Talk show host Ricardo Karam was only a child when Lebanon's civil war broke out in 1975.

Yet he has built a career on evoking nostalgia for a bygone era of glitz and glamour that preceded the conflict.

The soft-spoken TV presenter last year hosted an online interview series called Tonight's Chat exclusively on The National, during which he spoke to high-profile personalities such as Prince Turki bin Faisal of Saudi Arabia and Zaki Nusseibeh, cultural adviser to the UAE President.

Karam rose to fame in 1990s Beirut. It was a period of reconstruction, economic progress and renewed hope in the city, with which his name has become indelibly linked.

His first show, Maraya (Mirrors), became an instant hit in 1996 for hosting stars who embodied Lebanon's pre-war halcyon years, transporting viewers to a time when Brigitte Bardot dined in the coastal city of Jbeil and Miles Davis and Ella Fitzgerald played against the backdrop Baalbek's ancient ruins.

Lebanon’s civil war ended in 1990.

The decade that followed saw the rise of reconstruction projects spearheaded by former prime minister Rafik Hariri, who was assassinated in 2005.

As the nation regained a semblance of stability, thousands of people who had been displaced by fighting returned home and Beirut re-emerged as a regional centre for culture and business.

"I belong to an era that is not easily forgettable," he tells The National from his office overlooking the port of Beirut, which was devastated in the deadly blast of August 2020.

“There was a thirst from people to hear the stories of those who witnessed the pre-war era,” he says.

“People wanted to hear the story of a beautiful Lebanon… They wanted to remember beauty.”

For many Lebanese, Karam's name is reminiscent of better days. Yet as economic collapse, political deadlock and the aftermath of the Beirut blast have plunged the country once more into despair, he remains optimistic that Lebanon will recover, having had a front-row seat to the country's cycles of rise and fall in the past decades.

“Every 10 or 20 years, we have catastrophes, internal wars, stupid wars,” he says. “We pay a high price, but we overcome it.”

The making of a household name

Karam studied chemical engineering in Beirut but his passion for music and entertainment drove him to a career in television. His gentle interviews with stars and statesmen of the past contrasted sharply with the heated debate shows popular on Lebanese TV, gaining him a loyal following in his early days.

"It was the era of faxes," he says, recalling the messages he would send out to celebrities every week during the '90s.

“I would only get refusals, but a refusal is not a no. I would send them messages on Christmas, Easter, Nowruz…”

Persistence landed Karam his first interview with an international figure, when he hosted Saudi philanthropist Prince Talal bin Abdul Aziz in 1998.

“It was my passport into that world,” Karam says.

Since then, Karam has hosted international A-list celebrities and people who have shaped the worlds of business and politicsm, a rare feat for an Arab presenter.

His guests included Bill Gates and the Dalai Lama, business tycoon Carlos Ghosn and Nicolas Hayek, the Swiss businessman of Lebanese descent who co-founded watchmaker Swatch.

He has also interviewed the main figures of pre-war Lebanon. One of them was the late singer Sabah, whose profile adorns a massive mural in Beirut.

"Sabah is the sun," Karam said of her during an interview in the late 1990s. He also hosted Georgina Rizk, who was crowned Miss Lebanon in 1970 and Miss Universe one year later, as well as the socialite and Baalbeck festival founder May Arida.

Those interviews are now "part of history", Karam says. As crises batter Lebanon once again, many of the country's citizens are now looking back at the period of reconstruction as another lost golden era.

Karam, however, sees it slightly differently.

“During the 1990s, we lived in a fictitious era of prosperity. We didn’t think there was something dangerous waiting for us later,” he says.

And so, the image of Lebanon that Karam has come to embody is long gone. After the assassination of Hariri, post-war optimism and prosperity gave way to economic stagnation. In the past 18 months, Lebanon has plunged into a deepening financial crisis that has been met with inaction from the political class.

Banks have prevented depositors from freely accessing their money. More than half of the population now lives below the poverty line and, last month, the country was labelled a "hunger hotspot" by the UN.

Karam says he now wants to focus more than ever on inspiring positive change in Lebanon and the wider region, and that drive has pushed him to remain in the country.

This has been the stated mission of his foundation Takreem for the past 11 years. Takreem gives awards to people from the region who, like many of Karam's former TV show guests, have risen to global prominence.

The foundation also bestows lifetime achievement awards on well-known, mostly Arab figures. This has included Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid, famed Egyptian actress Faten Hamama and former US president Jimmy Carter.

Takreem's hallmark annual ceremony welcomes Arab celebrities and socialites and takes place in a different Arab capital every year. Last year, it was held virtually in Beirut because of Covid-19 safety concerns.

While a certain dose of glamour has come to be expected from these ceremonies, the foundation's main goal is to bring regional success stories of Arab talent and entrepreneurship to the limelight, with a view to shatter stereotypes about the Middle East.

For instance, Iraqi cellist Karim Wasfi received a Takreem culture award last year. The musician is renowned for playing beautiful compositions amid the rubble at sites of attacks in Baghdad and in ISIS-ravaged Mosul, as an artistic plea to peace.

A message of resilience and persistence

Karam wants to bring a desperately needed sense of hope to his country, but the very idea of a "resilient" Lebanon has, for many, now become a tired cliché.

Many Lebanese have grown disillusioned after mass anti-government protests in late 2019 failed to bring about change. This disenchantment has only grown in light of a severe economic crisis and the Beirut port blast.

The explosion killed more than 200 people, injured 6,500 others and destroyed vast parts of the capital.

Yet Karam remains optimistic.

The tragic event reminded Karam of the “fiercest days” of the civil war.

“We all lost something at the time and we all rebuilt. This is the strength of the Lebanese,” he says. “The main difference today is that people have no money.”

In the aftermath of the blast, Karam interviewed President Michel Aoun and, later, the caretaker prime minister Hassan Diab, who both said they knew dangerous chemicals had been stored at the port for years.

"It was the most difficult interview I have ever done in my life because there was so much responsibility," he says of his talk with the president.

Many Lebanese and some in the international community accuse the political class, widely seen as corrupt, of failing to prevent the blast and the economic crisis. Days after the explosion, protesters took to downtown Beirut where they hung effigies, with ropes around their necks, and called for political leaders to be punished.

On the day of the interview Karam received “tonnes” of messages from people who lost relatives and friends in the disaster, asking him to be their voice.

Watch the full interview here:

On camera, he raised tough questions, asking Aoun why he had not met ordinary Lebanese after the explosion and questioning him on the allegations of corruption regarding his son-in-law Gebran Bassil, a former minister.

However, Karam sparked controversy by giving a white rose to Aoun at the end of the interview as a metaphor for the resilience of the Lebanese people.

Still, he says his conscience is clear.

“I asked all the questions that needed to be asked,” he says.

“If I had to do it again, I would do it in the same way.

“Everything I do today focuses on positive change, inspiring the youth and conveying a better image about who we are.”

Looking out at the port, Karam says that, despite the destruction, thousands of people have managed to rebuild their lives.

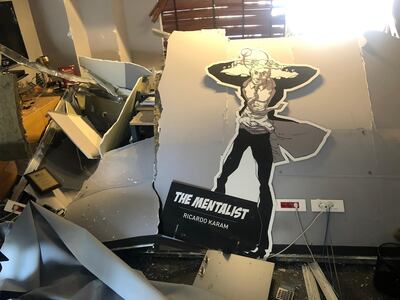

The elevators in his building have been out of service since the blast, which wrecked his office but did not harm any of his staff.

“We will fix them next week,” he says with a smile.