There is a moment in Black Gold, the partly Qatari-funded film about the discovery of oil in the Arabian Peninsula of the 1930s, when the two Arab princes meet in the desert, surveying the empty dunes that have suddenly become so valuable to them. The audience is meant to identify with either the traditional Prince Auda or the ultra-moderniser Emir Nesib. It is a moment that asks the audience to choose sides, to pick ideologies, to imagine what type of nation they would build themselves.

Films can be more than mere entertainment, they can tell people the stories of themselves and the stories of their nations. Black Gold can be read as a foundation myth for the modern Gulf states, a way of articulating the tensions between the old and the new, between competing visions of what these new nations are and will be, inherent in the foundation and rise of new countries.

Black Gold is the third full-length feature film of recent years that puts the region on the big screen and explicitly tries to tell a story about a nation. City of Life was the first Emirati film to do that, followed by Sea Shadow.

To watch them is to watch an evolving narrative about the collective identities of the Gulf countries, to see the themes that will one day form the bedrock of visions of the region.

***

A nation's identity is complex, a tapestry woven from historical events, from parts of history retold in stories and in schools, the accumulation of remembered events, celebrated figures and shared culture. In important ways, it is created or at least shaped by specific decisions, often political ones: which historical periods are put on school curriculums, which historical figures are celebrated nationally, which stories from the past are told and retold, used as examples to emulate or remembered as lessons to be learned.

These stories can evolve, sometimes rapidly. The national story of South Africa changed dramatically in the 1990s when Nelson Mandela was released and apartheid was dismantled. A large part of the modern story of a relatively new nation was altered, and today the apartheid era is rightly seen as an aberration, a stain of shame. Millions of South Africans had been brought up with the idea that what they were doing to their black compatriots under apartheid was benign, or necessary, or perhaps even noble. As the politics changed, so did the national story. Now that period is recognised as a time of extreme views and bankrupt policies.

Beyond politics, culture also plays an enormous role, often an accidental one. In the days of the Soviet Union, many writers and artists were banned and others given state approval. The same occurs today in countries all across the world. Yet culture – in the form of books, films, television and music – is harder to suppress these days and harder to regulate. Success depends on too many factors, from the cost of the production, to the attractiveness of the cast. The stories that become popular are not always those that fit the interpretation of the past favoured by politicians or a ruling elite.

A running theme in the 2008 film W, a biopic of US president George W Bush, is his relationship with his father, president George HW Bush. The film strongly implies Bush Sr was disappointed in his wayward son and attributes much of Bush Jr’s policies during his presidency to a psychological attempt to surpass daddy. Critics, both left and right, cried foul: as tempting as it is to see such psychoanalytical overlays on policy, the truth is that Bush Jr’s policies were formed in the cauldron of the times. America was not a canvas for Bush to play out his daddy issues.

But so often film can create reality, or at least frame it for so many people that it forms a de facto historical narrative, an interpretation of events that becomes part of the bedrock beliefs of a society. In that way film, perhaps, in this globalised and visual age, more than other forms of storytelling, becomes more than mere entertainment: it can actually tell citizens the stories of their nations.

America, in particular, has been especially good at this, for reasons that parallel why the Gulf region needs to tell its stories. A relatively new country that draws its citizens from scores of nations, America needs a particular narrative to tie all of these disparate experiences together. It is also a large country of more than 300 million people – for most Americans therefore the entirety of America is unknown to them. The reality of life in, say, Alabama or Oregon is going to only ever be experienced through television or film. Most Americans don’t really know how the other parts live.

The final piece of this is the film industry, which remains hugely popular in America itself (and, in significant part because of the English language, around the world) – that so many Americans go and watch American films allows that industry to thrive and create even more films. Countries without significant numbers of domestic cinemagoers – Italy, for example – struggle to sustain a domestic film industry.

That same process is now underway in the Gulf, as the region develops and begins to tell its national stories on film, on television and in culture. Some of the same underlying reasons that drove America to tell its national story to its people can be discerned in the Gulf today. Firstly, these countries are new: with the exception of Oman, not one of the GCC countries existed prior to the 20th century. They are cosmopolitan, composed of dozens of nationalities; they are developing extremely rapidly, so that someone who lived in Dubai in the 1970s would hardly recognise the city today and its way of life. And they are rich, which allows access to education and the funds necessary to create films.

One example of a recurring theme in American cinema explains why films that tell the story of a nation can be so important – and have far-reaching consequences in explaining, framing and in some way recreating the past. That theme is the national obsession with 1950s small-town America. In the popular imagination, America of the 1950s was close to ideal: it was a land of small towns with close-knit, law-abiding citizens. Neighbours looked out for each other, children played in the yard together, safely enclosed by white-picket fences. There were two cars in the driveway and when the father came home from work – because there was no unemployment – mother and cherubic children were there to greet him over a home-cooked meal. This was before the promiscuity of the 1960s, before the social contract was changed, before society’s bonds were broken, before the stress, anxiety and chaos of modern life took over, before America – so the narrative goes – fell into social decline. In reality, of course, the 1950s were barely like that: although such small towns did exist, the country was riven with racism, with the 1950s seeing the start of the civil rights movement. The Cold War was beginning and the country was still dealing with the legacy of the Second World War.

