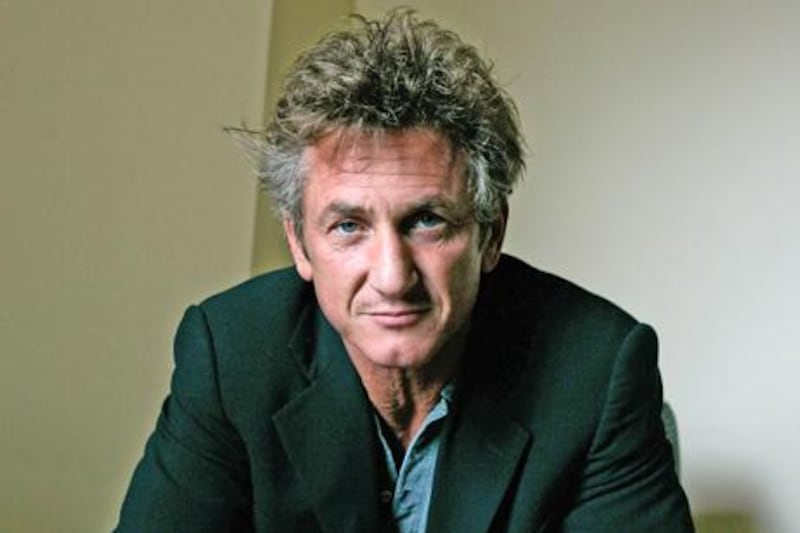

Sean Penn is a man who accepts his medals lightly, modestly, with rarely more than a laconic shrug of thanks. This is, in itself, an impressive accomplishment from an actor who stands beside Brando, Nicholson and De Niro in that elite band of two-time Oscar winners, who furthermore owns the complete set of Best Actor trophies from the world's premier film festivals, Cannes, Venice and Berlin.

But then Penn has always had broader horizons and higher goals in life than the ritual of Hollywood backslapping, his sceptical philosophy closer to that of his late friend Marlon Brando. As Penn once told me: "Marlon said, 'Do you imagine people sit around in tribal cultures and say, 'Here's to Johnny. He killed that bear. I don't think anybody's ever killed a bear quite the way Johnny did...'?" On top of his dislike for turning art into a contest, Penn can usually find livelier ways to spend an evening than climbing into a tuxedo.

In the eyes of the movie-going public and mainstream America, Penn remains an enigma: twice-divorced, reputedly short-fused, strangely antagonistic to his own celebrity. Still, he has been in movies for 30 years now, and for at least half that time has been rated by his peers as America's finest actor.

As such, this year's Dubai International Film Festival has made an astute choice in honouring Penn with its opening night Lifetime Achievement prize. But the truly intelligent decision of the festival is to applaud not only Penn's cinematic work but also his outstanding track record of humanitarian endeavours. As the chairman Abdulhamid Juma, puts it: "His use of the celebrity spotlight to assist humanity is an example to us all."

It is not as widely known as it might be that Penn has spent most of this year in Pétionville, Haiti, a suburb of Port-au-Prince ravaged by January's dreadful earthquake. There Penn runs a camp for some 55,000 displaced people under the banner of the relief agency J/P-HRO that he founded with philanthropist Diana Jenkins. And for much of 2010 he has been neck-deep in the chores of rubble removal, construction, delivery of medical supplies and struggles against such menaces as malaria, diphtheria, and cholera. Penn describes himself as a mere "functionary", but his efforts have been widely acclaimed by veterans of heavy-duty aid work. Of a special commendation he received from Lieutenant-General Ken Keen of US Southern Command, Penn was moved to say: "It meant more to me than any movie award."

This side of Penn's character has declared itself powerfully in the decade since I began writing his authorised biography in 2001. Back then it was already clear he was the foremost American actor of his day. (As Jack Nicholson phrased it for me, "Really good actors, if the time came, they could play their own grandmother, and Sean's one of those.") Just picture the gallery of Penn's prizewinning roles - the barely reformed Boston hoodlum of Mystic River, the gay activist-politician in Milk, the tattooed rapist-murderer of Dead Man Walking, the heart-sore college professor in 21 Grams - and Penn's ability to inhabit a character's skin begins to amaze.

The son of actors and a fiercely committed drama student from his teens, Penn has always worked at his craft, researching his roles fastidiously. But underpinning the skill-set, Penn has a voracious commitment to living in full, not wasting one moment to find out things for himself. His is an open-hearted appetite for life.

Such a man was never going to be fulfilled by film acting alone, which is why Penn's career has been punctuated by sojourns (even retirements) away from the screen. Directing has been his preferred mode of creativity, one in which he excels. (See his three brilliant pictures as writer-director, The Indian Runner, The Crossing Guard and Into the Wild). But political engagement has always called out to Penn, especially so after he became a parent in the 1990s with his second wife, Robin Wright. As he phrased it in 2008: "You need to do it for your kids because you don't want to answer them that all you did during this generation of war was get on MySpace and go to work."

Penn's late father Leo was a special inspiration: a decorated Second World War veteran, actor and lifelong socialist unjustly maligned in the 1950s-era witch-hunts of suspected communists. Penn sees "patriotism" as a virtue exemplified by active service rather than conspicuous flag-waving, and as a man who has always anchored his opinions on what he has himself witnessed and experienced, it was always likely he would be fully engaged in politics.

Thus in 2002/3, having publicly challenged President George W Bush over the motive for the invasion of Iraq, he twice visited Baghdad so as to immerse himself in the unalloyed opinions of the Iraqi street. A taste for the job of investigative journalist next led him to Iran, where he covered 2005's dubious presidential election. Later that year, after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, Penn pitched himself into the hellish aftermath; and in becoming a crisis-volunteer, he found another calling.

As Penn has told me, his activism/volunteerism is "a learning process that I find very stimulating. And it all feels like one thing to me - that or the moviemaking, it's all just part of responding to the unfolding world that I'm seeing, in the little time I've got..."

Penn's relentless drive through life is such that he could make any of us feel we do far too much sitting on our backsides. That he has maintained the power of his acting amid all else is a small miracle. Lately he has specialised in collaborations with visionary directors whom he admires hugely, such as Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, with whom he made 21 Grams, and Paolo Sorrentino, for the recently completed This Must Be the Place.

When I visited Penn on the set of the Sorrentino picture in New York, I found him creating his character - a retired Goth rock star - with typical rigour. Yet in breaks from shooting he was deeply absorbed in reports from his Pétionville camp, and itching to return. His every move in Manhattan was dogged by paparazzi, and Penn's contempt for the celebrity snappers has hardly altered since the mid-1980s when his first marriage to Madonna was spent largely defending her from intrusive goons swinging cameras. However, Penn at 50 is an expert at filtering out distractions, and has the reputation of a man not to be messed with. (The tough-guy renown is partly why it may be too late to convince the public that Penn in private is incredibly funny, quite devilishly quick-witted.)

Thankfully, Penn's humanitarian work is being recognised fully and properly. He is - for what this is worth - as staunch and honourable a man as I've ever met. He instinctively recoils from such praise, prefers to cite people he's met in tougher corners of the globe, unsung heroes who fight the good fight against poverty and injustice without recognition. Still, in the course of his brilliant career he has learnt how to accept a compliment. And another fully merited one is coming his way tonight.