Davos might have all the glitz and glamour but businessmen seeking solutions to everyday problems in the Middle East should head to Kazakhstan in June for an alternative forum.

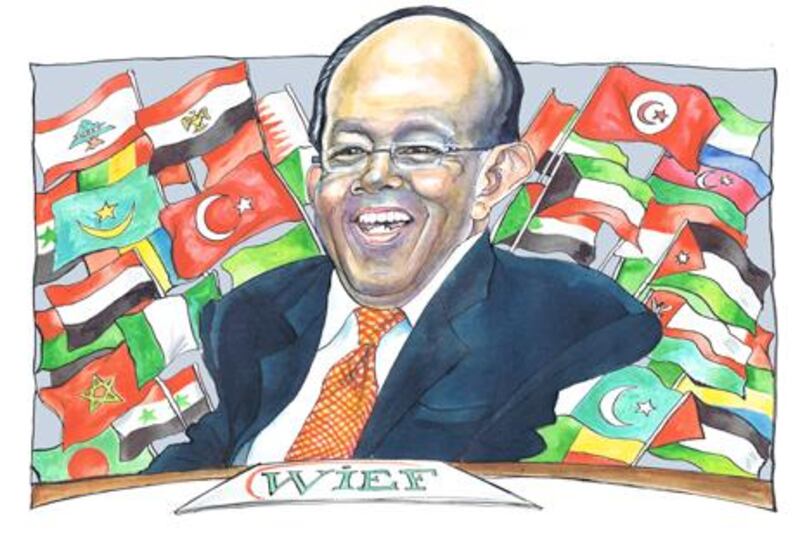

Not convinced? This is what Tun Musa Hitam, the chairman of the World Islamic Economic Forum (WIEF) Foundation, says of the summit: "They say we're like Davos - yes, somewhat. But [our forum] has some things that are attractive enough to make enough people see the difference between the World Islamic Economic Forum and other talking shops."

While delegates at Davos are griping about the prices of gourmet pizzas - 28 Swiss francs (Dh108.78), according to one Twitter post - food security for the 1.2 billion people of the Muslim world will be top of the agenda at the WIEF.

"Our top priority … in very simplistic terms, is the stomach. Let's fill the stomachs first," Tun Musa says.

The problems facing the Muslim world are poorly served by the global elite, he says. At a time of persistent unemployment, he believes it is particularly important to focus on entrepreneurs, and women and young people in particular. Islamic finance and halal tourism are also key topics of discussion.

The forum has grown in step with the Islamic finance industry, now estimated by HSBC to be worth US$1.03 trillion (Dh3.78tn). The first WIEF forum in 2006 in Kuala Lumpur attracted 600 participants. Last year's event was attended by 2,500 delegates from around the world.

But as a chance to meet leading businessmen in the Islamic world, display their achievements and learn from others, Tun Musa says the forum, crucially, must also attract non-Muslims who wish to exchange knowledge.

He says the Islamic world must take advantage of the internet - despite admitting he once fretted over the revolutionary potential of the fax machine.

"Most of my friends at my age don't even know how to send an SMS. They're like little children," Tun Musa says. But he acknowledges that for many millions of citizens, technological literacy and curiosity can be rewarding.

Now in his mid-70s, he has embraced the online world and is a tech-savvy operator. "When you find that a blog has been closed and you cannot access it, I know how to do it through other means, through different routes. I may be an old man, but I want to know."

Tun Musa was born in Johor in southern Malaysia in 1934. During his career, he has held a number of government roles, including education minister and minister of primary industries in the 1970s. He was appointed the deputy prime minister in the government of Tun Mahathir Mohamad, a role he held from 1981 to 1986.

Tun Musa's resignation in 1986 also turned out to be his farewell to politics."I managed to retire from politics and that's the happiest thing, because I read about what's going on, and I think, 'Alhamdulillah! I'm not in it.' I have to be interested, but not involved."

Since his resignation, Tun Musa has served as the chairman of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, become a board member of UNESCO, and the chairman of three publicly listed companies - one of which, the conglomerate Sime Darby, is among Malaysia's largest companies and one of the world's biggest producers of palm oil.

He is also an innovator. "I was one who, let me say, brought Club Med to Malaysia," he chuckles. "For some Islamic countries, it's a new thing to talk about tourism. In the old days, it meant new people coming and corrupting the morals and the behaviour of countries. Not any more."

