In the past 10 years, cooking has gone glamorous. And all because of two people: Nigella Lawson, the epitome of chic domesticity, and Gordon Ramsay, the razor-tongued professional chef. Lydia Slater examines two very different culinary pin-ups. In the 1970s, feminist Shirley Conran's book Superwoman rallied women with the war cry: "Life's too short to stuff a mushroom." By the time I was a student in the 1990s, the ability to rustle up anything more complicated than beans on toast was taken as proof that one's mind was on a lower plane. Even caring about what you put in your mouth was an indication of unseemly greed. We seemed set on a path towards ever-greater culinary industrialisation. According to the trend predictors, it would only be a few years before meal replacement bars would have consigned the oven to a museum.

How things have changed. These days, it seems life's too short not to be stuffing mushrooms. Far from being considered the basest domestic drudgery, cooking has become a lifestyle choice of the privileged classes. The more time you can devote to it, the freer, wealthier and more creative you obviously are. Our appetite for cookery programmes appears inexhaustible; we read recipe books in bed where we once read novels, and at weekends, shopping for food in farmers' markets has become a prized activity of the middle-aged and middle-class.

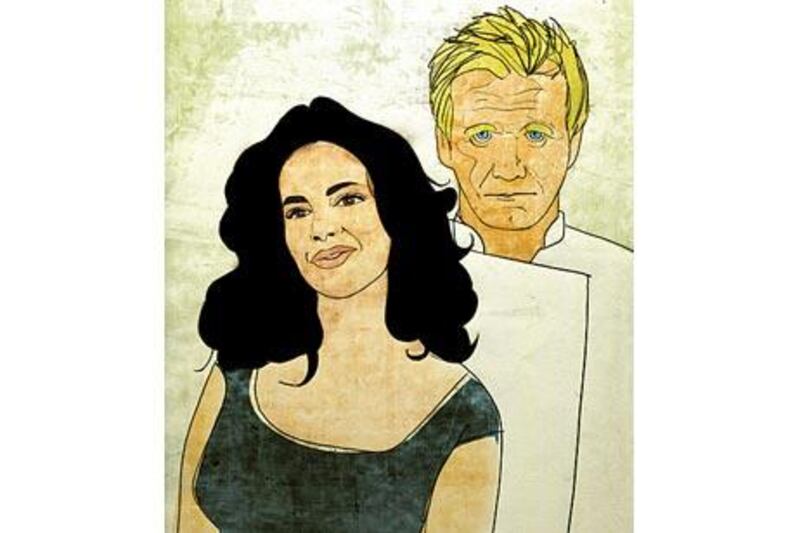

Even those who can't cook now pretend that they can, hence the new popularity of supermarket cook-your-own ranges; home cooking by ingredient assembly. So how did this happen? How did cooking change its image from anodyne to aspirational? The answer is in the almost simultaneous rise to fame over the past decade of two very different culinary pin-ups: Nigella Lawson and Gordon Ramsay. Nigella, 49, is the figurehead for fashionable domesticity. Her seminal book, How To Be A Domestic Goddess, was published in 2000.

Its introduction spelt out what was nothing less than a culinary revolution. "The trouble with much of modern cooking," Nigella wrote, "is not that the food it produces is not good, but that the mood it induces in the cook is one of skin-of-the-teeth efficiency, all briskness and little pleasure. "Sometimes that's the best we can manage, but at other times we don't want to feel stressed and overstretched, but like a domestic goddess, trailing nutmeggy fumes of baking pie in her languorous wake-"

In other words, cooking was not only potentially pleasurable, it could be sexy, too - something that Delia Smith, the mistress of culinary efficiency and briskness, had neglected to inform us. Feminists were outraged by what they saw as Nigella's "retro-misogyny". But the reading public was delighted and her book became a global bestseller. In the same year, she appeared on television in the UK in her first series, Nigella Bites. Curvaceous and cashmere-clad, she dipped her fingers in her sauces and uttered moans of pleasure in her husky, posh voice as she sucked them.

Her raven tresses were not tucked away under a hygienic chef's cap, they tumbled over her shoulders. Best of all, you caught casual glimpses of her highly covetable lifestyle as she stood at the stove, assisted by her small children Cosima and Bruno. Nigella was brought up in a family which had complicated attitudes to food. Her father, the former chancellor of the exchequer, Nigel Lawson, was very overweight, then shed 30 kilgrams in a single year and wrote a best-selling diet book about it.

Her mother, the heiress Vanessa Salmon, was extremely thin and, according to her daughter, had an eating disorder. She used to feed her children huge meals, which Nigella had to be forced to eat. Domestic tragedy has scarred Nigella's life. Her mother died of liver cancer at the age of 48, her sister Thomasina of breast cancer at 32. And then her husband, journalist John Diamond, was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1997.

