In May 1860, a tribal feud between Maronite Christian and Druze communities near Beirut soon escalated into a wider conflict that ravaged the entire border area between Lebanon and Syria.

In just three days, 60 villages were said to have been destroyed and by July 9 the bloodletting reached its chilling nadir in a three-day pogrom in which Turkish soldiers and Druze and Sunni paramilitaries reportedly killed thousands of Christians in Damascus and razed the city’s ancient Christian quarter to the ground.

Nobody was sure just how many people had died in the 1860 Druze-Maronite Massacre but contemporary estimates put the death toll at anything between 7,000 and 20,000 and the number of displaced refugees at closer to 100,000.

The torrent of violence provoked an international outcry, the dispatch in August 1860 of a 6,000-strong French peacekeeping force and the formation of an international commission, in October 1860, whose aim was to discover the causes of the conflict and to secure future peace.

It was into the aftermath of this religious and diplomatic maelstrom that an unlikely party rode in April 1862, a party that included a prince, a bodyguard of 50 Ottoman cavalrymen and the 42-year-old architectural draftsman-turned-photographer, Francis Bedford.

Bedford was one of eight “gentlemen” who had been selected to accompany the prince in question, Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, on a four-and-a-half-month tour of the Eastern Mediterranean that would take in the major sites of Egypt, the Holy Land, Turkey and Greece.

The prince’s other companions included his guardian, Major-General Robert Bruce, the leading theologian Canon Arthur Stanley, the prince’s equerries Frederick Charles Keppel and Christopher Teesdale VC, and the civil servant Robert Henry Meade, who served on the tour as the groom of the prince’s bedchamber.

Both Stanley and Meade had extensive experience of the Middle East, as the Canon had already toured Egypt and the Holy Land in the winter of 1852-53 and Meade had served as a negotiator with the Druze on the 1860 commission that had investigated the causes of the recent massacre.

As with “Bertie’s” earlier trips to Italy in 1859 and North America in 1860, the Middle Eastern excursion had been devised by his father Albert, the prince consort, ostensibly as a means of completing the 20-year-old’s education.

However, it also served as an invaluable introduction to the issues, regions and rulers he would have to deal with when he eventually became king, including the emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, the German-born royalty of Greece, the viceroy of Egypt, Said Pasha, and the Ottoman Sultan Abdulaziz.

Bedford was assigned official photographer, the first and only one to accompany a tour by the British royal family in the 19th century, and it was in this capacity that he recorded the remarkable scenes of devastation that greeted the royal entourage in Syria where, unlike in Egypt and Palestine, the ruins were still new.

