The writings of Andalusian Sufi mystic and philosopher Ibn Arabi consume Elias Zayat’s octogenarian mind.

"I don't know how his work will reflect in my art," says the Syrian master, 80, whose solo show, After the Deluge, is running at Dubai's Green Art Gallery. "But I have a feeling it's going to take me back to abstraction."

Sufist thought, Byzantine heritage and Christian iconography continue to influence Zayat’s practice. After studying for degrees in fine art and art restoration in Sofia, Cairo and Budapest, he returned to Damascus in the mid-1970s and became part of a pioneering group of artists, including late masters Fateh Moudarres, Louay Kayali and Mahmoud Hammad, who established the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Damascus.

Zayat taught for more than two decades, retiring in 2000 to focus on his art. Still living and painting in Damascus, he is archiving his work in preparation for a 2016 Skira-published monograph edited by art historian Salwa Mikdadi.

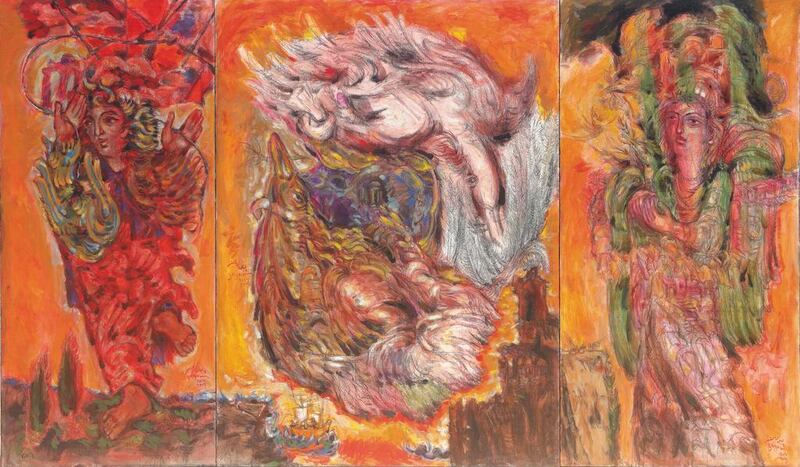

After The Deluge, a 13-piece exhibition, is a sequel to the exhibition of paintings shown this year at Art Dubai through Atassi Gallery. From a historically rich Syria to a country now ravaged by war, Zayat takes viewers on a journey that begins in the ancient city of Palmyra, where ISIS has destroyed some of the region's – and world's – most cherished cultural sites.

“I don’t want to go back to Syria if they’re going to destroy it all,” Zayat says.

The world looks infernal in these works. It may even look like Dante’s Purgatory – yet you believe there is hope?

I’m looking for lost hope. We are still in a mess, in utter destruction. There are symbols of peace here and there, but the black bird in some is questionable – is he a symbol of peace? And what is an animal’s skull doing underneath it?

If these works are indeed purgatorial, how did it feel to paint them?

I feel better when I paint. If I didn’t ... I think that would be madness. And I’m not done yet.

You mentioned that you would like the works presented at Art Dubai to be considered one work and After The Deluge another. Each painting has its own beginning and end. That’s very multilayered.

That's precisely my mental make-up. I think in pictures. This is my language – I speak in form, colour, line and the picture's architecture. These figures are based on everything I've ever read and seen. Both shows explain and complete each other. With After The Deluge, I see what the future holds. The deluge that I'm seeing repeats the creation of the world. I see peace. Art, after all, is a look into the future.

How often did you visit Palmyra?

As often as I could. I’d even go to the museums to see the relics. It was never enough.

What attracted you to restoration?

It means making a discovery that is otherwise unknown. I learnt and practised restoration to learn about materials. I think all artists must understand the materials with which they work.

You also enjoyed discovering the treasures and history of your country and the Arab world.

Everything I’ve done in my life stems from my attachment to my country. My family has been in Damascus for at least three generations and this initially inspired me to discover my roots and relationships tied to Syria and the Levant. With these paintings, I’m telling you that this is where I am from.

You studied in Europe and the Arab world. What were those experiences like?

Cairo was beautiful and I travelled all over Egypt. I can say that my time there impacted my work. I had a tendency for French Impressionist art, which I actually found in Egypt. Impressionist masters were not a focus in Bulgaria – my professors in Budapest were advocates of 19th-century German realism, but Hungary is where I studied and understood art history.

You returned to Damascus with a pioneering spirit and contributed to the foundation of the Faculty of Fine Art.

At the time, art for the public was concerned with a picture, not a way of thinking. Journalism played a role, as did literature, but visual art wasn’t as encouraged. The government built the university, helped some artists, bought a few works, but the art scene progressed on its own. My peers were unique individuals – we’d debate, gather and congregate at the Faculty, which we built. We taught the youth and were ecstatic when the first batch of students graduated.

How has your work evolved?

At first, I focused on Impressionism and even 18th-century art, whereas now I want to express a thought. This is more difficult, especially when one has accumulated all this knowledge, read what all these artists have written and seen their work. The truth is, in art there is no before or after. For example, I started with abstraction but then abandoned it from the 1960s until the 1970s, and went back to figurative art. It was constructive abstraction. Now I want to go back to abstraction but not in a constructivist form.

• After The Deluge runs at Green Art Gallery until November 4, Saturday-Thursday from 10am-7pm, Al Quoz 1, Street 8, Alserkal Avenue. Visit www.gagallery.com

artslife@thenational.ae