Talking to Lynsey Addario within the pristine surroundings of her London publisher feels, well, a little weird, to be honest.

The smooth, ordered lines of our meeting room seem barely able to contain Addario’s accounts of her day-job as one of the world’s most respected war photographers. Her many accolades include a Pulitzer Prize in 2009 and a prestigious MacArthur Genius grant worth US$500,000 (Dh1.84m) in 2010.

During 15 years covering conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, her more nerve-shredding stories include kidnaps, car crashes, death threats, sexual abuse and, more recently, something like post-traumatic stress disorder while grieving for comrades killed in the line of journalistic duty.

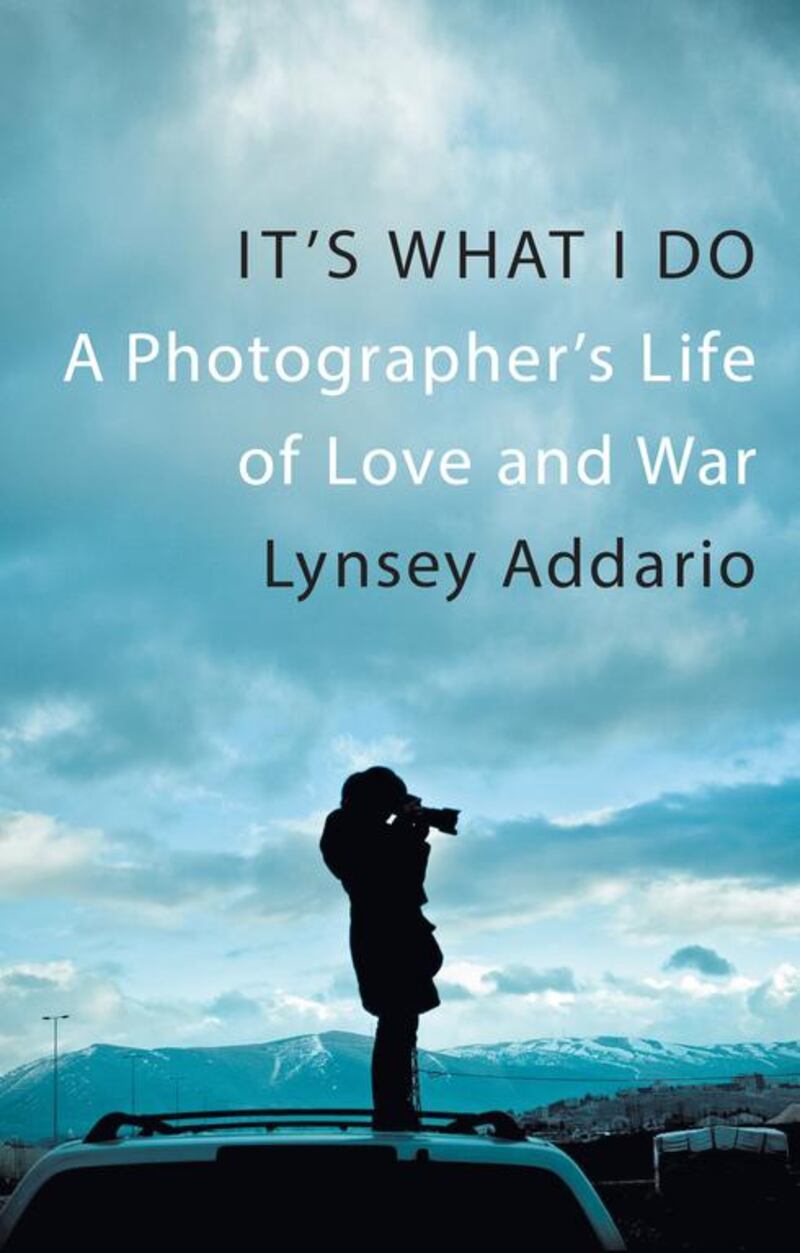

Addario in person only enhances the disjunction between her professional and off-duty selves. Petite and rather glamorous in a little black dress and elegant jewellery, she cuts a strikingly different figure from the woman glimpsed in the pages of her memoir, It's What I Do. There, it seems, she is clad stubbornly in jeans, sneakers and T-shirt, her hair tied back, a camera bag slung around her waist, a lens pointed at something interesting: an injured child, an anti-tank missile, marines under fire, a bereft Iraqi father.

