Long out of print and with copies almost impossible to find, the fine details of the nation's oil concessions were published in two volumes 30 years ago.

The Petroleum Concession Agreements of the United Arab Emirates was printed by a small British publishing house best known for its ornithological reference guides and it shone a light on to a sector even more obscure.

Reprinting every contract signed by the country from the 1930s, the first pages reveal that when western oil companies negotiated drilling rights in Abu Dhabi they promised the emirate's then Ruler, Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan Al Nahyan, an annual royalty of 500,000 rupees - and enough petrol for his small fleet of private cars.

The deal included a sovereignty clause that stated: "This agreement is a grant of rights over oil and cannot be considered an occupation in any manner whatsoever."

Much has changed since that concession was signed in 1939, such as the formation of the United Arab Emirates and a shift in the dynamic between Abu Dhabi and its foreign partners that gave the emirate more power over its resources. That was part of the nationalisation drive that swept oil-producing states including Venezuela and Saudi Arabia and led to the creation of Opec.

The 1982 book was a measure of transparency rare in an industry where only a handful of governments - Iraqi Kurdistan and Kuwait among them - have made such contracts public. Publishing such agreements opens governments to scrutiny over the terms they have brokered with foreign companies and can provide sensitive information to parties negotiating future concessions.

Such concerns did not deter Mana Saeed Al Otaiba, the oil minister at the time the book came out.

"Due to the importance of oil agreements to the economies of the oil-producing countries as well as to those of the industrial countries, and therefore to the world economy as a whole, we have thought it desirable to publish the agreement[s] concluded by the United Arab Emirates," Mr Al Otaiba wrote in the book's introduction.

But the window into the heart of the Abu Dhabi economy was opened only briefly.

The book is hard to find today - there is no copy in the National Library - and contracts signed after 1981 have not been published.

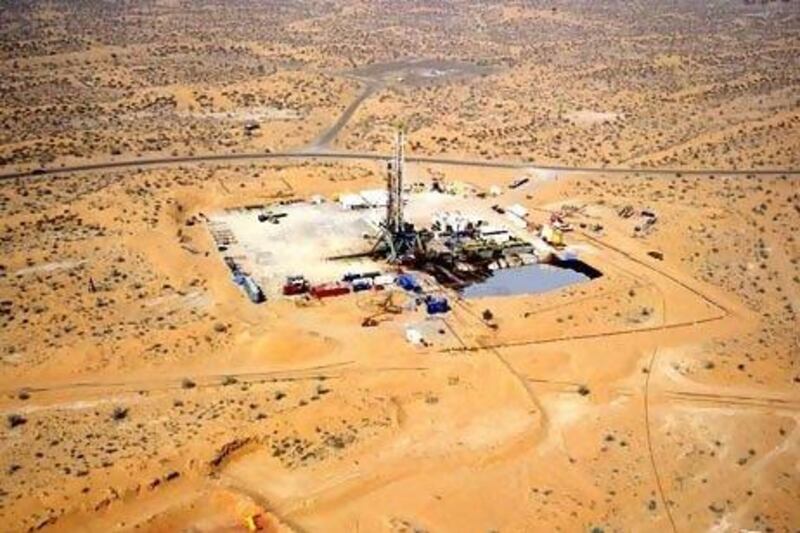

This opacity also shrouds the process of replacing Abu Dhabi's first oil contract when it expires in 2014 after a 75-year run. Referred to as the Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operations (Adco) concession, the rights include major onshore fields at Asab, Bab and Bu Hasa. A unique prize in the world of petroleum, this concession allows its owners to book billions of barrels of crude oil at the heart of the Arabian Gulf in a nation largely free of the political and security risks that threaten some other states in the region.

The concession has so much obvious appeal foreign partners have historically accepted extremely tough terms in return for the rights to a slice of the contract.

Together, the fields account for 1.4 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil output, half Abu Dhabi's capacity. The Government expects its new partner to expand Adco's capacity to 1.8 million bpd by 2017, part of a drive to expand the emirate's overall pumping capacity from 2.8 million bpd to 3.5 million bpd.

The original partners - ExxonMobil, Total, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, and Partex - are jockeying with new entrants, including national oil companies from China and South Korea and smaller western producers such as Maersk and Occidental.

The decisions will be made by the Supreme Petroleum Council, established in 1988 to effectively serve as a board of directors for Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc). The group includes members of the Ruling Family and trusted technocrats, such as Abdulla Nasser Al Suwaidi, the director general of Adnoc, but its proceedings are private.

Officials have spoken of a change to the current commercial model, where companies are paid a flat US$1 per-barrel fee, in favour of a framework based around a rate of return for foreign investors, taking into account new technology applied to fields and even the oil price.

Splitting the fields into separate joint ventures would allow the majors to deploy proprietary technology and take on greater risk.

The existing partners are predominantly western majors that normally target a 15 to 20 per cent return on any investment involving their latest technology, while China is believed to be ready to invest with a reduced 8 per cent return.

"There are no fixed rules," said Mohammed Sahoo Al Suwaidi, the chief executive of Adnoc's Abu Dhabi Gas Industries. "There is no one solution for each [joint venture]."

As well as commercial and technical considerations the geopolitical interests of Abu Dhabi are a factor with its allies from the US to Europe and emerging Asia. The emirate is turning increasingly towards the East, the buyer of most of its oil, and it has shown it is willing to shed partners from the old agreement. Last month, Adnoc sent letters to several companies - although not BP - inviting them to prequalify by providing basic information such as previous experience and number of employees. The letters revealed little detail about the process.

"We still don't know how the game will be," said Neri Askland, the Abu Dhabi representative for Statoil of Norway. "It is hard to be prepared if you don't know how they want us to bid. You know don't know if you're going to run 3,000 metres, 10,000 metres or something else."

New bidders say the absence of information gives an advantage to the existing partners that have detailed knowledge of the fields and the technology needed to keep the oil flowing. It also puts Abu Dhabi in the driver's seat.

"The more uncertainty that remains, the more that existing participants and the new candidates feel they have to make some new offer," said Chris Gunson, an oil and gas lawyer at the US firm Pillsbury in Abu Dhabi. "And that's definitely a benefit to Abu Dhabi."

In the original concession the contract could only be cancelled by Abu Dhabi if the western partners missed a royalty payment. The partners, on the other hand, reserved the right to exit the agreement any time.

"Such agreements, profitable though they may have been for a time, undoubtedly carried the seeds of their own destruction," warned Mr Al Otaiba in the book.

At the end of the contract in 2014, the oil majors face the prospect of having to walk away with no further compensation for the decades of investment in the facilities at the fields. But Abu Dhabi has the chance to create a new model on its own terms.