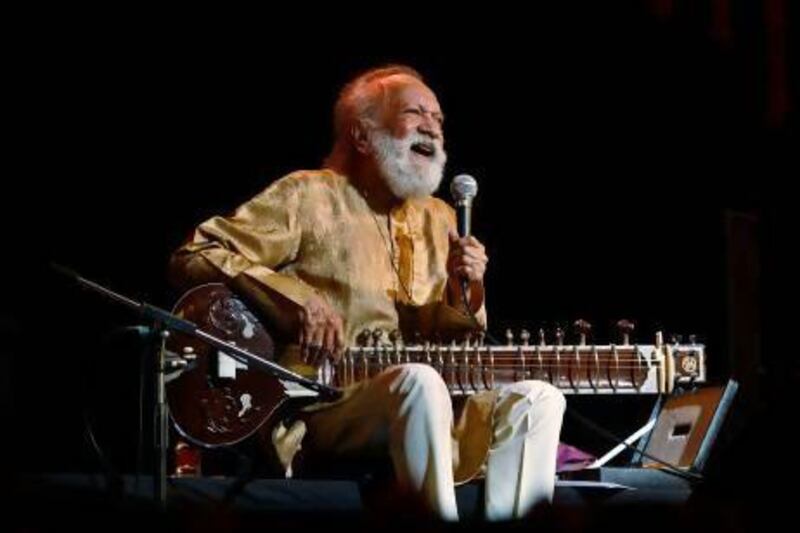

In the 20th century, no Asian musician bestrode the world like Ravi Shankar, who coaxed from his sitar music that brimmed with emotion and that spoke to the breadth of human experience.

His imprint is everywhere: in the film scores of Satyajit Ray and Richard Attenborough, in the music of The Beatles and The Doors and John Coltrane, in collaborations with Philip Glass and André Previn and Yehudi Menuhin, and in sprawling orchestral works created specifically for the sitar.

In this way, he brought to the rest of the world the techniques and joys of Indian classical music: disciplined in its adherence to the scales of a raga, yet fluid and with improvisations within the raga, embodying the teeming imagination of the subcontinent.

Shankar, who has suffered intermittent respiratory and heart problems for the past year, died yesterday in California at the age of 92. He is survived by his wife Sukanya Rajan and by his daughters Norah Jones (from a previous relationship) and Anoushka Shankar, both renowned musicians in their own right.

Only a week ago, Shankar's album The Living Room Sessions Part 1 was nominated for a Grammy for Best World Music Album, in the same category as his daughter Anoushka's album Traveller.

Born into a Bengali family in Varanasi, Shankar began his artistic career early. By the time he was 13, he had already toured Europe with the dance troupe led by his brother Uday Shankar.

He learnt to play an eclectic range of instruments during these tours, but he began to focus on the six-stringed sitar only at the age of 18, when he moved from Paris to the central Indian town of Maihar and studied under the maestro Allauddin Khan.

His guru, Shankar recalled in a 1971 documentary called Raga, "would always say to me: 'In this life, you must do one thing and one thing persistently. But you, you are like a butterfly. If you want to learn music, you must leave everything else.'" Shankar stayed with Khan for seven years. "He was a tyrant absolutely … [But] what he gave me is all my life."

Within India, Shankar enjoyed a rapid rise to fame. He became the music director of All India Radio at the age of 29 and he had already started composing scores that drew upon his rigorous classical training under Khan and his experience with western music.

He was nothing if not musically nimble. In 1948, when asked to play live on radio a tribute to Mahatma Gandhi, he made up a raga on the spot, stressing the notes Ga, Dha and Ni - from the syllables of Gandhi's name - and improvising with them. He named the raga Mohankauns, after Gandhi's first name, Mohandas.

Shankar had already toured extensively in the West and recorded several albums before The Byrds encountered his music. In turn, they introduced Shankar's music to George Harrison, kicking off a friendship that would last until Harrison's death in 2001.

Before Harrison's interest, sitar music left the American audiences "receptive but occasionally puzzled", as Time magazine noted in 1957. But after Harrison taught himself the sitar and played it on the hit Norwegian Wood, and after he trained under Shankar in England and India in the late 1960s, America's interest in Indian music peaked. Shankar called it "the great sitar explosion".

Suddenly, Shankar was in demand everywhere. Robby Krieger, the guitarist of The Doors, enrolled in Shankar's Los Angeles music school. John Coltrane named his son after Shankar.

In 1969, Shankar performed a five-piece set late on the opening day of Woodstock. It was raining. "They were all listening in rapt attention, although I'm not sure if it was induced by marijuana or by the music," Maya Chadda, who played a backing instrument for Shankar that night, told me three years ago.

"But it was received with a standing ovation - well, an ovation, since they were all standing anyway. Raviji that day was like God. Absolutely like God."

Shankar himself, however, would be less than thrilled with the hippie movement that took him into its arms. "So much trash, so much violence," he would say decades later.

Shankar continued to collaborate with Harrison, including in the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh. He lived and worked largely in the United States. "In India, I have been called a destroyer," he said in a 1981 interview. "But that is only because they mixed my identity as a performer and as a composer. As a composer I have tried everything, even electronic music and avant-garde."

Even though he performed and recorded albums well into his 80s, Shankar devoted increasing amounts of his time to teaching.

"He used to think about music 24/7," said Sanjeev Shankar, a shehnai player and one of Shankar's students, between sobs yesterday. "Musically, he was just so giving. I have known so many gurus and they have held back some of their knowledge. He was the one person who never did that. He just gave and gave and gave."

[ ssubramanian@thenational.ae ]