Artists in Kashmir are sustaining craft and artistic tradition despite the long-term conflict and increasing economic difficulties that threaten their trade. Working in Srinigar's cottage industries and workshops are craftsmen determined to preserve centuries-old production and artistic techniques found only in Kashmir. "Much great art exists in Kashmir," artist Shafi Siraj says, "and it is unique - a combination of Islamic influence and traditional Kashmiri artistry that you will only find here."

But, Siraj continues: "It is harder now to keep artists employed, and pass on skills, because there is less demand." Instability in the region has dissuaded many tourists from visiting and spending their money on handicrafts, while conflict over the region between India and Pakistan has prevented exports and reduced supplies of the necessary materials. Despite this, traditional Kashmiri craftwork is still being produced.

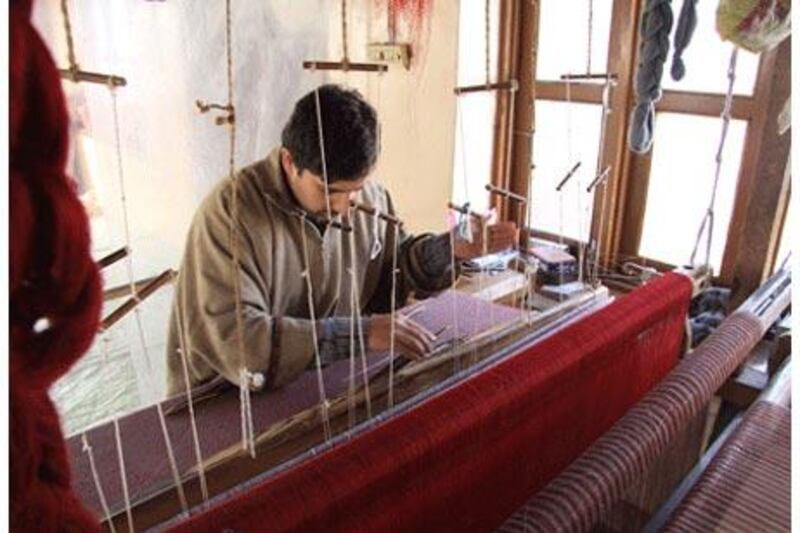

Cottage industries across Srinigar have continued to produce unique art and textiles including finely woven pashmina shawls, hand-embroidered fabrics, silverwork, carpets and wood carvings. Firdoz Ahmed and Muhammad Rafik work on the top floor of a traditional wooden Kashmiri house, weaving pashmina fabrics on hand-operated looms. It is a painstaking process. Hand-spun wool is dyed and then loaded onto wooden looms, a complex threading process that takes up to a day and a half to finish. Weavers produce 10-13cm of fabric a day.

Despite mechanised looms increasingly being used by some manufacturers because of the greater volume of work they can produce, Rafik says in order to produce traditional products, traditional methods are key. "You cannot produce the quality of fabric that we do by hand with a machine. We can check continually for flaws, weave tighter and stronger pashmina, and cut threads properly." "We have always produced fabric in this way - without Kashmiri materials or production, you cannot make true Kashmiri products."

Even in the face of copycat art emporiums across the region, and throughout India, Kashmiri artists maintain that the best way to sustain traditional artwork is to maintain the practices that produce it. Ahmed says: "Large manufacturers use wool instead of pashmina, or use machines to produce woodcarvings - it's cheaper and it sells, but if we don't use Kashmiri materials and traditional artwork, we'll lose a large part of our heritage and identity".

In a bid to achieve this artists are increasingly exporting their work, and establishing emporiums dedicated to selling only genuine products. On the city's Dal Lake, home of Srinigar's famous houseboat community, floating markets stock artwork produced by rural communities in Kashmir in favour of mass-produced art. Independent traders make their way over the lake with silver bracelets and hand-stitched bags balanced on tiny shikara rafts.

Moazzem Babloo says the money he makes from selling turquoise-encrusted jewellery goes directly to Kashmiri villages. "This is true Kashmiri art, not copies from India. This is how people in the countryside support themselves, and keep their traditions. Families teach their children, they pass on the skills." Youth involvement in the arts is seen by many here as key to preserving and maintaining a strong artistic emphasis in Kashmir.

The best place to see artists at work is in the Old City, where family-run cottage industries and workshops are striving to support traditional art despite the circumstances. Above a narrow street is Abdul Khan's tiny embroidery shop. Three men seated on the floor first draw, and then embroider intricate patterns on shirts, scarves and bedding, spinning wool from hand-held looms and continually adapting designs and colour schemes for their clients.

Khan explains demand from Srinigar's residents is steady. He says: "We take a lot of work, and it is all hand-stitched. Stitching a design on a shirt can take between one and four days; it depends on the patterns used." Despite the cost, Khan has established workshops in the surrounding countryside to handle demand and also to offer as well as develop a greater range of embroidery techniques. "We're supporting embroidery traditions, and also encouraging them by employing as many people from different areas as we can. It keeps our work fresh and also means we don't lose certain designs or rural styles."

Shafi Siraj also moved some of his workshops out to the countryside. He sells coats and bags made of suede and leather embroidered with traditional Kashmiri patterns. "I employed almost 40 people in one of my workshops, but over the last few years that number has fallen to five. We have faced a lot of export embargoes and we couldn't get enough materials to work. I had to tell my European clients not to send orders because I knew I couldn't fulfil them. It became too expensive to run the business in Srinigar."

His fur-lined coats have made a particular impression on tourists, and Siraj exports made-to-measure garments around the world. Siraj continues: "Now though, I'm using workers in the countryside to stitch my products and add embroidery, and also to supply the leather we use. I've established new clients in Asia and the United States, based on the quality and authenticity of the work I'm producing. You couldn't use a machine, or a workshop abroad to produce this work."

At Qadir Najar's carpentry workshop, artists are employed to carve and sculpt traditional Kashmiri patterns into the furniture the workshop produces. He insists on handcrafted products, and the carpenters in his workshops carve heavy walnut panels with hand tools. Najar says: "Employment here has fallen, but at least we have some workers still here. I can't use machines; we adapt traditional patterns here, and use the tools and techniques that are traditional to Kashmiri work."

In a bid to sustain the workshop, Najar focuses on the traditional, and has won international clients by producing what he terms "true" Kashmiri design. "It is hard, against big manufacturers who copy Kashmiri design, and because not many tourists come now. But our work is so important because Kashmiri art is only found in Kashmir. So if we use our traditional techniques, we preserve our traditional arts."

The passion for the arts extends beyond handicrafts. Last week, Srinigar's third International Film Festival, run by the Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, showcased three days of short films produced by emerging filmmakers in the region. Hira Narjaf teaches classical dance and singing and says young people are keen to learn. "We have so many traditional dances: Geetruu is a rural folk dance for parties and weddings; Bakhan folk songs depict our daily life in Kashmir; Ladishah you can say is our humour, our satirical singing and comment - and these are all important."

"They are passed on through schools and families and lessons before festivals - people here are very proud to be Kashmiri. We are utterly different in our culture, and people take time to preserve it."