It takes six weeks to build a 'jingle truck', the brightly decorated lorries that rumble through the city of Peshawar. Adnan Khan meets the men who paint them and discovers how their work reflects the inner lives of the drivers of these massive murals on wheels. 'Think of it this way: when a man gets married, his bride is decorated for him - she is made as beautiful as she can possibly be. For a truck driver, his truck is his bride," says Baqir Khan, a Pakistani trucker.

There's an unmistakable glint in Baqir's eye whenever he talks about his truck. It's as if he's escaping the realities of his life, slipping back into a simpler time when the world around him was a playground and the objects of his desire were full of colour and light. You can see the transformation - from the solemn 24-year-old man, battered and bruised by years of poverty and hopelessness, to an irrepressible child, proudly showing off his new toy. His truck is, of course, no mere trinket, though there is an unmistakable element of whimsy to it. The four-tonne, 207 horsepower Hino rig has been custom built for him, the lifeless machine itself transformed from a mechanical thing to living expression of his dreams.

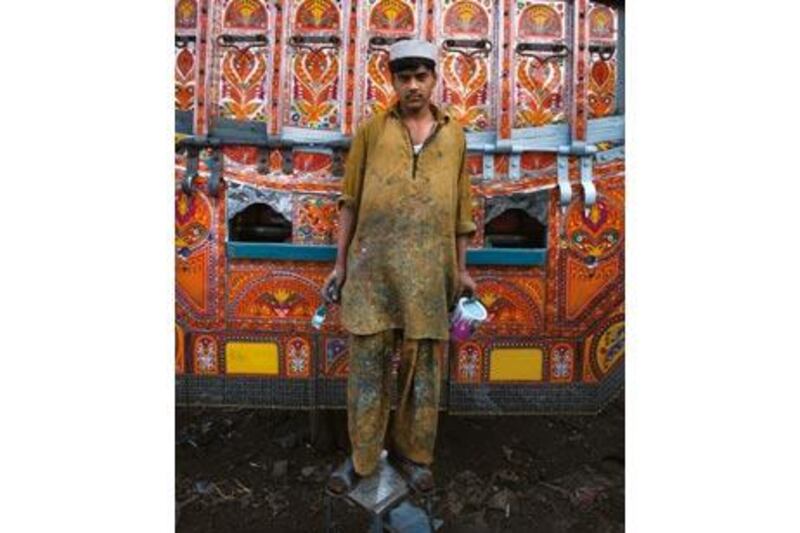

In the noisy yard on the southern outskirts of Peshawar, other trucks are being built for other drivers with similar dreams. The work starts from the basic elements: chassis are stretched and reinforced, the support beams of the carriage carved from massive pieces of wood; cabs, dreary and unremarkable in their original form, stripped bare and reconstructed in shades of lollipop to suit each driver's individual tastes. Painters wait for the carriage to be built and then attack it with their brushes, turning bland metal into psychedelic canvases. After one and a half months of laborious effort, the final product will emerge in all its glory: a massive mural on wheels, dubbed the "jingle truck" by foreigners and considered by Peshawaris to be the one object of pride in an otherwise bleak landscape.

Watching these trucks rumble through Peshawar's anarchic streets, I've often wondered what it is that drives truckers to such polychromatic extremes. I've asked dozens of them why they do it. There is one common answer: it's for the beauty. Simple. But somehow, after spending hours talking to them, I have the sense that there is more to it. Beauty doesn't exist in a vacuum. According to art historians, objects of beauty form a reciprocal bond with the culture that surrounds them, a kind of continuum in which art and society feed off each other.

On the one hand, the meaning of art changes over time depending on the cultural context. Conversely, art production reflects a culture's collective realities - we can learn a lot about what is happening in a culture at a given point in time by studying its art. For drivers like Baqir, a truck is a work of art. "Look at this and you don't need to look anywhere else," he says, spreading his arms wide. "All the beauty you need is there."

Indeed, in a place like Peshawar, there really is no other place to look. Every inch of this riotous frontier city is a case study in urban ugliness. It is a place I can only describe as nauseating - a frenzied mass of dust and noise, crowds and chaos. And there is madness here, the deep, dangerous kind of madness that is the product of war. From day to day no one knows if this will be their last, if today they will step out for a bag of rice and into a bomb blast.

