Martin Scorsese turns 70 later this year, but nothing about the film-maker who brought us Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Goodfellas suggests a grand old man ready to enjoy some well-earned relaxation in his twilight years. When he enters a room, the molecules in it seem to shift around: he's like a coiled spring, a bundle of nervous, caffeinated energy.

Along with Steven Spielberg and Woody Allen, he's one of the few directors whose name and face are recognisable the world over. And he didn't get to that point by avoiding hard work. Marty, as everyone calls him, always seems to have a new film just out, a couple more in the pipeline and a further handful being considered. He shrugs when I point this out: "I have a lot of interests," he says, "and it suits me to keep a lot of things going at once. That stimulates me."

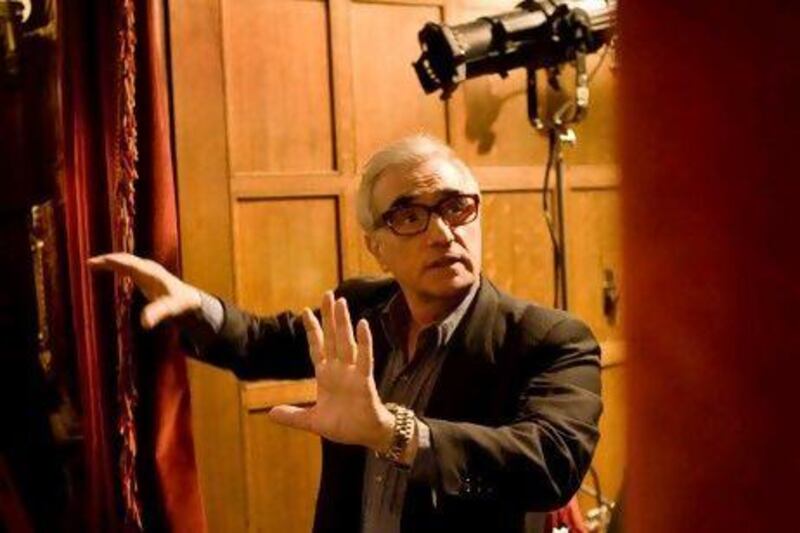

Scorsese greets me looking dapper in a dark suit, with a wide grin. His hair is white these days, but his eyes twinkle below bushy, jet-black eyebrows and behind his trademark horn-rimmed glasses. He's just 5ft 3in, but seems to exude enough energy to power a small city; he talks a mile a minute, gesticulating wildly as he does so. I saw this at first hand recently when I enjoyed maximum exposure to him over two days.

First, I chaired a Q&A session in London for members of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (Bafta) after a screening of his latest film, Hugo, a 3-D family extravaganza that is also a love letter to the magic of cinema. Scorsese joined me on stage with its producer, Graham King, and one of its lead actors, Ben Kingsley. All three were there to talk about Hugo, but Scorsese's charisma is such that the seen-it-all film professionals in the audience had eyes (and ears) only for him. I noticed them leaning forward in unison whenever he spoke.

The next day, he and I talked alone for an hour in a London hotel suite - about Hugo, mortality, fame, parenthood, films and Britain, a country he loves. Of course, he did most of the talking, at his usual rat-a-tat pace. Any question was a mere starting point for an intoxicating verbal thrill ride on Scorsese's high-speed train of thought. Afterwards, I felt exhilarated - and exhausted. Who could keep up with him?

"I really love it in Britain," he says. This wasn't just routine courtesy from a polite American visitor; he means it. He shot most of Hugo in the UK, relished working with the skilled local crews, and got a kick from the affectionate way they called him "guv". He traces his affection for the country to the films he loved as a child: "They were American, British, Italian neo-realist," he says. "They shaped and formed the films I made myself." He reels off classic British film titles - The Red Shoes, A Matter of Life and Death, Brief Encounter - and recalls the New York cinema in which he saw them, how old he was at the time, and who took him.

He and his long-time editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, widow of the great British film-maker Michael Powell (he co-directed The Red Shoes and was a huge influence on Scorsese) long have been working on completing a documentary of his favourite British films from the 1940s to the 1960s. "It's the next thing we're looking at," says Scorsese at first. "Well, maybe in the spring." A pause. "Make that May. Yeah, we should have a rough cut in May."