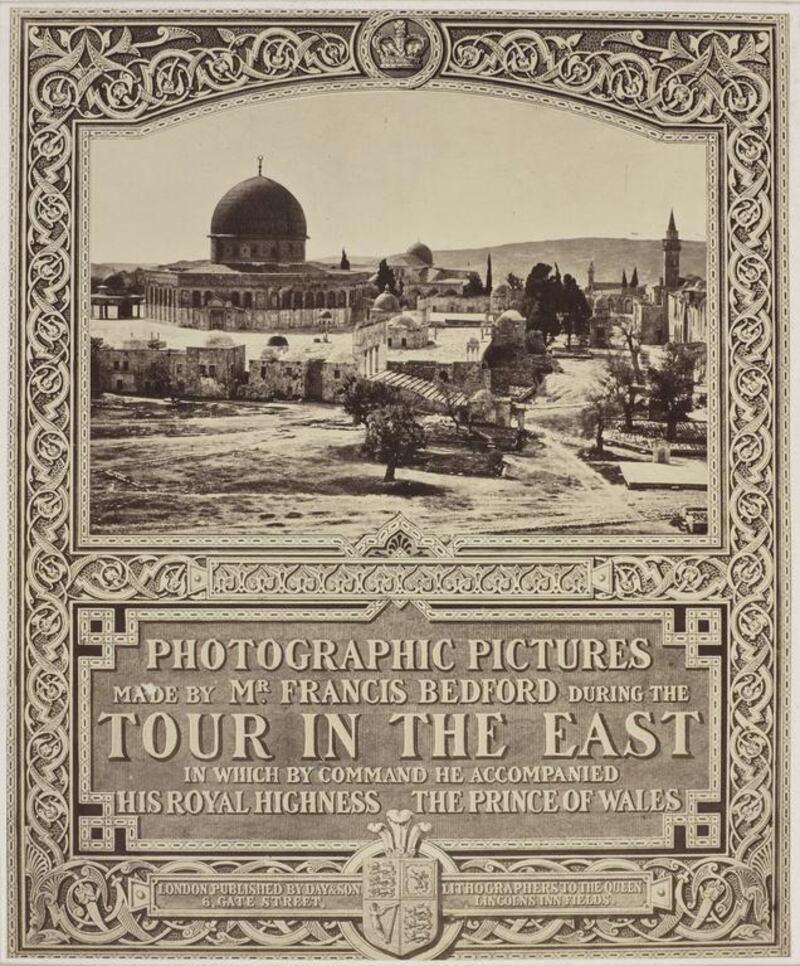

At the time, some of Bedford’s most notable successes were in securing permission to enter the Haram Al Sharif in Jerusalem and to photograph the Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa Mosque at close quarters, but it is his images of the aftermath of the 1860 massacre that capture the contemporary imagination most.

On April 26, 1862, Bedford visited a former Maronite village on the road to Damascus whose still empty houses and abandoned citrus groves he captured in the deceptively picturesque photograph Hasbeiya, Scene of the Massacre. Four days later he recorded the chilling emptiness of the ancient Christian quarter of Damascus in photographs such as The Street Called Straight and Ruins of the Greek Church in the Christian Quarter.

Bedford’s appointment may have been unprecedented but it was not entirely unexpected as the photographer had already endeared himself to the British Queen.

“In 1857, Queen Victoria commissioned Bedford to go to Coburg in Germany, which was the place where Prince Albert had grown up, to take photographs of the landscapes and buildings he would have been familiar with as a child,” explains Sophie Gordon, the senior curator of photographs for the Royal Collection Trust. “The photographs were a surprise birthday present for Albert from the Queen.”

On his return to London, Bedford created an album of views and childhood scenes and the gift was such a success that Victoria asked him to go to Gotha, the other place in Germany that Albert was connected with, to take photographs for the prince consort’s birthday the following year.

Unfortunately for Bedford, the photographs that resulted from his third royal commission were not such a success.

Soon after his return from the Middle East, Bedford displayed his photographs at the German Gallery on London’s Bond Street in an exhibition that charted the four-and-half-month-long expedition. Bedford’s extraordinary prints included views of the Sea of Galilee, the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem but despite receiving critical acclaim they failed to sell in any numbers.

“The series as it was presented for sale consisted of 172 photographs that could be purchased as single prints or in four volumes. The albums were divided up geographically and each had its own title page,” Gordon explains.

“As far as we can tell, very few complete sets were ever sold but the Prince of Wales acquired two that contained extra prints that weren’t available to the public, including some of the group portraits.

"Some of the images are published in The Illustrated London News and turned into engravings and some are reprinted in other books about the Middle East, but the sense that I get, particularly when you consider the number of prints from the tour that have survived to today, is that they were quickly forgotten."

Tellingly, when the Prince of Wales returned to Egypt in 1869 with his wife, the Princess Alexandra, Bedford was not invited and the royal couple travelled with an artist but not a photographer. Gordon believes the omission was more a matter of the medium than the photographer.

“In 1862, I think photography was sufficiently unexplored for the royal advisers to have thought that it would be a good idea without being certain of what the results would be. By 1868-69 they knew what photography was and they realised both its strengths and its limitations.”

Despite those limitations, Bedford succeeded in making a fortune from his architectural and topographical views of the British Isles, which he reproduced and sold in a variety of forms as books, stereographic images and cartes de visite to Britain’s expanding and increasingly leisured middle classes. For Gordon, their popularity is no mystery. “One of the things that we’re trying to do with this book and the exhibition is to revisit this work and say: ‘Look, it’s really good and deserves some attention.’ Francis Bedford may have been largely forgotten but for me he is, alongside Roger Fenton, the leading British photographer of the 19th century.”

• Cairo to Constantinople: Early Photographs of the Middle East will be on show at The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London until February 22. For details, visit www.royalcollection.org.uk

Nick Leech is a features writer at The National