Michael Wadleigh's documentary Woodstock helped secure the event's image as the apex of hippy culture. Stephen Dalton speaks to the filmmaker about the festival and the 40th anniversary DVD Forty summers ago, a small group of young, long-haired American hippy capitalists were finalising their frantic plans to stage an ambitious outdoor music and arts festival in the idyllic countryside of upstate New York.

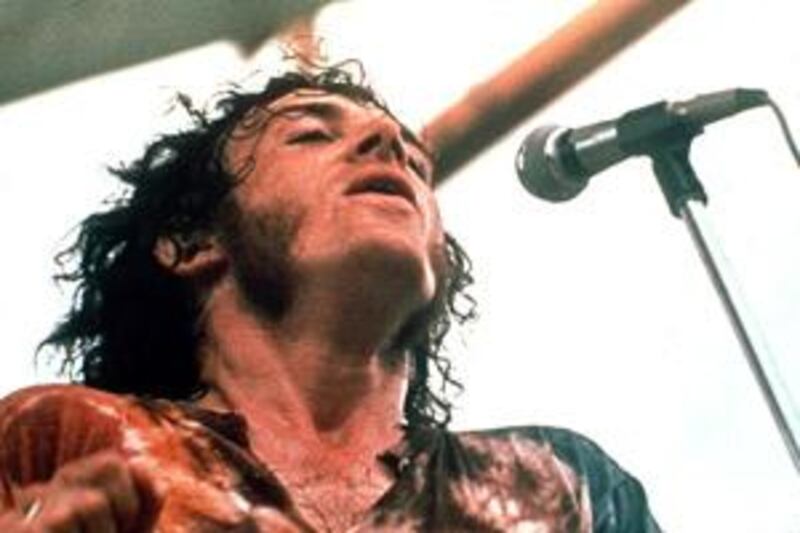

After months of legal and financial wrangling, including a last-minute change of venue, Woodstock was born. Billed as "three days of peace and music", the festival was scheduled for mid-August on Max Yasgur's rolling farmland, close to the sleepy town of Bethel. The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and Led Zeppelin all turned it down. But The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker, Joan Baez, Santana and dozens more signed on for the epochal event that would come to signify, for better or worse, the high watermark of hippy culture. Wisely, the organisers also decided to film it for posterity, recruiting the 26-year-old documentary maker Michael Wadleigh. It was arguably the smartest decision made in an otherwise fairly disastrous project.

The expanded 40th anniversary edition of Wadleigh's Woodstock film, newly released on DVD and Blu-Ray, is as much social document as music documentary. It offers a terrific, immersive, multi-screen journey through the festival from start to finish, cutting fluidly between performers, organisers and audience members. "What we discussed at the time was making it like Chaucer's Canterbury Tales," says Wadleigh, now 66 but still every inch the long-haired, soft-spoken hippy.

"We tried to make it not like a 1960s movie, but a sort of timeless tale. So you have the policeman's tale, the tavern keeper's tale, the nude bather's tale, the toilet cleaner's tale. We went for an elevated approach to the material because we were young intellectuals, I suppose. I think that's what makes it more than a rock movie. There's a sort of epic quality. You really feel like you are being transported to that environment."

Wadleigh's film also chronicles Woodstock's descent from bucolic idyll to rain-sodden, mud-slicked war zone. The organisers were simply not prepared for the huge crowds they attracted. They anticipated around 200,000 people, but half a million rock fans, freaks and flower children eventually converged on Bethel. On Friday afternoon, the makeshift ticket gates were overwhelmed and the fences trampled. By default, Woodstock became a free festival.

For Woodstock's organisers, flattened fences translated into huge losses. As Wadleigh recalls, the promoters fell into "deep depression" at this point. "When all the fences came down," he says, "and it became clear they were going to lose millions of dollars, they turned to me and said: 'You better do a good job, Wadleigh, or we're never going to get our money back'." The next three days were full of prickly negotiations and handshake deals. When The Who insisted on being paid in cash before playing, Woodstock's organisers had to rouse a local bank manager from his bed late on Saturday night. A massive rainstorm early on Sunday afternoon added to the deepening sense of chaos, turning the festival site into a mudbath and exposing live electrical cables.

"We had terrible problems with that storm," Wadleigh remembers. "It nearly electrocuted a number of people and destroyed several of our cameras. I've covered war zones - I've covered Darfur recently - and it was not unlike that... except at least in Darfur you can get a little sleep." One of Wadleigh's cameramen at Woodstock was an aspiring young filmmaker called Martin Scorsese, who later met his lifelong editing partner, Thelma Schoonmaker, when they worked together cutting Wadleigh's film. But the festival's rough, rugged conditions were clearly a challenge for this most urban of directors.

"You have to remember Marty was a complete unknown, and so he was treated as such," says Wadleigh. "Marty was not comfortable in the wilderness. He never was a hippy, but both Thelma and I were." Meanwhile, the strains of providing food, water and sanitation for half a million people began to bite. On Sunday morning, the New York state governor Nelson Rockefeller declared Woodstock a disaster area, threatening to send in the National Guard. In a deft bit of diplomacy, the organisers persuaded the governor's office to fly in medical teams and food supplies instead.

