Every now and then humankind puts on its thinking cap to achieve the miraculous. For the Nasa scientists of the 1970s behind the famed Voyager project, "reach for the stars" was more than a generic phrase of encouragement – it was their real-life mission as ambassadors of Earth.

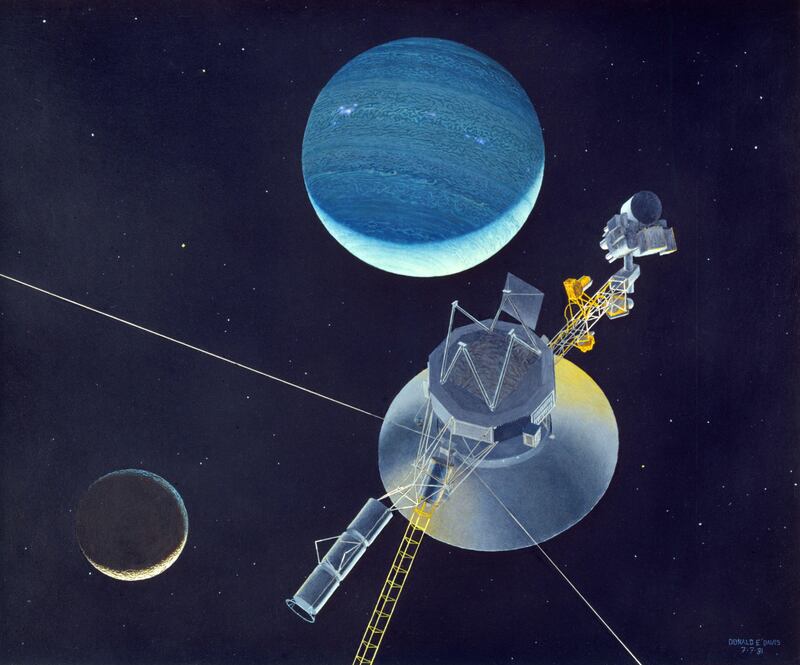

After the twin space probes, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, sped away from Cape Canaveral with their 1977 launch, we soon thrilled on a planetary scale to heretofore unseen images of swirling gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, ice giants Uranus and Neptune and their new and exotic moons, some with atmospheres and even bubbling ice volcanoes.

"We felt like we were there," says Voyager's chief scientist Ed Stone. "Nobody even thought about it. Voyager was part of us." Today, more than 13 billion miles away, the tiny Voyager 1 spaceship is leaving our solar system for the void of deep interstellar space – the first man-made object ever to do so. Voyager 2 is not far behind. Billions of years from now, when our Sun flames out and toasts Earth to a crisp, it may be the only proof in the cosmos that we ever existed.

The Farthest, a new feature-length science documentary that airs Sunday on OSN First HD Home of HBO, sparkles with awe and wonder as it celebrates the 40th anniversary of these magnificent machines, the men and women who built them and the vision that propelled them farther than anyone could ever have hoped.

Dublin-based director Emer Reynolds spins a truly riveting doc that already enjoys a perfect 100-per-cent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and rave reviews across the board.

She is a pro at infusing tension and real-life drama into his storytelling; she previously directed Here Was Cuba (2013), a landmark documentary commissioned by American broadcaster PBS to mark the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis – the closest that humankind has come to nuclear destruction.

“In the 4.5 billion years of Planet Earth, modern humans have been around for barely 200,000 years, have developed technology in the last few hundred and have just now reached interstellar space,” Reynolds says. “The story of Voyager thrills me to the core.

“With less computing power than a modern hearing aid, they have unlocked the stunning secrets of our solar system on a journey as revolutionary as the first circumnavigation of the globe and mankind’s first footprint on the Moon.”

The planets had to be lined up just the right way – a cosmic alignment that happens only once every 176 years – for Voyager to make the grand tour of our outer solar system. Although Congress in the United States dictated the journey end at Saturn, Nasa engineers slyly designed the spacecraft to last at least until Neptune – and beyond.

The fact their cosmic twins are still functioning, and beaming back messages to Earth 40 years later with data from their deep-space travels, has exceeded all expectations.

Slowly dying within the heart of each spacecraft, however, is a nuclear generator that will beat for perhaps another decade before the lights on Voyager finally go out.

But this intrepid little craft will race on for eternity – travelling about 17 kilometres in the time it takes to blink, far too fast for the eye to see, at more than 60,000kph – carrying its famous golden record bearing recordings and images of life on Earth, designed to be played by any intelligent life forms who encounter Voyager to tell them who we are (or were).

It didn’t take long to come up with the well-known surface sketch that serves as the key, or operating instructions, to aliens who may come across the golden record, says Jon Lomberg, a space artist and science journalist who helped to create it.

“It took me about three hours to draw it, and the estimated lifetime of it is a thousand million years,” he recently told BuzzyMag.com, a website for fans of speculative fiction.

“That’s how long it lasts. Because space is very, very empty. But occasionally, a tiny grain of dust will hit the surface of the record and make a little micro crater. So the question is, how long does it take before you completely wear away the surface? How long does it take the dust to wear through that box and destroy this drawing?

“And the conservative answer is a thousand million years. It may be two or three thousand million years. But that’s a long time. And how many artists get a chance to draw something that lasts a thousand million years? So I’m happy.”

"All of planetary exploration to me is a story about longing," says Carolyn Porco, the imaging scientist for Voyager and imaging team leader for the more recent Cassini mission to Saturn. "It's a longing to know ourselves. It's a longing to understand the significance of our own existence. It's a longing to communicate, to say to the universe: 'We're here, you know – know us. You know, where are you?'"

We can thank late astronomer Carl Sagan for one of the most famous images of Earth ever captured. After Voyager 1 completed its mission to Jupiter and Saturn, the eloquent scientist insisted it turn its camera inward.

Earth appeared as a pale blue dot on which, Sagan said at the time, “everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives … on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam”.

The Farthest has its premiere at 11pm on Sunday on OSN First HD Home of HBO

_________________

Read more:

[ Netflix cuts ties with Kevin Spacey after more misconduct allegations ]

[ Focus on the Philippines: Alisah Bonaobra returns to X Factor UK as wildcard ]

[ Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace is yet another must-see Netflix show ]

_________________