His schedule and dizzying range of commitments make it hard to pin himself down to a definite schedule. Still, his love for Britain and its films is genuine. As it happens, Britain loves him back. Bafta has now announced that Scorsese will be presented with one of its coveted fellowships - putting him in the esteemed company of Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Elizabeth Taylor and Laurence Olivier, among others. He'll receive it at the Bafta awards ceremony tomorrow.

Remarkably, Scorsese seems to have upped his prodigious work rate in the past decade. Friends claim he has a new spring in his step since his 1999 marriage to the book editor Helen Morris; they have a daughter, Francesca, who is now 12. It's his fifth marriage, and easily the most enduring - all the others (including his third, to Isabella Rossellini) ended in divorce.

Francesca is one of the reasons he made Hugo, his first film targeted at a family audience: "I wanted something she and her friends could see and enjoy." He looks sheepish for a moment: "Some of the films I make, the characters may not be the nicest people to be around." Given that his best-known characters have included vicious mobsters, small-time crooks and a deranged loner vigilante, he has a point. Though Scorsese has two daughters from previous marriages - Catherine, now 46, and Domenica, 35 - he finally seems to be at a more contented stage of his life, and can truly appreciate fatherhood. Not that he doesn't deliver stern lectures to Francesca and her pals about watching films at his home: "I tell them they have to be seen on a big screen," he says, chuckling. "And I make them put their iPhones away. They tell me they can watch movies on their iPhones. Hah! You think they're going to watch Lawrence of Arabia for more than 10 minutes on an iPhone?" He shakes his head in mock horror.

Watching Hugo now, he says, it's clear to him that his present role as a doting parent has seeped into the film. Hugo is about a 12-year-old orphan boy (Asa Butterfield) who lives secretly within the walls of a Paris railway terminal; he and a young girl (Chloë Moretz) team up to uncover a mysterious secret about Hugo's late father.

"For me, the great thing about 3-D in the film was seeing the close-ups and medium shots of the kids," Scorsese reflects. "Being around children a lot as I am, you're hugging, embracing them and kissing them a lot. And I wanted the audience to have that same feeling of warmth and closeness to them. Well, 3-D does that."

So is Scorsese finally becoming softer and cosier in his later years? Perhaps so, but he really had no choice. Enough friends, colleagues and ex-spouses have testified to his extraordinary intensity, his bouts of anger, his need to live life on the edge, as if time were running out.

Maybe it was. He suffered from chronic asthma and often had to resort to oxygen masks and occasionally oxygen tents to alleviate the condition. And then there was his relationship to cinema, which has always been fanatical: as a film director, Scorsese used to feel he was on a divine mission.

This is no idle exaggeration; some years ago Scorsese, who grew up in New York's boisterous, rough-hewn Little Italy district, told me that as a young man he was torn between his vocation to be a priest and his burning desire to direct films. The church and cinema, he said, were "the sacred and profane. They're both places where people gather and they both meet a spiritual need to share an experience and a common memory." These days he calls himself "a lapsed Catholic, but still a Catholic".

No wonder, then, that he approached his chosen career with such religious fervour. In the past 40 years he has made more than 20 full-length feature films, and if they share anything, it's a blistering intensity: Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Goodfellas, of course, but also other classics including Mean Streets, Casino, Gangs of New York and The Aviator.

In his earlier career, he made stars of Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel and Joe Pesci; more recently he has provided a steady supply of lead roles for Leonardo DiCaprio. Yet his films, many populated by thuggish characters, were too edgy and scurrilous for Hollywood tastes. It was not until 2007, with The Departed, that he won an Oscar after what looked like a series of deliberate snubs.

With Hugo, he has his seventh nomination, and the film leads this year's Oscar race with 11 nominations, including best picture.

But those films represent only part of Scorsese's body of work. No one has done more to capture the vitality of popular music for viewing audiences. He worked as an editor on the massive concert film Woodstock, and ever since has famously edited his films to music - with electrifying results. (He has used the Rolling Stones' riveting Gimme Shelter three times on a soundtrack to his films.) His music documentaries - including The Last Waltz (about the final concert by The Band), The Blues, No Direction Home (about Bob Dylan), Shine a Light (the Rolling Stones) and last year's George Harrison: Living in the Material World are majestic tributes to extraordinary talents.

