Just because the year's other filmed fight club (The Wrestler) is getting all the awards-season attention right now - and for all the right reasons - doesn't mean that this featherweight underdog should be taken lightly. David Mamet, the playwright by day, laureate of the celluloid underworld by night, has brought his A game to his version of Le Samouraï, Jean Pierre-Melville's brooding gangster study.

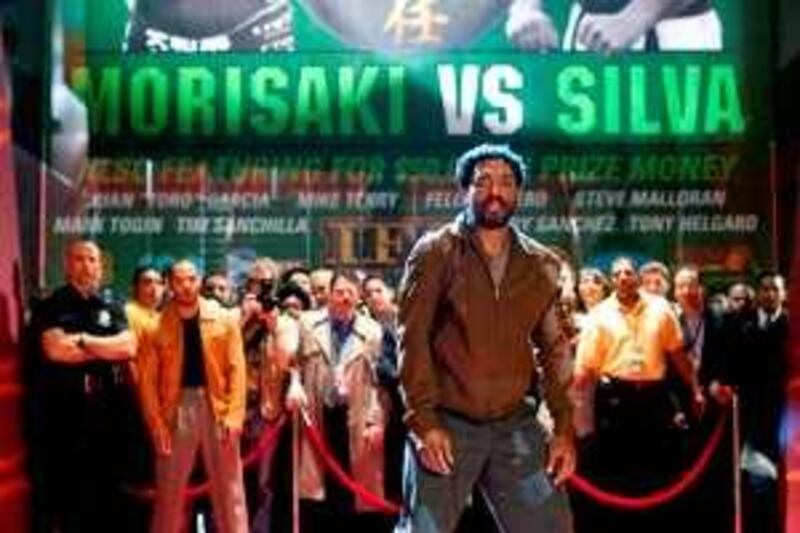

A solitary samurai in the figurative sense, Mike Terry (played by the ever-excellent Chiwetel Ejiofor) is a Gulf war veteran and ju-jitsu instructor. He runs a Los Angeles martial arts academy. He both teaches beginners' classes and trains police officers. He has sad eyes and a strict code of honour. He finds competition distasteful - shameful in fact - which pits him against the American dream, as he is pushed from all sides to go for the jackpot in the ring.

Already with serious money troubles, much to the chagrin of his wife, a textile designer played by Alice Braga, Mike becomes embroiled in a grave financial situation, following an accidental shooting at the academy involving a nervy attorney (Emily Mortimer) and a bar brawl that implicates the ageing Hollywood action star Chet Frank (Tim Allen). Of course Mamet being Mamet, a con has to be involved. In his stage work (Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo) and his screenplays (House of Games, The Spanish Prisoner), he has repeatedly proven that he knows how a con trick ticks better than any other dramatist out there. Here, there's even a movie-within-a-movie motif descended straight from Shakespeare that throws light on otherwise shady dealings.

It seems that Mamet, who studied ju-jitsu for five years (which makes for a fascinating featurette as part of the DVD's extras menu), is more interested in the idea that higher understanding will defeat duplicity. I won't delve further into this film's plot points, partly because much of the pleasure of a Mamet text derives from the curveballs he throws at you, but partly because the curveballs are a little too far-fetched to withstand such a summary. Suffice it to say that events take elaborate turns - so much so that viewers will not be sure if Mamet will pull off his usual coup de grace. (Have faith: he does.)

As shot by Robert Elswit - coming off last year's much-deserved Oscar win for his stunning visuals on Paul Thomas Anderson's There Will Be Blood - Redbelt possesses a crisp urgency that cuts through its writer-director's staccato style and is well rendered in the small-screen transfer. Here his choices are no less theatrical than those that provided Anderson's epic its potency - and that's a very good thing. Elswit lenses the fight sequences and scenes of verbal sparring alike; panoramas of corporeal abuse are equated with two-shots of conjuring deception.

This is a story of another kind of fight altogether: commitment to truth versus compromised principles. Though I'm not sure how well this holds up. The subplot is simply too contrived. For a study of discipline, Redbelt is altogether disorderly.

But it's worth duking it out: the final minutes are like a mime - it's gripping stuff, more of a satisfying endgame than you would expect from a film with such second-act convolutions. "Competition is weakening," Mike imparts to Chet as a way of helping him realise why honour comes above all else in this world. Of course, he never does. But we might: perhaps it was never intended for Redbelt to vie for awards glory. Mamet's film is no smoke and mirrors show.

afeshareki@thenational.ae