What proves particularly disarming about our conversation, however, is the sheer calmness with which Addario recounts the intense bursts of violence and emotion that accompany life in a war zone. Take the event that made her briefly world famous in March 2011. Addario was kidnapped and held captive in Libya, alongside three other journalists from The New York Times, by a group of Qaddafi's soldiers. The ensuing torment is described with the sort of matter-of-fact tone I imagine she reserves for the dentist. "Yes, I am being hit in the face. Yes, I am tied up. And yes, I am being threatened with death – I have these guys caressing my face while they are telling me they are about to kill me. But I am in such a deep state of 'needing to get through this day alive' that there is no time to process the fear."

Even the horrifying sexual nature of her treatment is examined with cool detachment. “Look, I felt like I got off easy because I wasn’t being smashed in the back of the head by a gun butt. Yes, I was being groped. Every single soldier in Libya was touching my breasts and my butt. I was terrified I would be raped. But I wasn’t being hit on the back of the head with a gun. The men felt the opposite, like this poor woman is being sexually assaulted. No one has the right to say which kind of trauma is worse. For me just listening to them getting beaten up day after day was the most miserable experience. I felt like I couldn’t do anything.”

Their release after almost a week did not heal the psychological wounds. The murder of Addario’s driver in Libya weighed heavily. “We were grappling with all sorts of conflicting emotions. Relief that we survived, but real sadness and despair that we had basically killed our driver with our selfish need to continue covering this story when we should have left.” Did you really feel responsible, I ask? “One hundred per cent. All of us felt that. We talked about it openly because we needed to.”

Similar frankness can be found in It's What I Do, which was written as a kind of long-neglected therapy. The immediate spur was the death in 2011 of two close friends and colleagues, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros. Addario had been preparing a collection of her photographs when she learnt the news. "That set me up for a whole load of trauma and residual trauma that oddly I hadn't experienced right after Libya. I collected my photographs and had a breakdown," she says, laughing. "Then I said, I don't want to look at these pictures for the next year. I would rather write a book."

The memoir's wordy subtitle – A Photographer's Life of Love and War – suggests that it does more than simply recount Addario's riskiest shoots. There are frank dissections of the broader emotional toll exacted by her vocation: failed relationships, missed family gatherings and the new professional caution demanded by motherhood.

Addario herself was born in Connecticut in 1973, one of four sisters. Hers was a happy childhood until her father, who ran a local hairdressing business with his wife, left the family for another man. Addario was 8. Her father might have caused her earliest emotional sorrow but he would also inspire her most enduring joy. He gave his daughter her first camera when she was 13. It arrived at a vulnerable moment. Addario and her mother had just left their once-happy family home: her three sisters had already moved out.

This conjunction of events established the consoling power of photography under times of severe stress. "The camera was a comforting companion," Addario writes in It's What I Do. When she tells me about the restorative process of writing the memoir, it is the language of developing film that she employs. "I felt there was so much in my head that I hadn't processed. For years I just photographed and photographed, went from country to country and war to war. I never processed anything I was seeing. I processed it in my own personal way, through my work. But I felt like I needed to download my brain."

I ask whether photography has provided a shield against pain. “Totally. The camera does remove me one step. Sometimes when I am photographing and I find myself being overcome with emotion, I take my camera away, and it is almost too much to bear. I have to physically put the camera back in front of me and focus on the picture until I finish the work.” It doesn’t always succeed, however. Addario remembers being too upset to photograph the grief of young girls learning their mother had died of breast cancer in Uganda. “I make no excuses for becoming emotional. I am human. I have watched so many people die. I never get jaded to that, and I don’t ever want to get jaded to that.”

