Ahead of his concert tonight in Dubai, the famously belligerent ex-Stone Roses frontman talks to Stephen Dalton about his new album, his gentler outlook on life and his feelings towards his former band However high he climbs, however far he falls, Ian Brown will always have a special place in the pantheon of British music. Although he owes his national-treasure status to his glory years with The Stone Roses, Brown has now been a solo artist for longer than he spent fronting the Manchester indie-rock legends. He has also been far more prolific and musically adventurous during his post-Roses career, launching his sixth studio album this week with a one-off show at Dubai's Madinat Arena tonight.

In the flesh, Brown is lanky and blade-thin, his face all deep hollows and sharp angles. The 46-year-old singer gave up alcohol a decade ago, and keeps in shape by running and doing karate. There may be grey stubble around his cheekbones nowadays, but the gruff-voiced charisma and aristocratic swagger remain intact. Brown still looks like a star. Our interview takes place in London, where the singer lives with his wife, Fabiola, and their son, Emilio. But he still keeps a home close to Manchester, where he regularly visits his two teenage sons from a previous relationship. The great northern capital of British pop remains close to Brown's heart, and he has worked with numerous local legends during his solo career, including the Oasis guitarist Noel Gallagher, Paul Ryder of Happy Mondays, and Andy Rourke of The Smiths. He recently announced plans to write the soundtrack to a forthcoming TV drama series with the ex-Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr, a former childhood friend who lives nearby in the city's leafy southern suburbs.

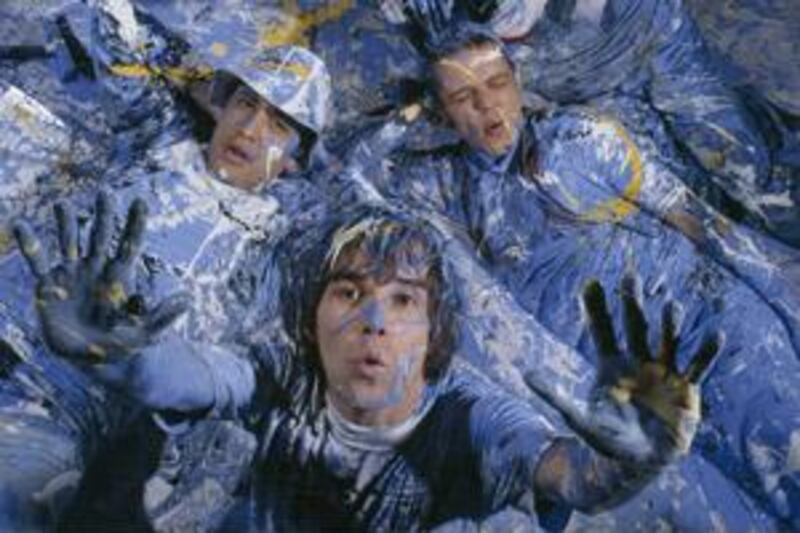

"There was something about the old Manchester that seemed to breed a lot of great music," Brown says. "It was pretty rundown, and combined with all the rain, you definitely had to imagine the sun and imagine great things. Also the dole culture was important. From punk rock through The Smiths, the Roses, the Mondays and Oasis, we all came off dole culture. That's dead now, so it makes it a lot harder." Brown even shot the video for Stellify, the first single from his new album, My Way, on the streets of Manchester's city centre. The album is receiving mixed reviews, but it is unquestionably one of Brown's finest releases, and perhaps his best. With its futuristic funk-rock grooves, shimmering electronic textures, Mexican mariachi trumpets and sermon-like lyrics, it inhabits an exotic musical space beyond the reach of most modern pop. Brown is rightly proud of the album, and characteristically willing to blow his own mariachi trumpet about it.

"I think it's my best in every way," he says. "The best beats, the best melodies, the best lyrics. It's the smartest. All the songs can be played on an acoustic guitar and they'll still stand up. It's got the best sound. The one thing I do on every album is try and make it contemporary, like it could only have been made this year." Brown's last album, 2007's The World Is Yours, was awash with angry diatribes against global injustice, especially military intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan. But My Way is a much more mellow work, largely reflecting on personal issues.

