Discussing the 1967-1970 Civil War that inadvertently shaped Nigeria’s unique strain of 70s rock music, Uchenna Ikonne reminds us that combat was largely confined to the country’s eastern region. He also notes that it was subject to “a firewall of government propaganda that denied the country was at war at all”.

Those in the western and northern regions, the author writes, were “virtually unaware that while they [danced] the Mashed Potato at soul music extravaganzas, federal Nigerian troops were massacring millions of their countrymen or enforcing sanctions that led to rampant starvation…”

Up to three million people died in the war which ended Biafra’s brief secession from Nigeria. But even during the capture of Port Harcourt, the crucial city that Nigerian Federal forces regained in May 1968, local bands played on.

Nigerian rock’s glory days

■ Podcast — John Dennehy talks to Uchenna Ikonne about Nigeria, music as a tool of war and Fela Kuti

One of Ikonne’s many interviewees is Renny Pearl of The Figures, a group whose under-the-radar gig circuit took in makeshift hospitals and refugee camps. When the bombs and gunfire eventually stopped, Pearl slung his acoustic guitar over his shoulder and ventured out to see if the war had indeed ended.

He was soon ambushed by the 13th Brigade of the 3rd Marine Commandos, who took him for a fleeing combatant. “I showed them my guitar and told them, ‘I’m not a soldier, I’m a musician’,” Pearl relates.

After he and a miscellany of other remaining musicians staged an impromptu gig for the soldiers, the Brigade commander dubbed Pearl’s makeshift act The Actions, put them on salary, and made them the 13th Brigade’s official band.

They later became the first East Nigerian rock group to record at EMI Africa’s Lagos studios, but when the army appropriated their profits and wanted to conscript the band as soldiers, The Actions opted to dissolve the group and return their forces-owned instruments.

Though it largely concentrates on rock music made in the decade after the Nigerian Civil War, Wake Up You!, the first of two paired volumes by eloquent Nigerian musicologist Uchenna Ikonne, is full of such fascinating details.

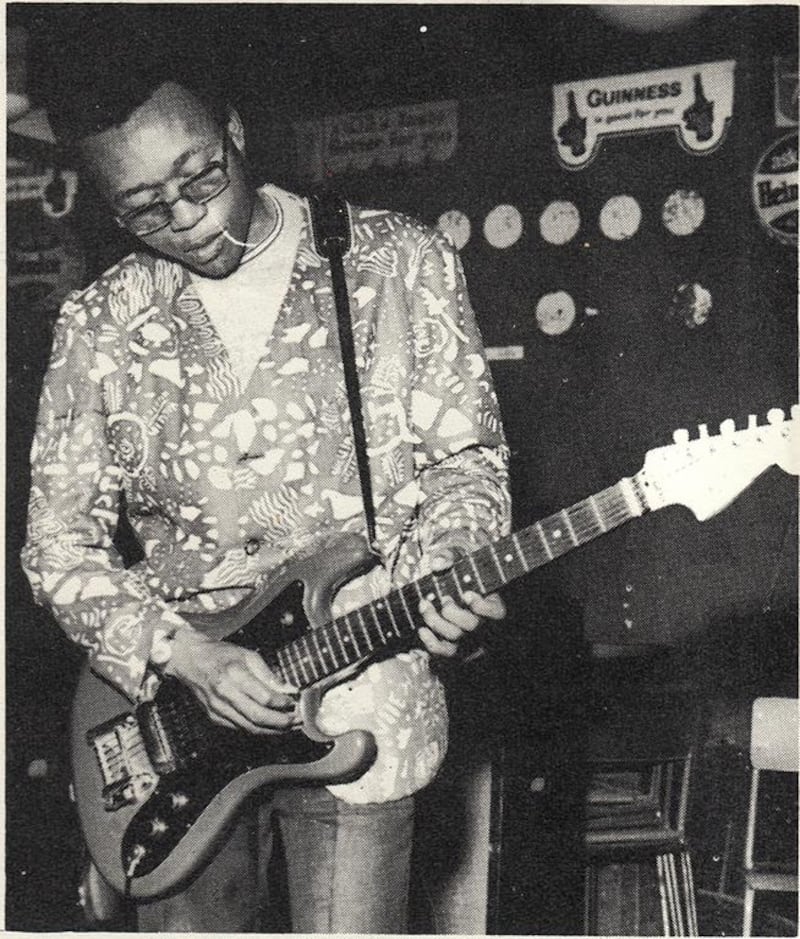

It also has scores of arresting photographs – guns and ammo occasionally loom as large as guitars and amps – and comes with a wonderful, 18-track CD compilation featuring many of the bands discussed.

