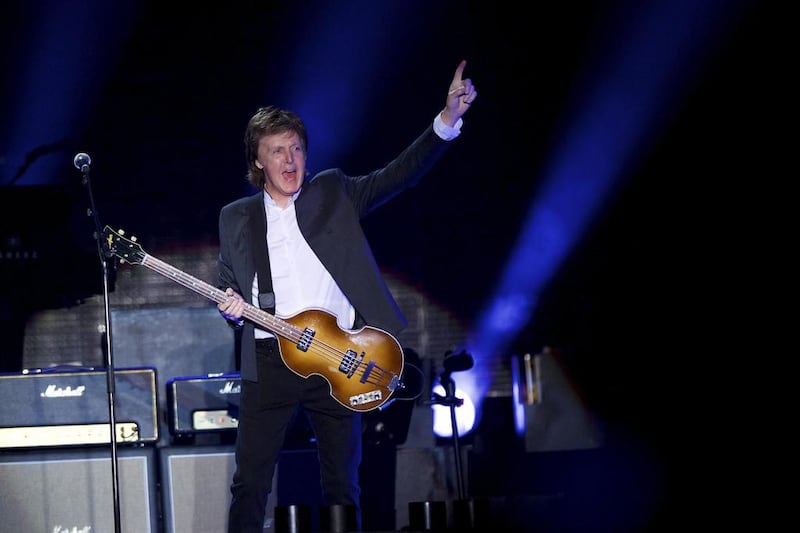

Better known to some these days as that old guy playing guitar with Kanye West and Rihanna in the FourFiveSeconds video, Paul McCartney’s impressive CV includes a James Bond theme tune, a substantial classical music oeuvre, an abundance of solo albums and a tidy stack of albums recorded in the 1970s with Wings.

Then there is also the not-so-trifling contribution he made with John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr to a certain Liverpudlian outfit that changed the face of pop music in the 1960s.

Dating back to his skiffle days with first band The Quarrymen, as a 16-year-old in 1957, McCartney is fast approaching 60 years in the music business. That’s hundreds, maybe thousands of songs written and recorded in various guises.

A distillation of the solo and Wings portion of his extensive career was recently released in a mammoth compilation. Titled Pure McCartney, it was released in multiple formats: as a 39-song double CD set, a 41-song four-record vinyl set and a deluxe 67-song set spread over four CDs.

In essence, it is another example of what we know as a “Greatest Hits” – or more accurately, “Best of…” – compilation. As McCartney said of the release: “Me and my team came up with the idea of putting together a collection of my recordings with nothing else in mind other than having something fun to listen to.”

The collection is just one of several eclectic career retrospectives released in the past few months, including collections by the likes of Jason Derulo (Platinum Hits), Placebo (A Place for Us to Dream) and Aha (Time and Again). Up until about a decade ago, these releases would earn such acts a healthy pension fund – and in many cases, their assured success would eclipse any of their previous releases.

A scan through the United Kingdom's top 20 selling albums reveals that six are greatest-hits packages: the top two being Queen's Greatest (1981) and Abba: Gold (1992), with more than six and five millions albums sold respectively.

But considering that most people now listen to music online, with plenty of these songs available on Spotify and Apple Music, what purpose does the career summarising compilation, or greatest hits, serve in an age where we have ready and easy access to almost everything almost everyone ever recorded?

Aren’t there already plenty of fan-curated “best of…” playlists, plus all the albums, including previous Greatest Hits-style records, already available at a click? This means greatest-hits collections do not sell nearly as many copies as they used to.

When The Who released their Then and Now collection in 2004, for example, it peaked at No 5 in the UK album chart. Ten years later, The Who at 50 compilation, released as the band set off on their farewell tour, only managed to reach No11 on a chart where the number of sales required to reach the top spots is much lower than it was a decade ago, as a result of the rise of streaming. The question, then, is what is so special about McCartney's release that it should pique our interest?

Fans have long argued against the greatest-hits concept on the grounds that it is a cynical money-sucking ploy by record companies to fleece hardcore fans, or because the song selection often neglects particular tracks or sections of an artist’s career.

Taken to ridiculous extremes, some classic rock bands, such as Steely Dan, have more greatest-hits compilations to their name than studio albums.

The greatest-hits album has been around since the early days of commercially released recorded music. The format served a practical purpose: in the days before long-playing (LP) records, an artist’s best cuts would make it onto 78rpm discs and then into album books that collected an artist’s most popular tunes. Starting in the late 1940s, the best-selling tracks could be compiled and sold in the handy format of the LP record.

The earliest LP albums, by artists such as Frank Sinatra, were greatest-hits albums of a sort – they included songs from the artist’s live repertoire that were hand-picked to be recorded and cut to vinyl.

The first Elvis Presley album, for example, was a compilation of his remarkable run of hits from his 1954 Sun Studios sessions, through to his 1956 recordings for RCA.

It was jazz artists who first began to shift away from this form and embraced the freedoms, in terms of duration, afforded them by the longer playing times of the LP.

Artists such as Charles Mingus (with Pithecanthropus Erectus in 1956), Miles Davis (1959's Kind of Blue) and Sinatra (with 1959's In the Wee Small Hours), started making themed, or concept, albums that stretched beyond the confines of the three-minute hot take.

Eventually, rock and pop stars started to take notice of this trend. The Beatles took their cue to start producing albums such as Rubber Soul (1965), which unleashed the concept album as an artistic statement in an era that a year later spawned the likes of the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, The Kinks' Face to Face and Love's Forever Changes in 1967.

Such album-length song suites became the calling card of any band or artist worth their weight in gold records.

In response, the greatest-hits album assumed the position it retains today: as an avenue to introduce artists and the potential jumping-on point for the new fan, or the condensed all-killer, no-filler summation of an entire career, or a section of one.

The 67 tracks on Pure McCartney are probably an example of the latter and a fair – rather exhaustive – summary of his post-Beatles work.

Best of all, the set was curated by McCartney himself and not clumsily assembled by record company staff or a computer algorithm.

artslife@thenational.ae