A YouTube clip of a cricket match shows a batsman without pads awaiting the ball's arrival behind the stumps – a position in which, ordinarily, the wicketkeeper would stand. As the bowler approaches, the batsman swaggers nonchalantly towards the wickets. He assumes an orthodox stance in front of them just in time to smack the ball high into a packed crowd when it arrives at lightning speed.

“Shaaat!” [shot] rasps an ecstatic commentator.

The clip, in which "Abubakar King of Lahore" can be seen awaiting delivery of the ball in any number of outlandish ways (behind, midway up the pitch and without bat in hand), has been viewed more than 409,000 times since January.

Welcome to the parallel sporting universe of Pakistani tape ball, where prize money and baseball-style chucking and bravado like Abubakar's are decidedly more common than what might be expected from a leisure activity derived from the gentleman's game.

What is tape ball?

Immensely popular, fiercely competitive, surreal and entertaining in equal measure, tape ball is played with a tennis ball wrapped in electrical tape, thus dispensing the need for wide open space and protective padding.

Invented in the densely populated, land-scarce metropolis of Karachi between the 1970s and early 1980s, tape ball's no frills, earthy, localised spirit of the streets is in stark contrast to the corporate razzmatazz sure to be on display at next week's ICC Cricket World Cup – a high stakes, carbon-intensive affair in which national squads from around the globe will be flown in to compete in front of crowds paying handsome sums for tickets and vast television audiences.

But many sports fans lack access to proper playing facilities; with barely enough space to swing a cat let alone a bat in cities such as Lahore, playing cricket relies on user-friendly adaptation. Tape ball flourishes spontaneously in gullies (streets) and small patches of concrete. Distinctly urban and designed for Asia's hot and humid conditions, it rarely commences before dusk and is often played after dark under lights, not least during Ramadan.

As a sensory experience, tape ball isn’t quite aligned with cricket’s purportedly decorous origins. The crude slap of inferior wood on rubber amid clouds of dust kicked up on concrete surfaces could hardly be further from the gentle knock of leather on willow, lush green outfields and ripples of polite applause you might expect in an English village.

There's not a cucumber sandwich in sight – just animated, wiry youngsters hollering and cursing as they scramble over petty wagers. At the very least, losers can expect to foot the bill for post-match parathas, lassi and spicy omelettes; more often, money changes hands among players or betting spectators.

The gambling culture

Despite being illegal, gambling is a significant aspect of tape ball. Its imprint is most evident in “single wicket” challenges, where individual players bat and bowl to one another without fielders to see who can clock up the most runs in a six-ball over. Announced at the last minute through word of mouth to avoid visits from the police, these compressed encounters, the cricketing equivalent of a penalty shoot out, make T20 look positively long-winded. Dozens can be seen on YouTube, but these clips convey little of the real life intensity of single wicket fixtures, which attract thousands of raucous spectators.

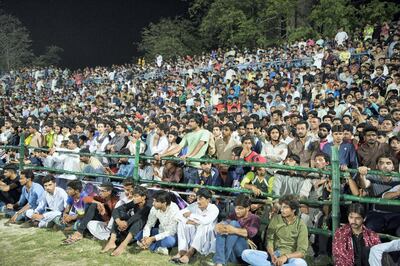

Organised, family-friendly tape ball tournaments sponsored by individuals and small businesses are played in grounds before thousands of spectators. Colourful kits, white tape balls and outrageous slogging are integral to this increasingly flashy genre, and many of tape ball's aesthetic quirks are directly inspired by official cricket's growing emphasis on fast-paced, big-hitting entertainment. Screened widely on Facebook and YouTube, the premium on big scores has led to increased pitch lengths and ball sizes to aid batsmen; drone cameras hover above the ground capturing the action on big screens, while commentators imitate Danny Morrison after every ball on booming loud speakers.

With prize money that can run into thousands of dollars, tournaments up and down the country are played by an increasingly professionalised class of specialists who earn around 15,000 Pakistani rupees (Dh389) for participating in any given match. Exceptional performers like Abubaker can receive much more. A reasonable living can thus be eked over the course of a season, with top players' annual salaries reaching between $8,000 and $10,000 – not bad in a country where the average per capita income was reported to be $1,629 per year in 2017.

Non-pecuniary rewards include the izzat (honour) and the reputational pride that come with being a star, adored and admired in the remotest of villages, where players are garlanded with flowers upon arrival, greeted with celebratory gunfire and paraded through towns and cities on camel and horseback towards grounds.

Crowds delighting in powerful batting performances have been known to stuff generous cash tips into players’ pockets as marks of respect and adulation, a customary gesture of appreciation traditionally accorded to dancers and musical performers.

A league of its own

However, not everyone in the cricketing fraternity is enamoured with tape ball. Prudish opposition to the gambling culture that surrounds it holds tape ball responsible for the match and spot-fixing scandals that have plagued cricket in general, and Pakistan in particular since the 1990s.

Coaches express concern about the chucking rife among younger exponents, as well as the unpreparedness of batsmen reared on tape ball for facing a real cricket ball that deviates off the pitch. Whatever the truth in these moral and technical issues, few deny tape ball has been central to Pakistan’s innovative contributions to modern fast bowling, not least the art of reverse swing, perfected by generations of pacers reared on tape ball; so too the finger spinner’s “doosra”, a delivery that requires bending the arm within legal limits.

Whatever the cricket establishment thinks, tape ball's live audiences, online viewers and supporters number hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions across Pakistan, its diaspora and well beyond, numbers that dwarf the modest crowds, which turn up to watch the national team play test matches in the Gulf, Pakistan's adopted international "home" since the terrorist attack on the touring Sri Lankan side in 2009. The on-and-off line stardom enjoyed by tape ball legends such as virtuoso batsman Shahbaz Kaliya, or Sir Shahbaz Kaliya, as he is respectfully referred to by admirers across the Punjab, is such that he launched his own line of cricket bats; at least one fan he knows of named a son after him.

A veteran and veritable legend of Lahore's Samanabad neighbourhood, who once hit 23 sixes in an innings of 25 balls, the now retired Kaliya cuts a charismatic figure, enjoying widespread love and respect from players and fans.

What does the future hold?

Kaliya is anxious for tape ball’s future in Lahore, where gentrification and a millennial real estate boom have caused the rapid disappearance of playing areas that allowed previous generations of cricketers to hone their batting and bowling skills.

This in turn has driven the city's flourishing tape ball cricket culture to construction sites, where youngsters inhale dust and play amid construction materials in one of the most polluted cities on earth.

Despite such difficulties, tape ball is alive and well in Pakistan, not least in semi-rural districts where there is space to play. A tournament I attended last month, the Depalpur Premier League, began with an opening ceremony of music, song, dance, fireworks and pitch invasions that lasted well into night. By the time the pitch was cleared and ready for play after 1am, the ground was packed beyond capacity – around 10,000 people. Modelled on the Pakistani Super League, the DPL is financed locally by individual landlords, businessmen, politicians and their male offspring, who purchase team "franchises", pay for players and distribute thousands of kits to garner support from around the city for their squad.

Before reaching the ground, visitors were greeted by posters advertising participating teams and their sponsors all over town. The atmosphere was festive, more like a carnival than a cricket match, with youngsters dancing on the pitch. I got talking to a young supporter of the "Superkings", and asked him if he was looking forward to next week's world cup. "What are you talking about", he laughed, "The world cup starts here."