The author is good on how celebrated Nigerian superstar Fela Kuti’s late 1960s rejection of “pure Highlife” music (his new “Afrobeat” sound also incorporated R&B and Latin jazz elements) helped to pave the way for the leaner, meaner sound of “Afro Rock”, a genre pioneered by bands such as The Hykkers, who were Biafran transplants to Lagos.

As the 70s got under way, there was an audible, psychedelic-sounding fury in Afro Rock songs such as Graceful Bird by the band Warhead Construction, and although some acts disbanded as their players resumed the educations the civil war had derailed, the many bands who pressed on – The Magnificent Zenians; Wrinkar Experience; The Hyrades, The Founders 15, etc. – had a new energy and purpose.

The Afro Rock band Ofo & the Black Company sound particularly intriguing. Ikonne describes them as “loud, freaky, theatrical and spiritual”, and “undoubtedly the strangest bunch of musicians to ever [grace] the Nigerian music scene”.

Fronted by charismatic lynchpin Larry Ifedioranma, and rocking an Afro-shamanic look, they took their name from the ofo, a sacred staff. This artefact signified authority and ancestral destiny for the Igbo, the indigenous, culturally-rich people of southern Nigeria.

It was when Love Rock – a soulful 1972 single by the Owerri, Imo state, formed band Strangers – became the fastest-selling Nigerian single of all time, Ikonne explains, that the record label wars that had long raged between the African outposts of EMI, Decca, Philips and Polydor went into overdrive.

Each of them sought the lion’s share of the rapidly expanding Afro Rock market, and each of them had their different strengths. EMI, for example, had signed the ever-influential Fela Kuti to its Parlophone (in Nigeria, later renamed HMV) imprint. It also had a true mover and shaker on the ground in Lagos in the shape of gifted producer and recording engineer, Odion Iruoje, who had been trained at London’s Abbey Road studios while The Beatles still recorded there.

It was Decca, though, the first label to build professional recording studios in West Africa, that seized the day, rebranding itself as Afrodisia. This new imprint aimed to embody “Black consciousness, uninhibited sexuality, and a laid-back bohemian ethos.”

Though it was savvy enough to sign Ofo & the Black Company, Ikonne argues that, operationally at least, Afrodisia ultimately succumbed to style over substance. Lacking any real commitment to artist development, the imprint “bled talent as artists fled to EMI”, he writes.

As the book progresses, we learn about other figures crucial to the efficacy and potency of Nigerian rock. Goddy Oku, the Hygrades member and able electronics engineer who built guitar amps "for cash-strapped musicians". Felix "Feladey" Odey, the virtuoso guitar-for-hire who played on scores of Nigerian rock records. Ofege, the psych-rock schoolboys from St Gregory's College, Lagos, whose debut LP Try And Love was the biggest-selling album of the era.

There is even a section on Ginger Folorunso Johnson, the percussionist, film score composer and Nigerian /Afro Rock pioneer who backed The Rolling Stones on Sympathy For The Devil in Hyde Park in 1969.

Oddly enough, it seems the ubiquitous Fela Kuti also played a part in the downfall of Nigerian rock, albeit indirectly.

Ikonne explains how, in the mid-to-late 70s, Fela’s bohemian, extremely alternative lifestyle made Nigeria’s conservative government feel genuinely threatened.

But when military head of state Olusegun Obasanjo imposed punishing taxes on the import of musical instruments / equipment in an attempt to hurt Fela, he merely succeeded in putting most Nigerian rock bands out of business.

“The grunge was gone, [to be] replaced by gloss”, notes Ikonne, but his fascinating, diligently-researched book makes a compelling case for the worth and restorative power of Nigerian rock. For those in the war-torn East of the country, he suggests, this short-lived, all-but-forgotten genre was a lifeline; the thing “that got them through hell”.

James McNair writes for Mojo magazine and The Independent.