Gawdat Bahgat hopes the Middle East can forgo a nuclear arms race.

On October 5 the United Nations nuclear conference of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) voted for a resolution urging the establishment of a Mideast nuclear weapons free zone (NWFZ) - an issue that has been on the IAEA conference agenda for 16 years. Alas, there is little reason to believe it will succeed now. Five NWFZs have already been created: in Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, South East Asia, Central Asia and Africa, covering approximately 1.8 billion people in 111 countries.

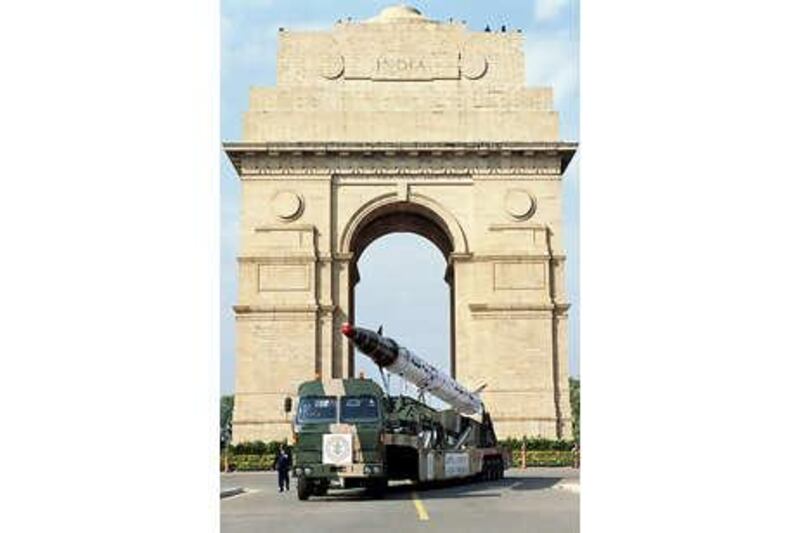

But nations continue to seek nuclear weapons, and will continue to do so in the absence of frameworks that assure them security in exchange for non-proliferation. NWFZs in other regions have been highly successful, but there are serious obstacles to its adoption in the Middle East - where, ironically, it is most needed. Since the United States built the first atom bomb in 1945, several countries have acquired nuclear capabilities, and others have tried and failed to do so. The more dramatic the perceived threats to security, the more determined states become to acquire nuclear weapons. But the search for status and respect also influences their choices, and the acquisition of nuclear weapons has indeed conferred prestige and political influence - at least initially. India and Pakistan, which both declared themselves nuclear powers in 1998, have gained special status on the international scene - seen clearly in the US-India nuclear co-operation deal signed earlier this month.

In 1968 the Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) was opened for signature. Two years later it entered into force. Despite the development of weapons by a few non-signatories - India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea - it is now the most widely adhered-to arms control treaty in history. And while it has some fundamental flaws, the NPT has been essential in containing proliferation and re-enforcing the international non-proliferation regime. In the 1950s and 1960s there was global concern that tens of countries would acquire nuclear weapons. A few decades later only four countries have been added to the original five. Another country, South Africa, made the transition from an undeclared possessor of nuclear weapons to a responsible participant in the nuclear non-proliferation regime - the first nation to develop nuclear weapons and then renounce them.

But any successful non-proliferation policy must also address the roots of regional instability that drive the demand for nuclear weapons. Middle Eastern states will feel motivated to acquire more destructive arsenals as long as they feel threatened by the arms of their neighbours; proliferation begets more proliferation. The two major obstacles to regional disarmament are Israel's undeclared nuclear arsenal and the controversy over Iran's apparent attempts at building nuclear weapons. Israeli leaders believe that nuclear weapons will shield them from a future Holocaust, and inflammatory rhetoric calling for the destruction of Israel reinforces this perception. Israeli policy has therefore been to maintain its regional nuclear monopoly while denying its adversaries such capabilities.