"On the last record I was taking on what I consider to be the wrongs and the ills of the world," he says, "so I wanted to bring this one right back round to myself. It's more of a musical autobiography. I thought I'd just sing things to people, rather than writing it down. I could connect better that way." Unfashionably, Brown is optimistic about the youth of today, a sunny sentiment that informs much of My Way. "Fatherhood makes me more positive for the future," he says. "My kids' friends are 17, 13 and nine, and they are so smart. They've just got a great, positive attitude and that keeps me happy. They don't get into the dark side. It's adults that like the dark side."

Brown has long been infamous for his blunt-spoken belligerence, but he is also motivated by fiercely egalitarian principles and disdain for the celebrity circuit. Raised in a proudly socialist, working-class family in the Manchester suburbs, his childhood heroes were Muhammad Ali and Bruce Lee, while two of his biggest musical icons are Bob Marley and Michael Jackson. He has even covered a handful of Jackson songs - indeed, his wildly ambitious blueprint for My Way was to make an album as good as Thriller.

Jackson's death left Brown with mixed feelings. "It was sad but I kind of did all my grieving back in 1993, when all the allegations about paying off kids came out," he says. "That was pretty devastating because I actually loved what he was, what he stood for and what he did." Brown's reputation has taken a battering since The Stone Roses hit their early 1990s peak as untouchably cool, self-appointed heirs to The Beatles. The band's suicidal swansong performance at the 1996 Reading Festival is now remembered chiefly for the singer's rough, tuneless bellowing. The launch of his debut solo album two years later was overshadowed by an ugly air-rage incident that led to four months in jail.

But whatever his flaws, Brown remains an icon and inspiration to generations. Noel Gallagher has claimed many times that Oasis would never have existed without The Stone Roses. Brown pays homage to Oasis in return, and is philosophical about their recent split. "They had a great run," he shrugs. "It's just a shame when you wash your dirty linen in public. I spoke to Noel the other day and he said that if he'd sat down and thought about it, there's actually nowhere else to take it anyway. They took it further than anyone since The Beatles."

Brown is weary of constantly being asked about his former band, but the subject is hard to avoid on My Way. He mentions The Stone Roses by name on For the Glory, while Always Remember Me is a defiant rebuke to his former childhood friend John Squire, the guitarist whose surprise departure sabotaged the Roses. Estranged for 13 years, Brown has been nursing his wounded pride ever since, although he claims to be indifferent.

"I don't care, mate!" he insists. "The guy left the band, walked out, told me he was giving up guitar, then turned up the next day announcing his new band. If that's how he feels about me, I just don't care. It's like I was 16 and a girl dumped me. But I got over it, I'm not spending my whole life pining." Squire recently attempted to make peace with Brown by sending him the guitar melody for a possible collaboration on My Way. He liked the tune, but refused to use it on principle after his son reminded him that Squire had let him down years before. "He said, 'He left you for dead, why do you want to give him any glory?'" the singer recalls.

After all these years, of course, Brown could simply forgive Squire and move on. "I've not got anything to forgive him for," he shrugs. "I actually think he did me a big favour, because I've had an amazing 12 years. I've done six albums, a greatest hits, I've played in 36 countries solo. If I did run into him on the street I might shake his hand and thank him for it. I didn't realise that the day after the split, but I know that now."

Over the years, The Stone Roses have been offered huge sums for a reunion tour. As the 20th anniversary of their eponymous debut album loomed earlier this year, commemorated by deluxe re-issues, the British press was ablaze with rumours of comeback concerts. Once again, Brown shoots the idea down. "I don't look back, ever," he says emphatically. "The Roses were special to people who were there back in the day. They'd hate to see you go onstage and blow it. We could get amazing amounts of money to do it, but I just don't see that being in the spirit of what we did. I would have been a banker or stockbroker if I'd just wanted to collect money."

After 25 years of highs and lows, Brown seems serenely untroubled by past mistakes or wrong turns. "Je ne regrette rien, monsieur," he laughs. "No regrets at all. I used to think it was all about the Roses, but now I really do think this is my destiny - to do it on my own."