It doesn't stop there. Scorsese is the global figurehead of a movement to restore and preserve old films. The Film Foundation, which he founded 20 years ago and still chairs, has restored about 450 films to their former glory, ranging from Wings, the first Oscar winner in 1927, to Rashomon, the 1950 masterpiece that opened up Japanese cinema to the world, and The Red Shoes, Powell and Emeric Pressburger's ballet melodrama in ravishing Technicolor, which burned itself onto his brain when he was a child.

It's the kind of schedule that might make lesser men want to lie down in a darkened room just contemplating it. And even Scorsese concedes he has started wondering how many more films he has left in him.

"I got to that stage during the shooting of Shutter Island [2010]," he admits. "That was a hard film to make. There was a lot of physical exertion involved. It was a complicated film that seemed simple, but once we got into it, it wasn't simple at all.

"Film-making isn't easy. Getting films financed isn't easy. The George Harrison film took four or five years. I began to feel, how many more can I do?"

So, how many? "Two," he says quickly. "I want to adapt the Japanese novel Silence by Shusaku Endo. And for over a decade now, Mick Jagger and I have been talking about something we think could go to HBO. It'd be a TV series about the music business in the last 40 years. We really want to do that." A pause. "Between those two, that's it, I guess."

A longer pause. Then he says: "Well, Bobby De Niro and I have something in mind, too. And Leo DiCaprio and I have an idea we've talked about."

More than two, then. You sense he can't help himself. And now there's news that he's planning a biopic on the life of another celebrated Italian-American, Frank Sinatra. Will Martin Scorsese be winding down soon? You wouldn't bet on it.

The Scorsese file

BORN November 17, 1942, Queens, New York

SCHOOLING Cardinal Hayes High School, the Bronx, New York; New York University College of Arts and Science (bachelor's in English, 1964); NYU Tisch School of the Arts (master's in fine arts, 1966)

FAMILY Three daughters: Catherine, 46, with first wife Laraine Marie Brennan; Domenica, 35, with second wife Julia Cameron; Francesca, 12, with fifth and current wife Helen Morris

TURNED DOWN The role of Charles Manson in the US TV film Helter Skelter

DIDN'T HAPPEN Film with Marlon Brando about the American Indian massacre at Wounded Knee

QUIRKY FACT ONE Taught both Oliver Stone and Spike Lee at NYU

QUIRKY FACT TWO The first film he saw at the cinema was Duel in the Sun (1946) at the age of 4

QUIRKY FACT THREE Served as an altar boy at Old St. Patrick's Cathedral In New York, which was used in his early films Who's That Knocking at My Door (1967) and Mean Streets (1973)

QUIRKY FACT FOUR Is the subject of the song Martin Scorsese by the alternative band King Missile

The quotable Scorsese

"Because of the movies I make, people get nervous, because they think of me as difficult and angry. I am difficult and angry, but they don't expect a sense of humour. And the only thing that gets me through is a sense of humour."

On Robert De Niro: "I still know of nobody who can surprise me on the screen the way he does. No actor comes to mind who can provide such power and excitement."

"As I grow older, I find that I just need to be quiet and think."

"If I continue to make films about New York, they will probably be set in the past. The 'new' New York I don't know much about... I find the new colours of the city, the new Times Square, kind of shocking."

"My whole life has been movies and religion. That's it. Nothing else."

On Stanley Kubrick: "One of his films... is equivalent to 10 of somebody else's. Watching a Kubrick film is like gazing up at a mountain top. You wonder: 'How could anyone have climbed that high?'"

"It's hilarious, the problems that arise when you're on the set. It's really funny because you make a complete fool of yourself. I think I know how to use dissolves and the grammar of cinema. But there's only one place for the camera. That's the right place. Where is the right place? I don't know. You get there somehow."

"Movies touch our hearts and awaken our vision, and change the way we see things."

On working with Liza Minnelli on New York, New York (1977): "After 15 minutes I realised that not only could she sing, she could be one hell of an actress. She's so malleable and inventive. And fun."

"I'm not a Hollywood director. I'm an in-spite-of Hollywood director."

"There are two kinds of power you have to fight. The first is the money, and that's just our system. The other is the people close around you, knowing when to accept their criticism, knowing when to say no."

Source: Internet Movie Database