Two years ago, Meitha Al Mazrooei and Rand Abdul Jabbar, two young architects, decided to form a partnership. The decision was born of frustration. Both had spent years studying their profession, Al Mazrooei at the American University of Sharjah (AUS) and Abdul Jabbar at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia and Columbia University in New York, but given their views on the way that architecture is understood and practised in the UAE – commercially, uncritically and as an adjunct to development – neither felt enthusiastic about entering the industry.

"Through our discussions about architecture and from working together on small projects, we realised that we wanted to work together on something more substantial," says Al Mazrooei, 27, the editor and co-founder of the Dubai-based architecture and design publication WTD Magazine.

“We were both architects who didn’t want to practise – and to be an architect here you really have to follow that route. But we are interested in alternative ways of discussing architecture that don’t necessarily have to manifest themselves in a physical building.”

The Centre for Architectural Discourse (CAD) is Al Mazrooie and Abdul Jabbar's initial response to what they see as the UAE's architectural predicament. The think tank has its launch next week with two talks held at Nadi Al Quoz, the pop-up arts hub at Warehouse 90 on Alserkal Avenue, Dubai.

“Architecture here is about development and real estate. It’s about building stuff and making money, but at the moment we don’t have the kind of research to be able to present an alternative case,” explains Abdul Jabbar, 26, who was born in Baghdad, grew up in Abu Dhabi and now lives in Dubai.

“The country also doesn’t have a particularly long history of architectural discourse, especially in the academic sense, and the history of architecture schools here aren’t that extensive, so there really isn’t a space where architecture can be explored through theory or criticism or writing.”

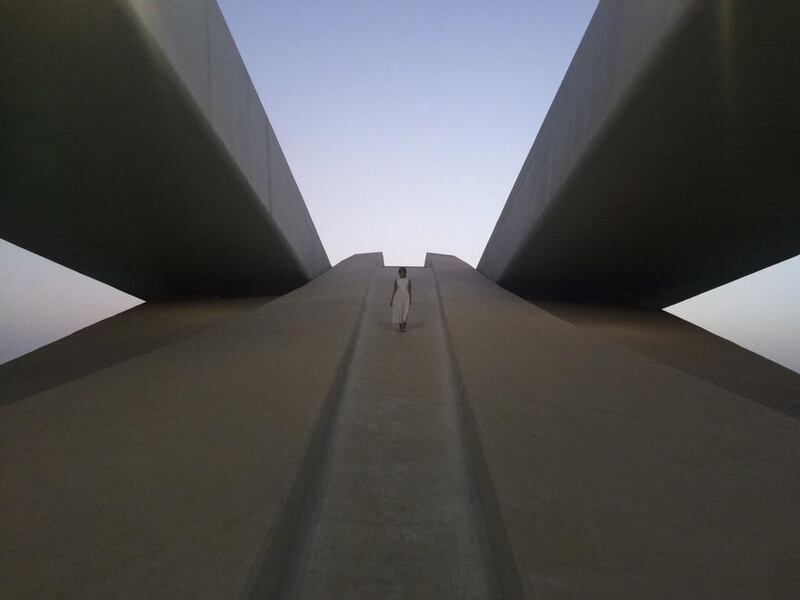

A clarion call for an alternative approach to the UAE's built environment, E11, the CAD's inaugural project and effective manifesto, is an idiosyncratic portrait of some of the structures, spaces and features that can be found along the UAE's longest road.

Stretching almost 560 kilometres from the Saudi border in the west to the Oman border in the east, the road that eventually became the E11 was first conceived in the mid-1960s as both a vital commercial artery and as a symbol of increasing political unity among the independent emirates that then constituted the Trucial States.

As the historian Matthew MacLean explained in a recent lecture at New York University Abu Dhabi, Spies, Subversion, and Skulduggery: The Thrilling Story of the UAE's First Paved Road, the process of building the first section of what was to become the E11, which now runs from Dubai to Ras Al Khaimah, was politically fraught from the very outset, as international powers – Britain, Egypt, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia – sought to control the development of infrastructure as a means of gaining political influence.

It is the role that the UAE’s roads and infrastructure have played in the formation of Emirati national identity however, that lies at the heart of MacLean’s ongoing research.

“One of the main results of the national road network, built from 1966 through the late 1970s, was that citizens could travel between emirates very quickly. So with the establishment of the federal government in Abu Dhabi, many people came from the northern UAE to work in the capital during the week,” MacLean explained in a recent interview with NYUAD’s Matthew Corcoran.