That idealised past has been created in significant part by its repetition through film. So much so that it has become a trope of American public life – politicians now attempt to persuade the public of the strength of their policies by promising to take them back to the safety of the 1950s, a 1950s that simply never existed.

It is important, though, to recognise that these films are not false, in the sense of selling the public a lie. Rather these films are working within a framework of ideas. Americans, like all people, want to have a sense of who they are, want to feel they are part of a shared identity. These films tell Americans what they were and remind them what they could be.

***

What themes, therefore, can be discerned from the current crop of Emirati films? What, in the telling of the silver screen, is the United Arab Emirates?

By looking at the themes of City of Life and Sea Shadow, it is possible to discern the ideas that will form the narrative of the Emirates over the next few years. It is not the national story: that will not be written in one film or in one decade. But it is a process. Piece by piece, as with the cities of the country, the narrative of the country is being built up, every fragment of culture building on the one before it, so that eventually there is a body of work that tells Emiratis who they are, and what the world around them looks like.

Start with City of Life (warning: spoilers to follow), which was the first locally made feature film to put Dubai on the big screen. City of Life is really a triptych of stories from three parts of society: Emiratis, both ordinary and privileged; expatriates, as typified by a well-off, amoral Brit; and workers, embodied in the film by an Indian taxi driver. It is explicitly a film about the city; it is meant to tell the story of Dubai more than the story of any one particular segment of society.

City of Life excels at showing parts of life in the UAE that few have the chance to see. This is especially evident in the story of Basu, an Indian taxi driver striving to make it as an actor.

For a good many expats and Emiratis, the sight of a labour camp is something new – few of us have really visited one.

The fragments of Basu’s life also ring true: when, whilst driving, he pulls out photographs of his parents to give him the strength to endure, it reminds viewers of something they already suspect is true.

Yet the arc of Basu’s development in the film is different to the trajectory he might follow in an American film, reflecting the different circumstances of the Emirates and how the country sees itself. In a mainstream American movie, Basu would go from driving taxis to following his dreams, to making it big. That’s the American arc, the story America tells itself about who it is and what it represents. But the Emirates isn’t like that. It isn’t, yet, an aspirational place, in the way America is, because, of course, it is a land full of migrants, who will, at some point, leave.

Ultimately, City of Life is a story of redemption; the city saves the lives and ambitions of its characters. It offers them opportunities they would not have elsewhere.

Sea Shadow, by contrast, is a story of loss. A coming of age drama centered on the life of two friends in Ras Al Khaimah, Mansoor and Sultan, it is ultimately about personal loss, about missed chances and wrong turns. When the love interest of one of the boys moves away, he realises how much he was complicit in pushing her to leave.

But Sea Shadow is also about the Emirates, in a very small way, about the development of the region.

“I don’t know how long he’s going to stay in this place,” one of the characters tells his friend, after urging his father to move from Ras Al Khaimah to a better life in Abu Dhabi.

“It’s not just your father,” says his friend, “A lot of people are like that. Like my mother says, they’ll stay here as long as there’s water in the sea.” Read in that way, the film is also about moving on, about what rapid development means for a conservative region. As much as the rhythm of small-town life is idealised, there is a strong sense that moving to the big cities is inevitable, that the future is urban. It is telling that in the whole film, every character who, it is implied, seeks a better life, finds it by leaving: Mansoor’s other love interest marries a man from Al Ain; Jassim – the character who tries to persuade his father to move to Abu Dhabi – eventually takes his sisters with him. Even Mansoor, in the final scene, gains the courage to follow his heart by diving into the sea, leaving behind the earth.

***

Both Sea Shadow and Black Gold are still being placed in front of audiences. Sea Shadow, which was produced by Image Nation Abu Dhabi, a company owned by Abu Dhabi Media, which also owns The National newspaper, was recently shown at the Palm Springs International Film Festival in the United States. Meanwhile, Black Gold is now on general release in the UK.

The pressing question for the Gulf is where the next film about the region will come from. This is more complicated than it sounds, because films and filmmakers grow organically – they need the soil of culture from which to emerge.

Peter Scarlet is the executive director of the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, now in its sixth year. There are a splattering of these festivals across the Gulf now. Dubai and Doha both have their own, each vying to bring the best of international film culture to the region. Others, such as the Gulf Film Festival, taking place next month in Dubai, have a more regional focus, aiming to celebrate local and regional film culture.

"I think what a festival does if it's a truly international festival is it's a meeting place, a point of encounter," says Scarlet, who was previously the artistic director of New York's Tribeca Film Festival. "This is a chance for [Emiratis] to be exposed to and to talk to and to have interactions with filmmakers from all over the world. It's a golden opportunity. An essential part of the work we do is to provide opportunities for meetings and encounters and conversations to begin."

In addition, there are smaller competitions, such as the Emirates Film Competition, and a host of smaller film and documentary clubs, allowing local residents the ability to interact with film, training institutions like the New York Film Academy, and film development funds like Sanad.