"Rockefeller wanted us shut down," Wadleigh says. "He wouldn't ship in any more film or more performers. Performers like John Lennon wanted to come up when he could see the way it was going - he told me that in person, but maybe he was flattering me." Woodstock ended with Hendrix playing a fiery, valedictory set to a half-empty field of stragglers as dawn broke on Monday morning. The legendary guitarist's historic torching of The Star Spangled Banner became a rock milestone, an inspired act of angry patriotism and anti-war protest.

"For years The Rolling Stones closed their shows with Hendrix playing The Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock," says Wadleigh. "Because, as Mick told me, you can't beat that for a political piece of music." There is extra Hendrix footage on the 40th anniversary DVD, alongside two extra hours of freshly restored performances from Creedence Clearwater Revival, Paul Butterfield, Grateful Dead and more.

"These are great musical performances by some legendary groups, so why not give them to people?" says Wadleigh. "It not only makes economic sense but musical sense. Especially when you go to YouTube, as I do, and you see such wretched coverage of groups. We've got great coverage of very famous groups." For some, Woodstock marked the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, a model of peaceful co-operation and blissful communion with nature. As Joan Baez later said: "For three days, people were almost forced to be kind to each other." Historians may mock the naive idealism behind the festival, but Wadleigh insists it was a strong political statement to hold a festival at that time, at the peak of national division and anger against the Vietnam War.

"That's how Woodstock got its name as a hotbed of radicals," he says. "Musicians and artists arrived, but radicals like Allen Ginsberg, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan all lived up in Woodstock at one time or another. Just look at the festival's famous logo, the dove of peace sitting on a guitar. The title was 'three days of peace and music', and that's what they promoted. They took pains to get not just bubblegum singers but musicians who sang songs of real content."

But for others who attended, Woodstock actually killed off 1960s radicalism. The Rolling Stone writer David Dalton was there and later savaged the festival as "a hippy Disneyland, a triumph of public relations and old-fashioned merchandising". To dissenters like Dalton, Woodstock's organisers were essentially profiteering from hippy culture. Michael Lang, one of the festival's founders, laughs at this idea. "If that were true, we weren't very good at it," he says.

Sure enough, Woodstock was a financial disaster. It took 11 years for the company behind it to turn a profit. Yet, 40 years on, the festival is remembered as a significant cultural landmark partly because of Wadleigh's documentary and its accompanying soundtrack album. Both became unexpected smash hits, and reportedly saved Warner Bros from bankruptcy. "Rock films had no track record of making money," Wadleigh says. "Warner Bros didn't think we were going to make any money at all, but then it went on to break all records."

But before Woodstock could even be released to Oscar-winning glory, Wadleigh had to battle to prevent the studio from tampering with his marathon four-hour edit. He eventually resorted to stealing the film's audio tracks and negatives, then threatening to set himself and the film on fire if they would not back down. "They leaned on me very hard to put in some other Warners acts," he says. "But I had a final cut contract. Everybody I wanted, I got. Everybody I didn't want, out they went."

Every major pop festival since Woodstock, from Glastonbury to Live Aid, owes a little debt to that landmark gathering in August 1969. Later events staged under the official Woodstock banner, however, became more infamous for rowdy crowds and commercial sponsorship than peace and love. The most notorious was the 30th anniversary festival in 1999, held on a former US Air Force base, which was married by riots, arson, looting and violence.

"The problem was there was little excuse for the other festivals except to make a buck," says Wadleigh. "They delivered none of the content, and the site they got was just very uncomfortable - big fences, like Guantanamo Bay or something. When you put in a festival like that, how can you even call it Woodstock?" Wadleigh's own story has taken several turns since Woodstock. Despite his early success, he went on to make a surprisingly small body of films, peaking with the 1981 sci-fi werewolf thriller Wolfen. Wadleigh then left Hollywood feeling creatively stifled but financially comfortable, thanks to $2 million (Dh7.3m) paycheques for incomplete projects.

Together with his wife, Birgit Van Munster, Wadleigh is now heavily involved in sustainable development issues. The duo frequently appear at universities and conferences around the globe with their Homo Sapiens Project, a lecture in the form of a graphic novel told from the viewpoint of an alien visiting Earth in the far future. "There is a real connection with Woodstock and what I'm doing now," says Wadleigh. "The 1960s in America became known as the Woodstock Generation, after the festival and after my movie's version of the festival. The ecology movement got off the ground then. So did the anti-war and human rights movements, Martin Luther King Jr, Bobby Kennedy - a lot of things that are still with us, including sustainable development."

After a long spell in Tanzania, Wadleigh and his family recently relocated to Britain. They now share a farm in the rolling hills of West Wales, surrounded by the peaceful wonder of nature. Forty years later, he is still living the Woodstock dream.