“As UAE nationals interacted with each other in government offices, university classrooms, and other spaces, people realised that they have some things in common. That’s how a national identity develops – not only as a direct result of a state project but also from the grass roots, through everyday interactions of ordinary people.”

Those interactions and responses to the highway sit at the heart of the book that forms the core of Al Mazrooei and Abdul Jabbar's E11 project. Comprised of an A-Z glossary in which each entry is accompanied by an image and a short written response from one of 26 commentators, the project also includes a diagrammatic map of the E11 and a short film by the Dubai-based photographer and filmmaker Ekta Saran.

“We were attracted to the idea of this singular line that stretches across the country with nodes along it that are so diverse and that tell such a multifaceted story,” Al Mazrooei explains.

“There’s a perception, even amongst lots of people who live in the UAE, that the country’s urban fabric consists of Abu Dhabi with its grid, all the development in Dubai and then Sharjah, but once you cut through the country in this way, you notice the variety,” she says.

"And E11 is an attempt to make people aware of what's in their backyard, and to try and understand it by bringing in other individuals so that our perception isn't the only narrative."

The list of individuals invited to take part in E11 reads like a who's who of the UAE's contemporary art and design scene. The commentator and art collector Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi is paired with "P" for Plurality, while the co-founder of Dubai's Third Line Gallery, Sunny Rahbar, the AUS faculty members and architects Kevin Mitchell and George Katodrytis and the Sharjah-based art historian and independent curator Ali MacGilp respond to "V is for Vacuum", "T is for Territorial", "S is for Symbiotic" and "B for Baroque" respectively.

Al Mazrooie and Abdul Jabbar’s project may appear deceptively simple, but it represents a form of photo-urbanism that not only reveals the complex relationship between landscape, identity and place, but also identifies the road as one of the few places in the UAE to provide a sense of shared experience.

In a country of strangers, the E11 may mean different things to different people – a means of communications and of transporting goods, a route to work and a route home – but it also brings people together, if only as a common point of departure.

As such, the road conforms to the definition of landscape put forward by the American writer John Brinckerhoff Jackson: "a composition of man-made or man-modified spaces to serve as a infrastructure or background for our collective existence," as he explained in his 1984 book, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. "It reassures us that however strange the landscape may appear to be it is not entirely alien."

By foregrounding the everyday and making the spaces and structures associated with the E11 visible, the CAD project also builds on a rich tradition in architectural and landscape history that relies on the use of still and moving images as a vehicle for spatial research.

The American photographer Robert Adams's pictures of suburban Colorado, The New West (1974), belongs to this tradition, as does John Betjeman's sedate journey from 1968, Marble Arch to Edgware, in which the poet used a double-decker bus to explore the history of urban development along London's Edgware Road.

__________________________________

For more on the E11:

• How a road in the UAE paved the way for politicking and national identity

• Time Frame: The E11's humble beginnings

• The UAE's longest road has many names

• Ghantoot offers a safe haven for drivers on E11 between Abu Dhabi and Dubai

__________________________________

Closest of all to the CAD's E11 project however, is the recent work of another individual who trained as an architect but then prefers to understand and analyse the world around us rather than to build.

The English filmmaker and academic Patrick Keiller trained at the Bartlett School of Architecture, part of the University of London, but then embarked on a series of exploratory films – culminating in London (1994), Robinson in Space (1997) and Robinson in Ruins (2010) – which embody Keiller's belief that images of buildings and the landscape have a transformative potential that is not unconnected from political and economic change.

“The present day flaneur carries a camera and travels not so much on foot as in a car or on a train,” Keiller wrote in his essay The Poetic Experience of Townscape and Landscape.

As a description of Al Mazrooei and Abdul Jabbar’s two-year odyssey along the UAE’s longest road, Keiller’s comment could not be more apt.

“Everyone who inhabits a space reacts to it and has an opinion about it and I think that individuals in the discourse [of architecture] need to understand that it isn’t only about material and light,” Al Mazrooei insists.

“It’s also about individuals and their feelings, but that’s something that seems to have been completely lost in the way that we build now.”

• To register for the talks launching the Centre for Architectural Discourse at Nadi Al Quoz (Warehouse 90, Alserkal Avenue, Dubai) on Tuesday October 4 and Wednesday October 26, from 7pm to 9pm, visit www.alserkalavenue.ae or email nadi.al.quoz@gmail.com

nleech@thenational.ae

Nick Leech is a feature writer at The National.