In the great European immigration crisis, in which Europeans’ right to refuse entry to foreigners has for years been allowed to trump foreigners’ right to life, perhaps no contention is more unshakeable, and more false, than the idea that there are good and bad migrants.

Good migrants are said to be refugees, people fleeing persecution and war whose suffering legally obligates European countries to accept them. (Although not all persecution and not all wars. The past week’s outpouring of western concern focuses on Syrians; Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, and the Rohingyas of Myanmar are forgotten.) Bad migrants are everyone else: those who also dream of a better life but who, because they did not face imminent death when they set out, are deemed to have done so unjustifiably. The usual term for these troublesome travellers is “economic migrants”. The phrase is intended as a pejorative that exposes the greed driving the foreign swarm.

In this myopic and deadly parochialism, a few home truths are being forgotten or ignored. There is the awkward historic truth – one in which the Africans arriving in Europe are often quick to remind their reluctant receivers – that much of Europe’s wealth was built by rapacious European economic migrants who made their fortunes in Africa in colonial times. And there are a few equally uncomfortable present-day ones, such as the way that the wish to keep undesirables out has boosted undesirables at home – like the Italian Mafia, which has amassed hundreds of millions of euros by rigging contracts to house, feed and educate the new arrivals in migrant centres. Or that in most European countries, the number of foreigners pitching up is more or less balanced by the number of native citizens who, facing none of the same restrictions on migrants from poorer parts of the world, have moved overseas. (For example, about 4 million Britons live outside Europe, compared with the 4.76 million non-Europeans who live in the UK.)

Perhaps the boldest lie of all is that economic migrants, who are mostly from Africa, are all escaping destitution and have decided that Europe’s social welfare system is their best ladder out of it. To test this idea, let’s rewind to the paradox mentioned earlier – how Europe’s immigration crisis has boosted the Italian Mafia. Prohibition, on any thing, tends to open opportunity for criminals, who discover that when the law drastically restricts supply but leaves demand untouched, they can charge a fortune for it. So it is that Europe’s battle against migrants has also been great for African, Middle Eastern and Asian criminal syndicates, which are making billions of dollars a year from people trafficking. The typical cost of a trip to northern Europe from a central African country like, say, Nigeria or Sudan, across the Sahara, then across the Mediterranean, then up the map of Europe is about US$5,000 to $10,000 per head. People smugglers operating in Libya wire-tapped by Italian anti-mafia police offer different prices for different levels of service: a fast or slow truck across the desert, above or below deck across the sea, or even, for the top price, a flight and a visa bought from a corrupt European diplomat.

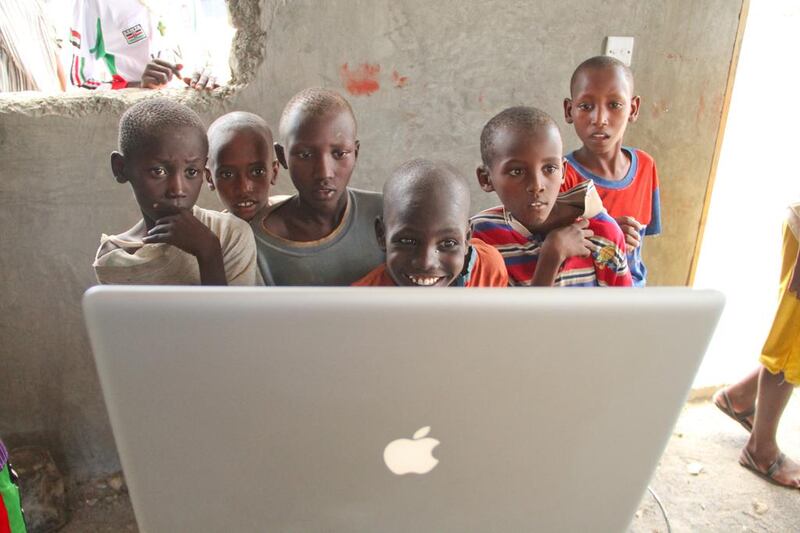

Even the cheapest passage is about 10 times what it costs a European to travel legally the other way. What’s really interesting about that is not so much the unfairness but the fact that millions of people from a continent supposedly mired in poverty are able to afford it. In southern Europe’s migrant centres, about half the residents – generally Syrians, Iraqis, Afghans and Eritreans – are refugees, but the other half are Africans from countries not at war nor politically repressed. Talking to Nigerian, Senegalese and Gambian migrants this April in Sicily, most were young middle class men, fluent in English. A good proportion were educated to degree level.

Imagine the grit and ambition of someone who has left his family and all his prospects and paid thousands of dollars to cross the desert and the sea in great hardship to pursue a dream. These, actually, are the kind of migrants every country should want. Since early humans first left Africa in search of fresh pastures, migration has been a primary driver of human advancement. Migrants are self-starters, visionaries and builders of nations. That is as true today as ever. Many successful economies in the world – look at the US, Germany and Britain; look at Singapore, Monaco or Dubai – have high immigrant and migrant populations.

And generally, this economic migration is considered an economic good. There are 230 million migrants in the world, and while a quarter of those are refugees, three quarters of them are the kind of movers and shakers – such as high-paid creatives, bankers, industrialists and engineers, or the equally essential labourers, such as truckers, assembly-line workers or farm pickers – that everybody wants.