Iran and the other Arab states, however, see Tel Aviv's nuclear capability - and military supremacy - as tools to enforce the occupation of Palestinian territory. Indeed, most Arab governments view the Israeli nuclear arsenal as a threat to regional security, and accuse Western powers of applying a double standard on proliferation. Many Arab officials have argued that as long as Israel maintains its nuclear option, Iran and other regional powers will have incentives to seek similar capability.

For the last several years the United States and other major powers have accused Iran of seeking nuclear weapons, and American, Israeli and some European officials have stressed that they will take drastic measures to prevent such a development. The UN Security Council has already imposed three rounds of sanctions on the Islamic Republic, while the IAEA, which has not confirmed that Tehran is developing weapons, has regularly expressed dissatisfaction with Iran's limited co-operation.

The response of the Arab states can be described as cautious. Arab governments believe that if Iran's nuclear program is for military purposes, it is not aimed at them. Tehran does not identify the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states as a threat to its national security. The GCC states would not adopt unilateral sanctions against Iran, but will abide by those imposed by the United Nations Security Council. They are less concerned about a direct Iranian nuclear attack than an American or Israeli military operation against Iran. Another war in the Gulf would have a negative impact on political stability and economic prosperity in the region. They are against nuclear weapons in Iran but also against an Israeli or American military strike on the country's nuclear facilities.

The war in Iraq, the diplomatic confrontation between Western powers and Iran and the lack of any meaningful accord between Israel and the Palestinians all point to a high level of instability and mutual suspicion between all parties. But these same conditions underscore the need to take a fresh and serious look at all proposals to reduce tension and prevent further nuclear proliferation. Despite serious efforts, regional powers have failed to achieve a nuclear parity with Israel, and the establishment of a NWFZ is the only plausible path to military balance in the region. But three decades of proposals to this effect - in the UN General Assembly, the Security Council, and elsewhere - have been unsuccessful. Despite peace agreements between Israel and two of its neighbours (Egypt and Jordan) and years of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians, the region is no closer to a NWFZ.

The United States has promoted its own version of regional security, based on creating alliances between Israel and certain Arab countries to isolate Iran and its allies in the Arab world (Syria, Hizbollah and Hamas). An important pillar of the US security strategy in the Gulf is to improve the GCC states' defence capabilities through arms sales. The Middle East has generally been the largest arms market in the developing world. Besides Israel and Egypt, the GCC states have been the largest purchasers and recipients of arms from the US. In July 2007, the Bush administration announced new arms sales worth around $20 billion to the GCC. Announcing these deals, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said that they were intended to "help bolster forces of moderation and support a broader strategy to counter the negative influences of al Qa'eda, Hizbollah, Syria and Iran."

Any realistic proposal to establish a NWFZ in the Middle East will have to accomplish three main aims: first, it must be part of a comprehensive strategy for peace in the Arab-Israeli conflict, the only conceivable hope to encourage Israel to follow the example of South Africa and give up its weapons. Second, it must address non-nuclear weapons of mass destruction, which continue to proliferate and third, it must also be accompanied by similar attempts to reduce the proliferation of conventional weapons, and an end to the arms races that diminish prospects for stability in the region.

Nuclear weapons did play a decisive role in ending the Second World War, but in the following decades, they did not help Moscow in its war in Afghanistan or prevent the dissolution of the Soviet Union. They did not enable the Israelis to impose their will on the Palestinians or the Lebanese. And they did not bring victory to the United States in Vietnam in the 1960s or in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s. In short, nuclear weapons have proven of limited, if any, utility in recent decades.

A NWFZ in the Middle East remains more mirage than reality: Israel is highly unlikely to dismantle its nuclear arsenal, and Iran or another country may acquire its own weapons. But the future is not completely bleak: prospects for regional peace do exist, and there are signs that membership in the nuclear club may pay diminishing returns. The rising geopolitical strength of China - which possesses a nuclear arsenal smaller than that of Russia and the United States - suggests that economic and not military power is the key to regional and global prominence. The investments by Gulf states in economic infrastructure, rather than arms, suggest the region is on the "right side of the future".

Gawdat Bahgat is the director of the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania and the author of Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in the Middle East.