the future.

Mohammed Mahfoodh Al Ardhi is a director of Investcorp and the vice chairman of the National Bank of Oman