Viola Shafik grew up between Egypt and Germany – she has a parent from each country – and describes herself as bi-national. "I don't like the term bi-cultural or multicultural because I don't see the cultures as so different," she said at last month's Berlin International Film Festival, where her film Arij – Scent of Revolution had its world premiere.

Germany's pre-eminent scholar of Arab film, Shafik is also the author of Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. First published in 1998, it has become the indispensable touchstone for students studying the rich heritage of Arab movies.

Arij – Scent of Revolution is the latest contribution to the growing body of works affected by the events in Tahrir Square in 2011, which were the subject of the documentary The Square. As with The Square, which is also by a female director, Jehane Noujaim, and had a big festival debut, and Sherief Elkatsha's movie Cairo Drive, Shafik began by making an entirely different film that changed course during production, as the foundations of Egyptian society were rattled by the removal of Hosni Mubarak.

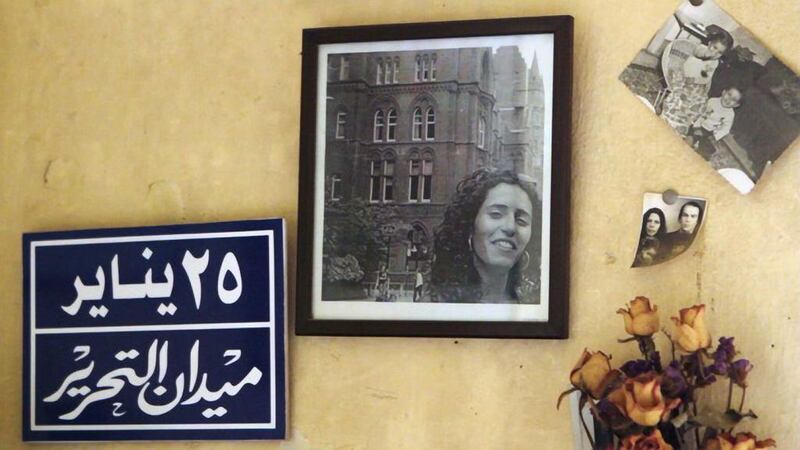

The idea for Arij originated while Shafik was making Journey of a Queen, which was released in 2003. "I made a film about a small Egyptian artefact, a small portrait of a queen, Tiye, the mother of Akhenaten, which travelled to Germany under the pretext that the work of art was being saved," she recalls. "The film was about the competition between European colonial countries to grab as many artefacts as possible. It was while in Luxor that I found the shop featured in Scent of Revolution and discovered the photographer Atta Gaddis."

Shafik was initially astonished to discover that one of the first photographers working in Egypt was inspired to study Luxor rather than Cairo. “It makes sense because of all the monuments there, but then you have to question where did he get the technique and know how to discover such beautiful photographs.”

Shafik was also struck by how different from today Luxor was in the 1850s and at the turn of the 19th century. The idea was to make a documentary that detailed this investigation. “We have my own narrative, which is my own search for history. Then there’s the visual mystery of the photograph in the context of colonisation and national identity.”

She continues: “Going back in history means dealing with two revolutions. First, the 1952 coup that became a revolution was more of a revolution than the rebellion that happened in the last three years. Today we have a revolution that comes from below but so far there has been no change to the system.”

Shafik began filming in 2010, but the story was overtaken by events taking place in Cairo. These led to what she charmingly calls the introduction of “interfering narrators”. The film was no longer just her investigation into how a city was changing.

The documentary moves its focus onto four protagonists – Alaa El Dib, Awatef Mahmoud, Francis Amin Mohareb and Safwat Samaan – who all use different types of media to try to understand the society in which they live.

"I put the novel Lemon Blossoms [set in the aftermath of 1952] in the foreground because the author El Dib is the oldest. And as such he can sort of have the benefit of being the wise man telling me the story, even if his novel is full of depression and telling us that change will not happen," she says.

“The other three are more positive. The collector who keeps all these items and works in the photography museum, which is something for the future, the activist who uses videos for change and the young girl who creates a virtual universe online.”

Entwined together in this way, the protagonists give a good picture of how the hope of February 2011 has inspired some to dream.

[ artslife@thenational.ae ]