The French resort chain, which has something of a risque reputation, arrived in Malaysia in 1979 after an overhaul of the country's tourism industry that Tun Musa oversaw as the deputy minister of trade and industry.

The benefits for the nascent Asian Tiger economy at the time have become clear. Tourism and economic diversification brought revenues of 53 billion ringgits (Dh63.82bn) in 2009, according to the Malaysian government. But that growth took patience and an ability to adapt Islamic traditions to the realities of capitalism.

"There are certain restrictions, but you need [tourist] dollars," Tun Musa says. "We need to work hard to adapt ourselves, which requires exposure, meetings and preparedness. But we will learn."

He admits he is perhaps "overburdening" himself with work, but still cherishes the opportunity to participate in public life. As the former deputy prime minister and still a very prominent businessman, he has taken flak from many of the bloggers he so strongly defends.

Following a recent cost overrun scandal at Sime Darby, one blogger called the company's management "incompetent", "obscene" and "repulsive". Another called for Tun Musa and his fellow board members to be incinerated and their ashes used as fertiliser.

It is an extreme form of criticism, but Tun Musa stresses the importance of companies and governments accepting such public outbursts are a fact of modern life.

"They have to learn very fast now, with the world becoming smaller," he says.

Business leaders are best able to help the Islamic world modernise and adapt to the needs of society if they are brought together to share ideas, Tun Musa argues.

That inevitably leads to public debate on the role of Islam and the politics of Muslim countries - two topics that are barred from the agenda.

"You waste a lot of time arguing about things that are better left for another forum," he says. "Politics will never be off the agenda because that's a major reality of the world.

"But within the context of the objectives of the forum and the methodology with which we approach it … the focus and concentration of it … is: let's just deal with economic matters and not get into contentious issues that often result in walkouts."

With the revolution in Tunisia this month stemming from rises in food prices and persistently high unemployment, along with protests in Egypt and Jordan, delegates in Kazakhstan may have a hard time keeping political questions off the agenda.

But Tun Musa says the forum must seek to influence social and political attitudes through other means. "We must concentrate on economic issues."

But if the Islamic world needs interaction with its secular counterparts to solve such pressing questions as food security and youth unemployment, what will the forum's Muslim delegates make of Kazakhstan?

The post-Soviet economy has courted foreign investment since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and came 59th in the World Bank's ranking of "ease of doing business" this year, just behind Rwanda and ahead of Vanuatu.

The country drew praise while chairing the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe for its handling of the crisis in Kyrgyzstan last year, when an explosion of violence, destruction and looting in southern Kyrgyzstan in June killed many hundreds of people following the toppling of Kurmanbek Bakiyev, the president, in April.

But observers including a former US ambassador have criticised its progress on corruption, human rights and press freedom.

"We don't worry too much about the political situation. That's number one," Tun Musa says. "Number two: whichever country you choose, you can always have doubts about its qualifications.

"We don't make judgement like that. We say, 'there's money to be made in a halal way - yes, let's go ahead.' That's why we extend ourselves even further. That's why we have non-Muslims. We have Russians, Norwegians, Swedish."

After all, he says, although westerners may be happy to criticise countries in other parts of the world when it suits them, the better-known annual summit, the World Economic Forum, is quite happy to hold events such as its Annual Meeting of the New Champions in China.

"As far as Kazakhstan is concerned, it has a lot of wealth, it seems to be managed well and it wants foreign investment, which … means it has to be global - and we have, somehow, to ignore the criticisms by certain quarters," Tun Musa says.

He acknowledges that while discussing politics and religion often leads to heated exchanges, such highly charged debates are not without benefits.

"Even the Sharia experts have to sit down and argue it out. But happily … there are arguments on religion of state - very contentious - and arguments on the secularisation of public finance. These discussions have been very constructive."

Tun Musa is well used to dealing with such emotive situations. He was part of the Malaysian delegation to the UN commission on human rights - including a spell as the commission chairman in 1995 - when the US and Iraq, China and Cuba were frequently involved in wars of words.

"I had to call their bluff," he laughs, "and telling off the Americans was great. For me to sit there banging my gavel and saying, 'Order, order, I remind the delegation of the United States that you are representing the sole superpower in this world …'

"Well, there was two seconds of shock, and then cheering and clapping."

Building a constructive relationship between the West and the Muslim East requires a sensitive touch.

Tun Musa wants the world to recognise that the West's captains of industry do not have the monopoly on innovation. If they can make the trip from Davos to Kazakhstan, he says, they would be welcome to take part in an exchange of good ideas.