That first camera began a complex but enduring love affair between woman and machine. This was made almost literal when 25 year-old Addario asked her father for funds to kick-start her freelance career. Her sisters, she argued, had been given $15,000 (Dh55,000) for their weddings. Why couldn’t she have the same amount for much-needed equipment? “I think I made it very clear that nothing else compared to that passion for my work. I tried for many years to date and fall in love and be present in relationships when frankly I was anything but present.”

After marriage to her camera, Addario settled down to learn the nuts and bolts of photojournalism. She travelled to Cuba, snapped Madonna in Argentina and Monica Lewinsky in New York. But the life of the domestic paparazzo was never going to satisfy. In 2000, Addario relocated to New Delhi. “Very quickly I realised that many of the journalists covering India were covering Afghanistan.” Ed Lane, the Dow Jones bureau chief, encouraged her to cross the border. “He said in a matter-of-fact way; ‘You’re a woman, you care about women’s issues. You should go to Afghanistan because there aren’t that many women working there right now.’”

Was she anxious? “There was nothing scary about what he was saying. The Taliban was giving visas. It wasn’t like you were sneaking in. The Taliban wanted to prove to the outside world that they had given stability to Afghanistan. They didn’t want anything to happen to journalists on their watch. As scary as the Taliban was, journalists were able to work there.”

Nevertheless, Afghanistan in 2000 did pose unique challenges. “I was still learning how to photograph, especially in sensitive situations. Photography of any living thing was illegal under the Taliban. I had to sneak around.” Ironically, this same prohibition also made her work easier. “Because there were no newspapers coming into Afghanistan, people were very open to being photographed. They knew those images would never make it back.”

Addario also realised that her gender, sexuality and career confused many people in the Islamic world. “The only questions people asked were: ‘Are you married?’ and ‘Do you have children?’ I couldn’t understand why they didn’t care what I did for a living. In the West, we are all about how successful you are and how much money you make. Now I get it after 15 years working in the Muslim world.”

There were also immediate advantages. Addario’s gender allowed her to boldly go to places where men were not allowed. “I had access to all these women behind closed doors. The Taliban wouldn’t go into private houses. They wouldn’t go into the women’s hospital.”

These early stories about secret girls’ schools, professional women robbed of their professions and women’s health care were driven by Addario’s instincts and interests. Everything changed on September 11, 2001, a day that effectively created a new generation of war correspondents, including Addario herself.

Based in Istanbul, she would spend much of the next 15 years in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iraq. Photographing Kurdish peshmerga outside Khurmal, Iraq, she witnessed her first car bomb, which was detonated at a checkpoint packed with TV crews. Addario had been standing beside one of the victims, an Australian cameraman named Paul Moran. It was the first time Addario fully realised that journalists might also get killed in war. Not only would such attacks become routine in her work as a war correspondent, but they would also strike close to her adopted Turkish home.

In 2004, she was kidnapped for the first time on the “smuggler’s route” outside Baghdad. Watching her colleague and short-lived boyfriend Matthew taken off to likely execution, Addario interposed, believed her gender might make a difference. “You make those calculations,” she says. “In those situations, the last thing you want to be is this loud, screaming woman because it will probably backfire. In my experience a woman’s presence does give people pause in that part of the world.”

Addario credits her presence while being held in Libya a decade later with similar pacifying effects. “Anthony Shadid [a fellow hostage] wrote me an email saying: ‘Had you not been with us, they would have executed us in a second.’ I don’t say that to say I saved everyone’s life. I say it to note that in these cultures a woman’s presence in a man’s world makes people stop for a moment.”

