Donald Trump might consider himself a king among men, having secured the Republican nomination for this year’s US presidential election, but he antagonised rock royalty along the way – the British band Queen, that is.

Trump marched onstage last week to the sound of the band's classic hit We Are the Champions, which resulted in angry complaints from fans, given that Trump's comments about women, Mexicans and various minorities, including Muslims, have sparked outrage during the campaign for the Republican Party nomination.

“This is not the kind of thing we want to see our music supporting,” wrote one disgruntled fan – and Queen guitarist Brian May agreed.

“I will make sure we take what steps we can to dissociate ourselves from Donald Trump’s unsavoury campaign,” he wrote on his website.

Of course, the relationship between politics and popular music has often been tricky and Trump is simply the latest chapter in the story. Indeed, a new rock/rap supergroup has assembled to challenge him. The Prophets of Rage – which features members of Rage Against the Machine, Public Enemy and Cypress Hill – is “an elite task force of revolutionary musicians”, according to Rage’s Tom Morillo. They plan to target the Republican convention in Cleveland next month.

Meanwhile, Queen are not the only big-hitters Trump has annoyed by using their music. Last year, he infuriated the actively liberal members of REM by using It's the End of the World As We Know It.

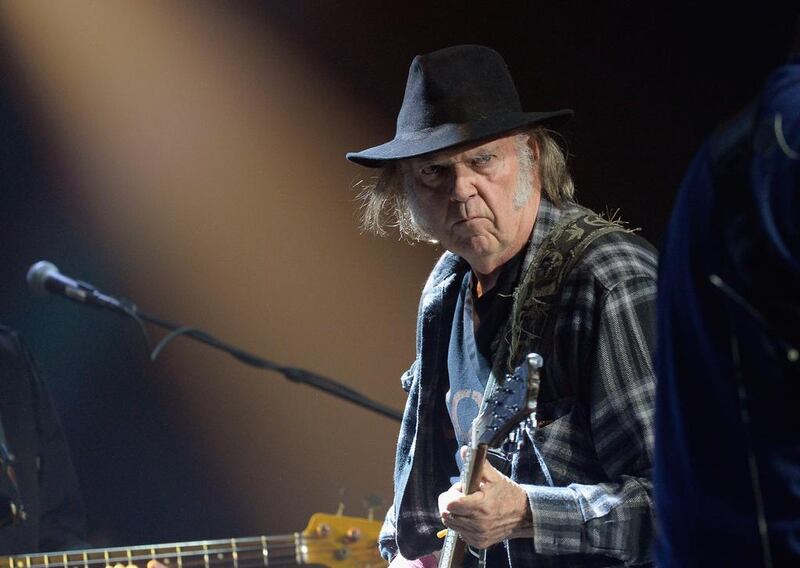

More intriguing, though, is Trump’s row with rock legend Neil Young.

Young ploughs an unpredictable political furrow. In the early 1970s he wrote magnificent songs railing against the status quo in the United States – but then horrified his hippie fans by supporting the policies of two right-wing presidents: Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, then George W Bush after the September 11 attacks in 2001.

In between, he released another mighty protest record – 1989's Keep on Rockin' in the Free World – which was targeted at the first President Bush's regime. So when Trump "songjacked" that anthem, the Canadian singer, having not been asked for permission, wrote an angry response.

“I would have said no,” he wrote. “I don’t like the current political system in the US and some other countries. Increasingly, democracy has been hijacked by corporate interests.”

Unfortunately, his righteous rant was undermined somewhat when a photograph surfaced of the two men together – Young had asked Trump to help fund his iTunes-like service, Pono.

A year later, the singer seemed more cool about Trump using his songs. “I got nothing against him,” he said, while backing one of Trump’s presidential rivals, the Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders.

Rock stars still get political, if not always so polemical. The increasingly hostile hot topic in the United Kingdom right now is whether Britain should leave the European Union, with a referendum looming on June 23.

Supporting the leave campaign, slightly curiously, is another Canadian rocker: Bryan Adams. But bringing genuine harmony to the debate is Gruff Rhys, the frontman of Super Furry Animals. His song I Love EU is as romantic as any regular ballad: "From the Danube to the Severn and the Seine, you're driving me insane..."

The times, they are a-changing. As they always do, particularly in the world of music. Rock ‘n’ roll was widely regarded as a bad influence until the 1960s, when shrewd leaders – such as Labour prime minister Harold Wilson – realised the PR benefits of being photographed with, say, The Beatles.

President Nixon's 1970 meeting with Elvis Presley was so momentous – Elvis asked to become an undercover agent – that it is the subject of a feature film. Elvis & Nixon, starring Kevin Spacey as the US president and Michael Shannon as The King, is due to be released in the UAE on June 30.

Rock stars have become much less reverential since then. In the UK, the divisive leadership of Margaret Thatcher inspired a huge musical protest movement, Red Wedge, featuring the likes of Paul Weller – although it had little electoral effect.

More successful was last year’s Canadian campaign, #ImagineOct20th, in which musicians, including Feist, galvanised younger voters and helped end the lengthy reign of prime minister Stephen Harper.

Consciously courting musicians can backfire. Ronald Reagan's aides attempted to enlist Bruce Springsteen's support during the 1984 election campaign, having assumed that Born in the USA was a patriotic anthem – it is the opposite, which hardly helped Reagan's image.

Inspired by Britpop, the newly elected Tony Blair invited Oasis star Noel Gallagher, and other musicians, to Downing Street in 1997 – but Blur’s Damon Albarn publicly refused the invitation.

And in 2010, when Conservative prime minister David Cameron praised the music of indie legends The Smiths, guitarist Johnny Marr responded: “I forbid you to like it.”

Music and politics can work in perfect harmony, however. Barack Obama welcomed rapper Kendrick Lamarr to the White House in January, and both seemed pretty impressed.

Now Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic nominee for this year's presidential election, is following suit, lauding Beyoncé's visual, adultery-themed album Lemonade, and jokily nominating her for vice president. Clinton understands music's positive political power – in 1992, her husband, Bill, won the presidency after playing saxophone on talk shows and then persuaded Fleetwood Mac to reform for his inauguration.

Sometimes the worlds of politics and pop music genuinely mesh. Blur drummer Dave Rowntree, who recently played in Dubai, has stood in several elections for Britain’s Labour Party.

And one president who really knows his music is Estonia's Toomas Hendrik Ilves, who released Teenage Wasteland last December, a compilation of his favourite songs, featuring David Bowie, The Ramones and Roxy Music.

That proved popular enough that Ilves has now turned to DJing. Well, in such a precarious business as politics, it’s good to have another career to fall back on if it all goes wrong.

arts@thenational.ae