Probably the largest organisation is TwoFour54, a media production hub in Abu Dhabi. Through its various divisions, TwoFour54 provides training courses, production facilities and an industry fund for creative projects, including films. But the highlight is the creative community the organisation fosters, which allows new filmmakers to connect with others who have experienced the same challenges.

Out of this soil of interactions and exposure come ideas that then need logistical organisation to turn into reality. (It’s not called a film industry for nothing.)

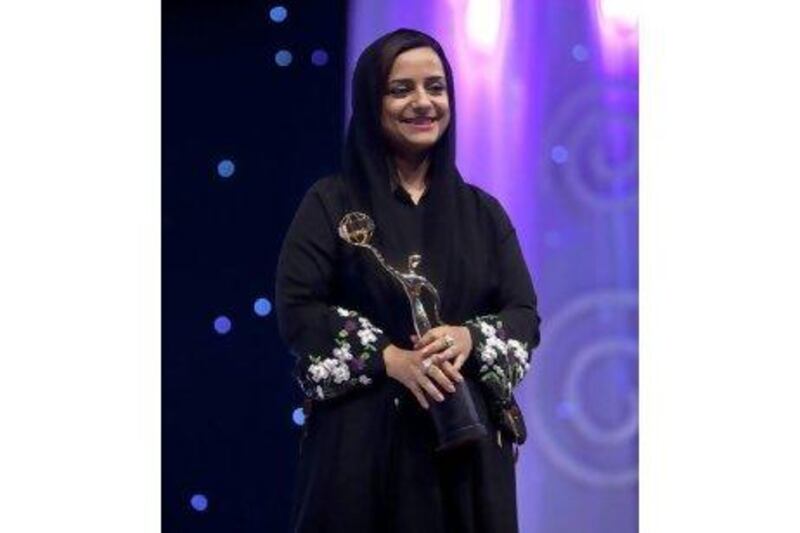

For Nayla Al Khaja, an Emirati filmmaker who made her first short film in 2004, finding those missing parts was tough.

“When I started my first film I asked – the biggest question everyone asks – where do I begin?” she says, “I didn’t know who to talk to. Simple things like taking approval to shoot on location – location approval services didn’t exist then, so you had to go literally to all the government departments, from the fire department, from the economic department. It was a big learning curve for me.”

Since then, Al Khaja has gone on to produce and direct more films, and was named the Best Emirati Filmmaker at the Dubai International Film Festival in 2007.

Even with that success and knowledge behind her, Al Khaja says she still faces cultural challenges, particularly as a woman.

“Acting is not perceived in our tradition as a respectable profession. It’s still taboo, especially for film, even more than television: film is seen as a mysterious underworld. It’s too sexy. There’s this image that if you want to be an actress in the film world you have to do some bad things – which is probably a stereotype, but based on true stories.

“There’s an element of exposure, which in our tradition is the complete opposite of what a woman should be. A woman should be conservative, should be protected, should be covered, not only literally but metaphorically. And film does the compete opposite: it exposes a woman to a large audience that could idealise her sexually or in a way that upsets our values. It’s something I struggle with on a daily basis.”

Al Khaja says she perseveres because of the importance of telling stories that matter to her. She is now working on her first feature film, based on a story from the UAE about exorcism.

Indeed, what is surprising when talking to Emiratis who aspire to make films is how often the idea of telling their own story in their own words emerges. It’s a convergence between decision-making at the government level – in choosing to create TwoFour54, for example – and desire at the grassroots.

In a series of interviews at TwoFour54, a number of filmmakers, from the Emirates, from Kuwait, from Egypt and elsewhere, some of whom were studying at TwoFour54 or were involved in the organisation’s extended creative community, spoke of their desire to impact a national conversation.

A common theme was expressed by Latifa Bin Ghannam, a student at the Cartoon Network Animation Academy at TwoFour54: “If you watch Japanese animation, it’s extremely popular. Because of the anime culture people are learning Japanese, they are learning stuff about the culture. And I was thinking, why not do that? If we can do something like that, but make it Arabic, people might be interested not only in the story but in the culture and they would want to learn Arabic as well.

“That’s what I’m aiming for, that they’d want to get to know us.”

Al Khaja agrees with this, explaining why it is so vital that stories of the region are told by the people of the region.

“It’s extremely important, because it’s grassroots. If it’s an Emirati story, then it should be told by an Emirati because they will know the details, the mannerisms, the cultural sensitivity, the accuracy. Because we’re not a very extrovert society.

“Emiratis keep to themselves. Because of that culture, even if you’ve been here all your life, you’d still not know the inside, because we don’t let people access us very much.”

As the Emirates and the wider Gulf develops, it becomes more pressing to tell the story of the region by and for the people of the region. Some themes can already be discerned, but, warns Al Khaja, “it’s too early to answer” what the dominant narrative will be. “It will be interesting to see what kind of feature films will be made in 10 years. After a whole collection of films, to see if there’s a thread that unites them all. It’s interesting because Emiratis are making them, so it will be interesting to see what’s the common denominator between all of them. If you ask me in five years I’ll probably have a better answer.”

Faisal Al Yafai is a columnist for the National. Follow on Twitter: @FaisalAlYafai