Seven years ago, the Arabist and translator Bruce Fudge set off in hope rather than expectation when he went in search of the collection of wondrous tales known as A Hundred and One Nights.

Fudge was living in Morocco at the time and as he searched the bookshops of Fez and Meknes for the marvellous tales of love and adventure, hidden treasure, djinns and death, his enquiries were met with the same and all too predictable reply.

"They'd never heard of it," he says. "I went around all the bookshops and without exception they said, 'Don't you mean A Thousand and One Nights?'"

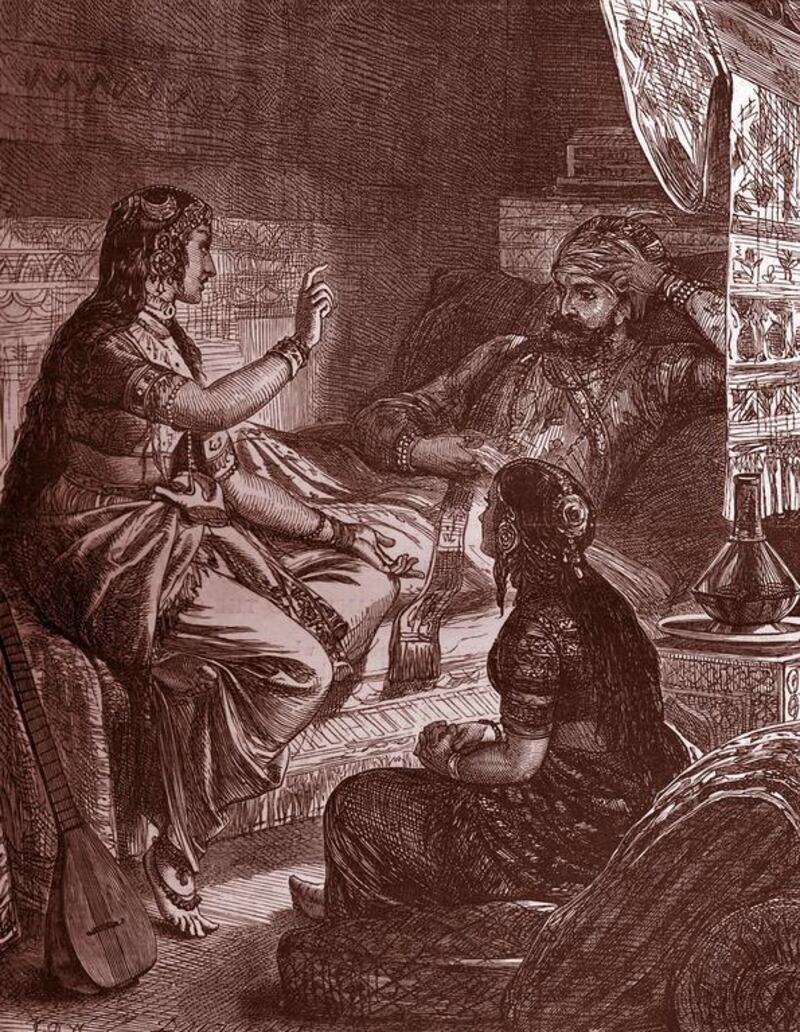

Despite featuring familiar characters such as the story-telling Scheherazade, Harun Al Rashid and the famously cuckolded and homicidal kings Shahryar and Shahzaman, the booksellers’ ignorance came as little surprise to Fudge.

The first printed Arabic edition of A Hundred and One Nights was only published in 1979 and even though the seven surviving manuscripts are all written in a Maghribi script that originate in North Africa, the tales were not widely read, even in the countries of the Maghreb. "It's not that well known in the Arab world, but then again pre-modern literature isn't particularly well known in any country," admits the academic, who is now professor of Arabic at the University of Geneva.

Fudge had never seen any of the manuscripts, two of which are held in Tunis, and three of which now belong to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, but he had read part of a French translation that convinced him that the tales were rather more than a condensed version of A Thousand and One Nights.

Translated as Les Cent et Une Nuits, the very first printed edition of A Hundred and One Nights was published in Paris in 1911 and until the appearance of the first Arabic edition, which was edited by the Tunisian scholar Mahmud Tarshunah in 1979, it was the only printed version of the tales in existence.

Apart from sharing certain characters and stories, such as The Ebony Horse and The Prince and the Seven Viziers with its more illustrious literary cousin, Fudge insists that A Hundred and One Nights also contains important narrative differences that raise interesting questions about how themes and motifs throughout the Night's corpus may have been developed and transmitted.

“It’s fair to say that this is a North African collection because all of the known manuscripts originate from there and they are all written in a North African script and there is also almost no trace of the tales in the Eastern Arab world, but that doesn’t tell us where the stories originated.”

Fudge refuses to jump to conclusions about the stories' origin or their age and is sceptical of the claim, made by the tales' German translator, the Orientalist, translator and musician Claudia Ott, that A Hundred and One Nights might be Andalusian in origin and date from the 13th century.

Ott's translation of A Hundred and One Nights, first appeared in German in 2012 thanks to an episode that would fit neatly alongside a Night's tale.

In 2010 Ott, who had already spent several years translating the oldest surviving version of A Thousand and One Nights, discovered a previously overlooked manuscript at the opening of an exhibition, Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin where she had been asked to perform as a musician.

Browsing the show, Ott found the manuscript in a glass cabinet with art objects from Andalusia. It had been bound into a single volume alongside a geographical treatise by a certain al-Zuhri which had a colophon that dated the treatise to 632 Hijra, the equivalent of 1234 or 1235 in the Gregorian calendar, but did not refer to the tales.

