We probably don’t need to print a spoiler alert here warning you about the tragic turns taken in the tale of Romeo and Juliet. The Shakespeare classic is, after all, the best-known love story ever written, moving millions of readers, viewers and listeners afresh every year – and inspiring countless artists of the stage and beyond.

Away from the theatre, the Bard's play has stimulated creatives across the arts for more than 400 years – from Romantic poetry to pop songs, opera to Bollywood and Pre-Raphaelite painting to Japanese anime. Many of these spin-off works have become household fables in their own right – from the foot-tapping singalongs of Leonard Bernstein's landmark musical retelling West Side Story to Baz Luhrmann's misjudged MTV-inspired blockbuster Romeo + Juliet.

No surprise that the word Romeo has now become shorthand for “male lover” in English.

That such a divergent cast of creatives have all fallen under Shakespeare’s spell says much about the enduring nature and imaginative possibilities of the story’s narrative, of the myriad of emotions and symbols found in these two young, famously “star-crossed lovers”, destined by fate to spend eternity together after dying in each other’s arms.

Too much bloodshed for Prokofiev

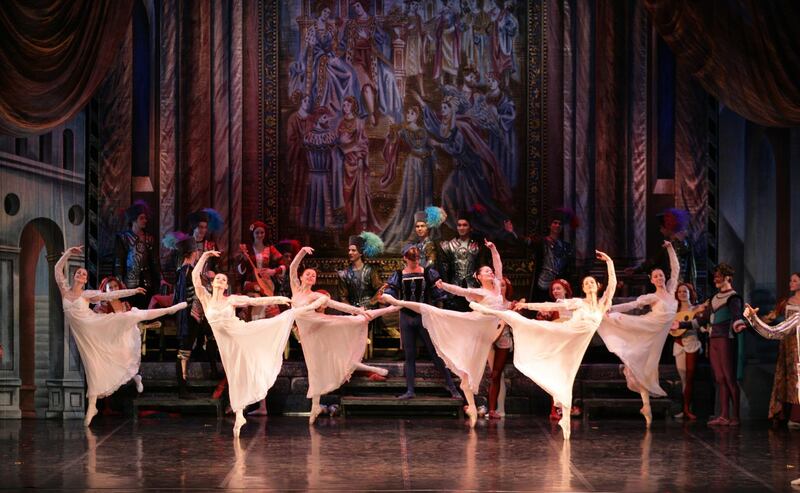

Or not. There was one prodigious artist who found all that bloodshed and heartbreak a bit much – Sergei Prokofiev. In the original version of the Russian composer's classic ballet Romeo and Juliet – to be performed at Dubai Opera, April 19-21 – the couple survived to perform a few pirouettes more, then dance off stage right into the blissful twilight of old age.

Which, it might be said, rather nullifies the crux of what makes Romeo and Juliet the couple they are – without the double suicide, any other pair of socio-economically unmatched lovebirds will do.

Stalin steps in

Turns out that was Josef Stalin’s take, anyway. Unhappy with the happy ending idea, the Soviet leader blocked that commission in its tracks, and Prokofiev’s score was hacked about and reassembled with the traditionally tragic ending. It would be this “Dictator’s Cut” that went down in the canon, and which will be performed in Dubai.

Fittingly the performance comes from the Moscow City Ballet, a group that was founded in 1988 as the first privately owned ballet group in the USSR, and thrived in the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union – the same oppressive regime that butchered Prokofiev's best-loved work.

Our story begins in 1935 when Prokofiev, having fled revolutionary Russia about 17 years earlier for life in the US and later Paris, returned home to Moscow for good. The composer had accepted a lucrative offer to compose a ballet for the Bolshoi Theatre.

After dismissing suggestions to restage Tristan und Isolde and Pelléas et Mélisande – scared off by the masterful versions already penned by Wagner and Debussy, respectively – he settled on Shakespeare.

Working from a synopsis by dramatists Adrian Piotrovsky and Sergei Radlov, Romeo and Juliet was reimagined as a revolutionary flavoured generational struggle and, holed up in an artists' retreat, the composer wrote more than two hours of music in four months. The new happy ending apparently had as much to do with Prokofiev's little-known Christian Science beliefs as it did his collaborators' desires to send the audience off with a swing in their step.

But, in 1936, the establishment of the USSR's ominous-sounding Committee on Arts Affairs led to the liquidation of the entire Bolshoi administration, while the general director who had approved Romeo and Juliet, Vladimir Mutnykh, was executed. Prokofiev had every reason to be anxious; his great rival Shostakovich was quickly denounced, soon leading to the latter's much-discussed, Stalin-placating fifth symphony. Romeo and Juliet was quietly shelved and Prokofiev kept a low profile.

A dramatically edited single-act version of the ballet was eventually staged in the Czech Republic in 1938, a well-received premiere at arms' length, which finally led to an offer from the Kirov to stage the work in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) two years later. There was one catch: the proviso that the "reformed" Prokofiev – who had fled as an iconoclastic proponent of dissonance – adapt his work to better meet the USSR's conservative ideals of entertainment. First among the demands was a reinstatement of the traditional, unhappy ending.

Whether it was fear, ego or pragmatism that led Prokofiev to succumb to the demeaning round of revisions ahead we will never know – he may have been motivated by the simple desire to see at least some of his epic, three-suite score heard by an audience. As well as the ending, the composer made sizeable excisions, re-orderings and was ordered to write a raft of new music to show off the company’s dancers.

What was lost

The full extent of the cuts was not known until seven decades later, when music scholar Simon Morrison discovered the original manuscript in a Moscow archive while researching a book on its composer. In total, he uncovered about 20 minutes of lost music, including six new dances, as well as Prokofiev's original title: Romeo and Juliet: On Motifs of Shakespeare. Eventually, this original version would be premiered as a novelty in 2008, and remains rarely performed to this day.

Stalin's changes

Instead, it was "The Dictator's Cut" audiences came to know and love, after Stalin later wrote a letter officially approving the Leningrad version for performance at Moscow's Bolshoi in 1946 – interpreted as a politically motivated programme to garner postwar favour with British politicians by performing a work inspired by their dearest writer.

And with that flurry of an autograph, Stalin solidified Romeo and Juliet's future, paving the way for one of the most beloved dance works in the repertoire, and setting up its familiar musical moments for decades of light radio play and popular culture appropriation. These most notably include the pompous brass swagger of The Montagues and Capulets – sometimes known as The Dance of the Knights – familiar from multitudes of sports stadiums and TV shows, including the UK version of The Apprentice.

While it is only natural to mourn the revisions Prokofiev was forced to make, we might ponder for a moment the very real world where Romeo and Juliet never made it to the Bolshoi – where Stalin never scrawled that fateful squiggle. And for the fact that he did, music and ballet fans should be eternally thankful.

Moscow City Ballet performs Romeo and Juliet at Dubai Opera on April 19 and 20 at 8pm, and April 21 at 4pm. Tickets from Dh350, see dubaiopera.com

_________________

Read more:

[ Marie-Agnes Gillot – ballet’s most unlikely star takes her final bow ]

[ What tempted the UAE’s ‘first’ ballet star Alia Al Neyadi back to the stage ]

[ Madonna to direct film on Sierra Leone dancer ]

_________________