So Nigella, whose previous experience of gastronomy had been confined to restaurant reviewing for the Spectator magazine - she has no formal training - retreated into the consoling embrace of food. "Eating is a way of saying I accept that I carry on living, even if I don't want to." The year after her husband's diagnosis, she wrote her first book, How To Eat. By the time she was a TV star, making the nation drool as she stirred her luscious concoctions over the family stove, Diamond had had his tongue surgically removed and was unable to eat at all. He died in 2001 and Nigella married multimillionaire art collector Charles Saatchi in 2003. This heady recipe of glamour and tragedy, with its Cinderella-style happy ending, made her famous around the world.

The books and TV shows proliferated: Nigella Bites was followed by Forever Summer, Nigella, Nigella Feasts, Nigella Express and Nigella's Christmas Kitchen. On television, the Desperate Housewives took over from the Sex And The City girls, who retaliated rather desperately by starting to consume cupcakes as well as Cosmopolitans. And crafting became the preserve of the young and glamorous, rather than pensioners. But it remains to be seen whether, in a recession-hit era, being a domestic goddess retains its gloss. It's all too likely that someone who spends lots of time slow-cooking cheap cuts of meat and making their own clothes is doing it because they can't afford the alternative.

In many ways , Gordon is the yang to Nigella's yin, the other face of the culinary coin. Both are household names, who have produced numerous books and TV series, and both have their own lucrative kitchenware ranges. And both have helped to transform the image of cooking from dull to desirable. But that's where the resemblance ends. Where Nigella made cookery seem like a seductive leisure pursuit to indulge in at home, Gordon, 43, turned it into a dangerous activity reserved for professionals. At its broadest, you could say Nigella sells unsophisticated food to the sophisticated, and Gordon does the reverse.

The titles of his TV shows say it all: Boiling Point, Ramsay's Kitchen Nightmares, Hell's Kitchen, The F-Word. His is a macho world of flying knives, flaming saucepans and red-hot language. Professional chefs are filmed weeping at his impossible demands and cringing under his razor-edged tongue. And Ramsay himself looked as though someone had taken a carving knife to his face in retaliation, until his recent cosmetic procedures, his boyish, Tintin features almost comically folded and creased.

He has infused cooking with an entirely masculine glamour of machismo that makes caramelising carrots look tougher than joining the Marines. As a result, his shows have not only helped increase the numbers of young men going into professional catering, he's made it socially acceptable for men to julienne their veg at home. Gordon aficionados are as easily spotted as the Nigella-ites, though their domesticity is of a very different type. In their heads, they are manning the stoves at an haute cuisine establishment. They wear blue and white striped aprons and invest fortunes in Japanese-made knives, copper-bottomed saucepans and nifty blowtorches for finishing off their crème brûlée, which is why such culinary esoterica is now to be found all over the place. Making dinner will require the use of every single pan in the house. Saucepans boil over, frying pans spit furiously, and a feast of exquisite refinement is eventually served around 11pm, when the guests have fallen asleep. This is cooking as a dangerous sport.

Gordon's own life has been made up of the richest, most lip-smacking ingredients: domestic tragedy and public celebrity, with the added spice of numerous spats with famous names. His father was an alcoholic bully who physically abused his wife. There was never enough money: Gordon recently recalled the terrible meals he ate as a child, because they couldn't afford good food. At 17, Rangers Football Club offered him an escape but the respite was brief. At 19, his football career was washed up because of a knee injury. Instead, he went into cooking because he didn't have enough school qualifications to get into the police. His enraged father branded it a profession "for poofs". To some extent, then, Gordon's entire career has been a rebuttal of that initial insult. He must have breathed a sigh of relief when he finally made it into Marco Pierre White's testosterone-fuelled kitchen at London restaurant Harvey's and discovered that the temperamental chef presided over a brutal regime rather similar to the one he had experienced at home.

The abuse continued in the other great kitchens where he subsequently worked. Cuddly Albert Roux threw a pan of bouillabaisse over him, and the priest-like Joel Robuchon plastered him in boiling langoustine ravioli. No wonder he looks a bit battered. So if he dishes it out, it's because he can also take it. "I've been slapped and kicked and punched. And when the chef shouted at me I listened, took it in and said, 'Oui, chef.'"

Nigella's first forays into television were as a glamorous talking head on literary shows. But Gordon was a renowned chef when he first appeared on-screen in 1999. Boiling Point followed his attempts to set up his eponymous restaurant on the old site of La Tante Claire. Restaurant Gordon Ramsay was awarded the ultimate accolade of three Michelin stars in 2001 and is currently the only one in London thus decorated.

The past 12 months have been Gordon's annus horribilis. Profits at his group of British restaurants have plunged nearly 90 per cent, which he blames on over-expansion, and by snide commentators on his almost perpetual presence on TV screens rather than behind his own stove. There has been a spate of closures and sales recently, from London's underperforming Noisette, to his much-trumpeted restaurant in Paris. The latter was sold to the Hilton hotel chain, which also bought his Maze restaurant in Prague, while Gordon Ramsay at the London West Hollywood in LA was sold to the hotel's owners this year.

But if he gets dysfunctional males into the kitchen, to work off their testosterone beating up eggs rather than each other, then society at large should raise a glass to Gordon. Some day, a new foodie will move from the kitchen to the limelight; my money's on someone who can make vegetarianism alluring.