The problem with African economic migrants, then, is one of perception.

To many in Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa is still a land of babies with flies in their eyes whose migrants can only be a burden. That is to overlook another gathering truth. After an age in which disease and slavery long kept Africa a vast and empty land, it is now becoming a vast and crowded one. As a result, those great engines of human progress – private property, communication and cities – are becoming the norm, and Africa is quickly getting richer.

The annual economic growth of the continent’s countries excluding the five North African states, has been double the world average since 2003 and, in most years, they account for half or more of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies, with some expanding 20 per cent or more in a year. Millions of Africans are pulling themselves out of poverty – about 400 million will do so between 1990 and 2030, according to UN and World Bank projections. Zambia for example, although still leaning on its copper resources, introduced economic reforms during the 1990s and is now one of Africa’s most urbanised countries. Unemployment and the Aids crisis remain critical problems, but its economy has diversified into tourism and services. Social indicators, such as life expectancy and infant mortality rates, are improving.

Outsiders find this new Africa puzzling. It upsets almost all their established ideas about it. But who formed those ideas for us? Early explorers, imperialists, colonists – and, today, aid workers. Foreign aid is no longer about charity but a huge global business worth an annual $134.8 billion, of which Africa alone accounts for $57.1 billion a year. And aid’s business is crisis. At their conferences and workshops in Geneva and New York, aid workers note the new hope in Africa, measure it against their press releases about African need and conclude that reports about Africa’s rise are unhelpful.

Two years ago, at a high-level forum of aid and development professionals convened by the UN general-secretary’s office outside London, I was asked, as a writer interested in development who had covered Africa for a decade, to draft a mission statement capturing the new hope and optimism in the continent and what aid’s role might be in that context. “Over the next decade and a half, close to two billion people will be lifted out poverty,” I began. “Never before in human history will the lives of so many be so improved in so short a time.”

The aid groups rejected that out of hand. What eventually emerged was a text that stressed poor world problems and the crucial role foreigners could play in fixing them. “We come together because 2015 is a generational opportunity for transformational change,” read the final text. “Our aim is to inspire actions that empower the marginalised and collectively tackle the root causes of inequality, injustice, poverty and climate change.”

So it is that even as Africa’s economies have started to make substantial gains, aid agencies have used their vast resources to pay for thousands of campaigns plastered across billboards and newspaper pages around the world telling us the place has never been worse. Undoubtedly, tough challenges lie ahead – Eritrea, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe and, increasingly, South Africa are mired in conflict and bad governance, and the fall in commodity prices will test those with even the most resilient economies including oil-rich Nigeria.

There’s no denying that Africa today is home to a unique inequality. With population increases, the number of Africans living on less that $1 a day has remained largely static at about 400 million. The number of African dollar millionaires, however, has doubled to 160,000 since the turn of the millennium. Easing the continent’s future prosperity, three quarters of Africa’s growth is now accounted for by sectors other than commodities, such as services, manufacturing and technology.

Aid campaigns help to drown out this new complexity. Even as poverty has decreased in Africa, foreign aid has quadrupled in the past 15 years. Africa’s rising economic clout may be the more current story. But Africa in crisis has remained the louder one.

A changing Africa, then, forces the outside world to overturn some of these misperceptions. The economic transformation raises the possibility of an end to absolute poverty. It also has profound political and spiritual implications. At heart, this is about freedom. Money gives ordinary Africans the means to push back at anyone pushing them around – be that their own dictators, the new generation of African religious extremists or well-meaning foreigners urging them to celebrate their women, children, wildlife or sexual diversity.

Half a century after Africans won their formal liberation, money is now giving them the substance of it – and that will change humanity. Since Africa’s new narrative will no longer be about weakness but resourcefulness, it should also kill off the notion that development is something rich people in rich countries do to poor people in poor countries through aid. Entrepreneurs are key to development, not food parcels.

This is a story epic enough to change all our minds about Africa, and perhaps about African economic migrants, too. Not least because just Africans are moving to the rich world in such numbers, the rich world is also moving to Africa in unprecedented fashion. In 2014, a year when global foreign investment rose just 1 per cent, foreign investment into Africa grew 65 per cent to $87 billion. Unlike the past, more than half of that money was intended not merely to fund the extraction and export of resources but to develop businesses serving domestic African markets. Where did Stelios Haji-Ioannou go to set up a new low-cost airline after leaving EasyJet? Africa. Where did Bob Diamond go to invest in banking after leaving Barclays? Africa. Also following the money are a million Chinese. Can there be a clearer sign of Africa’s changing prospects than a mass emigration to it from what, for 30 years, has been the world’s hottest economy?

In the same way, perhaps, Europe’s migration crisis might be some help in changing the outside world’s view of Africa. Illegal migration, as already noted, is an expensive business beyond the means of most poor Africans. That is to say: they don’t come because they’re poor. Increasingly they’re coming because they’re not. And look how many there are.

Alex Perry was a foreign correspondent based in Africa for 10 years whose work appeared in Newsweek and Time magazine. His book The Rift: A New Africa Breaks Free is published this month.