For Pakistanis, the past 30 years have been an era of extreme upheaval. Uninterrupted war in neighbouring Afghanistan, rising jihadi militancy and now conflict on their own doorstep have altered the national psyche, perhaps irrevocably. According to Musafir Baig, a 63-year-old master truck painter, the violent impact of the past three decades has even altered the way in which painters express their art. Lorry painters represent the leading edge of artistic expression in a city like Peshawar, he says. They are the first to be affected by changes in their culture's values and world view, so it's not surprising that truck art was the first to respond to Pakistan's changing fortunes.

Thirty years ago, life was a far cry from what it is today. The Soviets hadn't invaded Afghanistan and Peshawar was still a lively transit point for Europeans travelling the hippie trail to India. Life was simple, and art reflected that simplicity. But after the invasion in 1979, everything changed - simplicity gave way to an eruption of form and colour. No one can say who started the trend, but everyone agrees the change was inevitable. "The times were changing," says Musafir. "The simple life we knew began to collapse around us. The suffering we saw in the refugees coming over from Afghanistan to the camps in Peshawar changed us. It changed everybody."

For the Pashtuns in particular, who dominate Peshawar and the eastern regions of Afghanistan bordering Pakistan, witnessing the violent fracture of their society left a lasting impression, and if art truly does reflect the times, then it was only natural that the way in which painters expressed their inner lives would also change. Musafir is a master landscape painter. His miniature depictions of idyllic meadows and mountain scenery are much in demand in the trucking community. This was not always the case.

"I was never much interested in this type of painting," he says. "When I was young, I painted simple patterns, like arabesque. That's what was in my mind at the time and what was most popular with drivers. But when I paint, I look into my heart and the images that form there come into my mind. Now the images are of these places." It's easy to see a narrative of escape in these tiny renditions of paradise. Set against the madness of Peshawar, they are that much more poignant: Pakistan is a paradise lost - who wouldn't want to escape it? And so much more so for a trucker, whose life is spent negotiating every nook and cranny of this dark world. The truckers will go where others wouldn't dare: they have entered the war zones in Swat and the tribal areas. They ferry Nato and American military supplies through the treacherous Khyber Pass into Afghanistan. The environment they work in is the polar opposite of Musafir's paintings. But when they slip into their cabs, they enter a different world altogether, a world dominated by colour and light.

Baqir's truck is nearing completion. The final touches are being put in place, from the metallic bells dangling on the front and rear bumpers that will give it its distinctive jingling sound, to the panels of red and orange flower patterns that will adorn the top of the carriage. When it rolls out on to Peshawar's congested roads, it will be a thing of beauty, one of the few symbols of creative vigour left in a bleak city.

And it will be an expression of its driver's personality. Like many drivers, Baqir brought pictures with him of scenes he finds especially meaningful - a shot of a favourite mosque and a landscape from Swat that he has driven past many times and loves. They have been added to the more imaginative images on the side panels of the carriage. But the largest painting is devoted to his one true love: a massive portrait of Naghma, one of Pashtun music's best-known singers, adorning the back of the truck. "Naghma is the only singer I listen to when I'm driving," says Baqir. "For me, she is the queen of the road."

The road he's talking about is as much a state of mind as it is a physical entity. When he compares it to a river pushing endlessly into Pakistan's frontier, you see a glimpse of the uncertainty that has become the dominant feature of his life. When he describes his life on the road, the weeks and months, 24 hours a day with his truck, you sense just how elemental this relationship is, how it gives him some measure of meaning and purpose. Then, perhaps, you can begin to understand why drivers like Baqir have their trucks painted.

The art, however, is dying. As with so much else in Peshawar, the endless bomb blasts and chaos are sucking the city dry of its creativity. Tabla-makers are going out of business because, as one master craftsman told me, "Who wants to listen to music in a time of sadness? Music is celebration, but there is nothing left to celebrate in this city." This is the most costly casualty of war: when your day-to-day life is so consumed by the struggle to survive that there is no time for simple pleasures. "Fewer and fewer truckers are having their trucks painted these days," says Musafir. "And we painters are tired of this world. There is nothing left in our hearts to inspire us."

And so they leave. The best of them are sometimes recruited by Arabs from the Gulf, to paint murals in their homes. "A few painters have escaped that way," says Musafir. "None of them has ever come back. None of them wants to come back." But for the drivers, there is no escape; there is only the road. And as endless as those roads may seem, they ultimately must come to an end, somewhere on the distant horizon where borders form the prison that Pakistan has become. And so drivers like Baqir retreat into the dream world of their jingle trucks. There at least, the world has no boundaries.