“The binding is modern and there is a rupture between the two works,” Fudge explains in his own edition and translation, which was published this week as part of the Library of Arabic Literature, an ambitious collaboration between New York University Press and NYU Abu Dhabi that aims to produce Arabic editions and English translations of significant works of Arabic literature.

"The pages of the Nights have been restored and Al Zuhri's work not. Although there are some similarities in the script, there is little reason to assume the same scribe and date."

Until the mid-20th century it was widely presumed that the tales we now associate with the Nights – of Scheherazade, Aladdin, Ali Baba and the roc, the giant legendary bird that carried off elephants and other large beasts for food – were likely to have originated in the 14th or 15th centuries.

That view changed, however, in 1948 when Nabia Abbott, the first woman faculty member of the Oriental Institute at The University of Chicago, discovered a rare piece of early medieval paper that contained a passage from A Thousand and One Nights.

Thanks to her careful analysis of the other texts written on the same document – a few scribbled phrases, a legal attestation to a contract and a draft of a personal letter – Abbott was able to date the passage to the early 9th century.

That discovery, which pushed Scheherazade’s literary origins back at least 1,100 years, caused a literary sensation at the time and secured Abbott a place in the history of the Nights.

The first textual mention of A Hundred and One Nights is found much later, in a 17th century catalogue from Istanbul, and of the manuscripts which can be dated with confidence the oldest was written in 1776.

But thanks to the peculiarities of the Sharyar/Shahzaman/Scheherazade story in two of the surviving manuscripts – what scholars refer to as the Nights' "frame tale" – it is possible that A Hundred and One Nights may pre-date the oldest version that is found in its more famous counterpart.

"Scholars have been interested in the frame tale of A Hundred and One Nights because it seems to reflect an earlier, South Asian version of tale that was thought to be the origin of the frame tale in A Thousand and One Nights," Fudge explains.

In this alternate retelling Sharyar and Shahzaman, the kings whose cuckolding eventually leads to the executions that inspire Scheherazade’s nightly tales, are brought together by an annual beauty contest whose details, to the general reader, are strangely reminiscent of the tale of Snow White.

In the story, a king looks in a mirror and demands to know if there is anybody in the world more beautiful than he and when one of his subjects says that there is, an Indian youth called Zahr al-Basatin (Flower of the Gardens), the king demands proof and summons the young man to visit him in his court.

In the process of their eventual meeting, the king and the youth both uncover the infidelities of their respective wives and with that discovery the familiar story of the Nights begins.

Fudge argues that the beauty contest represents a more convincing narrative than the version told in A Thousand and One Nights, where King Sharyar suddenly decides that he wants to see his younger brother, King Shahzaman, and summons him to his court.

As scholars have long pointed out, the narrative in A Hundred and One Nights also recalls a far earlier Chinese-Sanskrit version of the tale.

When it comes to dating the different versions of the frame tale, there is also the question of Sheherazade’s sister, Dunyazade.

In A Thousand and One Nights Dunyazade's role seems peripheral as she merely provides the prompt that allows Scheherazade to begin her tales, but in two of the manuscripts of A Hundred and One Nights, it is Dunyazade who sleeps with the king and Scheherazade who narrates.

“Often when you look at the transmission and transformation of stories you can find characters that don’t really fit or seem to have lost their purpose and that’s often a sign that something has dropped out of a story or changed,” Fudge explains.

“It is more likely that a character will lose their original importance than an unimportant character will suddenly gain a larger role so if you are dealing with a version where she still has that function it’s quite possibly the earlier version of the tale.”

If the peculiarities of A Hundred and One Nights' frame tale and its versions of The Ebony Horse and The Prince and the Seven Viziers point to older, eastern stories which must have passed through the Middle East on their way to North Africa, the details of that journey remain a mystery.

"There is no evidence of any Middle Eastern manuscripts of A Hundred and One Nights or any North African manuscripts of A Thousand and One Nights and yet they both come from a common source," explains Fudge.

If the 101 Nights raises more questions than it answers about the age and origins of the Nights, its value in opening up a new window on what Fudge describes as a largely neglected field of Arabic literature is crucial to the academic.

“The sharing of the motifs shows that the development of the Nights is probably more complex even than we thought as many of the stories have older or analogous versions in eastern manuscripts, but this is also another step in opening up a huge body of Arabic literature that has not been well known,” the academic says.

"Until now, the Nights have always been treated as an aside, they're not considered a part of the classical Arabic literary tradition, but I think that's unjust and does not give a clear picture of the real situation," he insists.

“There are actually many many story collections like the Nights from the pre-modern Arab world, libraries in Europe and the Middle East contain untold numbers of neglected manuscripts, but almost everything we know about pre-modern Arab literature comes from the ulema, the scholarly class of the litterateur or religious scholars who were largely writing to and for each other.

“What we have here is Arabs telling each other stories and a side of Arab literary life that we don’t know so much about but that is much more accessible.”

That accessibility is central to Fudge's translation of A Hundred and One Nights into English as well as his new edition of the original Arabic text. His aim, he insists, is to bring the literature to a wider audience and with its concise collection of 18 tales, most of which are new to us, and clearer, more convincing narratives, A Hundred and One Nights has every chance of success.

"When people talk about pre-modern Arabic literature, I would like these works to be a part of the conversation. The two best known works of Arabic literature are A Thousand and One Nights and the Quran," Fudge admits, "but one is better known in translation than in the original and the other is considered untranslatable".

Nick Leech is a feature writer at The National.