Similarly forthright opinions are voiced about the role of the war photographer. “It’s about being present for history. It’s about bearing witness. It’s about having a front-row seat to every single thing that’s unfolding throughout my life.” Such first-hand reports, she insists, can shape public opinion and even influence global policy. “It’s about being able to provide those images to people in positions of power who wouldn’t otherwise be able to make decisions about foreign policy. It’s because of journalists that those guys understand what’s happening on the ground. Sure, they have advisers, but those guys are in Washington. They never leave [Baghdad’s] green zone.”

Recording the objective truth of conflict can be problematic, as Addario learnt during one especially hair-raising shoot in Afghanistan's Korengal Valley, known as "the cradle of jihad". Addario photographed a young boy, Khalid, whom she believed had been wounded by American bombs. She was backed up by Elizabeth Rubin, her New York Times colleague, and captain Dan Kearney, leader of the platoon with whom the journalists had been embedded. Doubting the exact cause of injury, The New York Times refused to print the image. Addario, who includes the image in the memoir, was heartbroken and furious.

“It seemed pretty clear to me what happened. There is always the chance that he wasn’t actually injured in that bomb, but our responsibility as journalists is to put it out there and let people debate it. That’s part of war and ambiguity in war. We risked our lives for two months,” she adds. “I am not trying to sensationalise anything. The story is sensational enough. It is about capturing reality in a way that will arrest people and make them ask questions.”

The Korengal Valley episode raised other questions, not least about the lengths Addario was prepared to go to for the perfect picture. Aware that a B-1 bomber was killing civilians, Addario writes that she could “endure anything but the prospect of missing the photo”. Elsewhere, she declares herself ready to die for an important story. “I don’t think I was aware of the risks early on. I threw myself into covering Iraq before I understood what that meant. When I started seeing people get killed, I started to think: Do I actually want to do this? Once I realised I did, I accepted dying as a possible consequence of my work.”

Circumstance has forced her to reassess this certainty. First, she became a mother, to Lukas, in 2011. “I want to stay alive. I have to stay alive. It’s not like I didn’t want to stay alive before. But before I had a child it was different.” While Lukas has not forced a change of career, Addario has modified her modus operandi. “How do I keep doing this work and come home at the end of an assignment? I am trying to still cover war zones but I do it in ways that I feel I can stay alive.”

The other seismic shift is the perception of journalists in the Middle East. Respect has grimly given way to barbaric murder as evidenced by the executions of James Foley and Steven Sotloff. “There are bounties on all of our heads. The sanctity about journalists as neutral observers doesn’t exist anymore. We have lost a lot of friends in the last 10 years. I think many of my colleagues are re-evaluating how to keep doing this work.”

I ask whether a small part of her would love to get into Raqqa and photograph life under ISIL. “Ten years ago there probably was. But I look at ISIS … Syria has basically swallowed up so many journalists. Even the most seasoned journalists won’t go there. They just think it’s a death sentence. I have to be realistic.”

This new pragmatism has meant working on Syria’s borders photographing refugees in Iraq, Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. Saudi Arabia has been another regular work location. One final destination is the silver screen: rumours that Addario’s story will be adapted by A-list chums Reese Witherspoon and George Clooney are greeted with tight-lipped silence.

Now based in London, she spends roughly two weeks a month at home – it used to be five days. She talks warmly about the time she spends in Iraq and Afghanistan, but is candid about what she finds difficult.

“I watched this woman Farkhunda get killed on the street [in Kabul] a few days ago. Are they still stoning, beating and burning women to death and no one steps in? They accused her of burning the Quran, which she had not. While so many of these countries are home to me, they are also foreign. There are things I will never be able to understand.”

This doesn’t mean she won’t continue to document the region, to process its beauty and horror, its joy and suffering. It is, after all, what Lynsey Addario does. “Having a camera is like having a passport to walk in and out of everyone else’s life. You can watch a woman give birth who you have never met in your life. You can only do that with a camera or a notebook. When you are a journalist and you have a reason for being there, then you are able to get access to almost anything. And nothing is impossible.”

James Kidd is a freelance reviewer based in London.