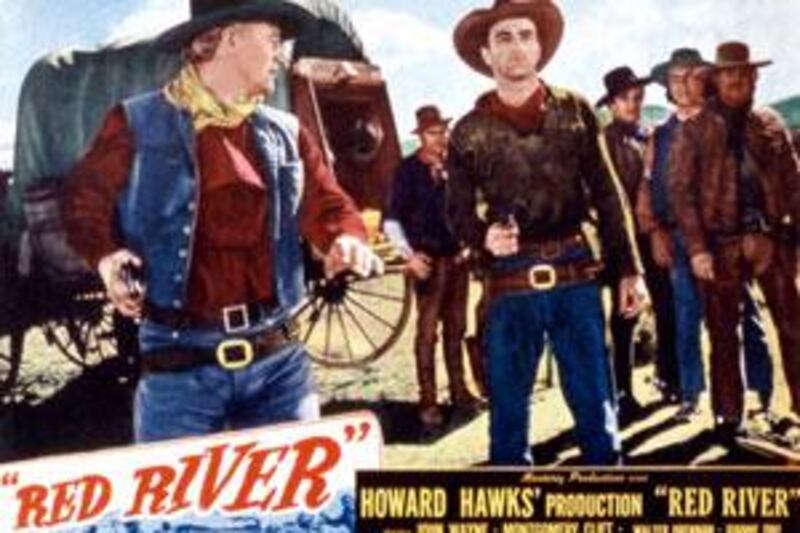

David Thomson has become the world's most celebrated film critic by marrying encyclopedic ambition and an Olympian disdain for the cinema of today. AS Hamrah traces the long arc of his disillusionment. "I once showed Red River on a course for American students," David Thomson wrote in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, back in the pre-blockbuster 1970s, "and at the end - like Charles Foster Kane at the opera - I stood up alone to applaud." For 35 years Thomson's readers have watched him retreat from that moment. In more than a dozen books, in countless articles in newspapers and magazines and online, Thomson's enthusiasm for the movies has drained - not in a trickle but in torrents, like an emptying ocean.

Unlike the horde of cheerleading critics whose hollow praise blights the film pages, Thomson alone has made bitterness a career, mourning Hollywood's decline and fall. A genuine littérateur, he has elevated himself above ordinary movie reviewing in a way someone like Roger Ebert has not. As he's become darker and more defeatist, alienated from the cinema and preoccupied with celebrities and power, he's gained in respect. The Atlantic Monthly calls him "probably the greatest living film critic and historian."

Thomson has seen his Biographical Dictionary, a collection of erudite essays covering everyone from Anouk Aimée to Darryl Zanuck, become a standard reference and an updatable franchise, like Raiders of the Lost Ark. The New York Times Book Review described it as "one of the most probing accounts ever written of a human being's engagement with the movies," adding breathlessly that Thomson's "ambition is to probe nothing less than human illusions."

Accustomed to praise, Thomson is also forgiven his trespasses. His 2006 tome Nicole Kidman, a hymn to the actress in the form of a picky mash note, raised eyebrows. But it was forgotten when the weirdly titled "Have You Seen . . . ?" A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films came out last year, prompting the co-president of Sony Pictures to call Thomson "the foremost film writer of our time." Yet it's the Kidman book, with its fantasies of made-up movies in which Kidman does not appear, along with 2005's The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood, that seem like quintessential David Thomson: high-toned, windy books concerned not with movies or directors but with The System and David Thomson's "personal" fantasy of what it does to people.

Thomson maintains his preeminence by pleasing on two fronts. For literary baby boomers, traditionally suspicious of the movies, he laments the passing of cinema's glory days. For seekers of inside dope, he exposes the spiritual corruption of the blockbuster industry, submitting to its fall as predestined. In his adopted homeland, the USA, the Englishman Thomson spreads pessimism over our illusions like orange marmalade, and he's been thanked for it more than any film critic could expect.

One gets the feeling, however, when reading his books, that no reward is great enough for this chronicler of the movies' decline. His prose exudes a sense of wounded disappointment beyond praise. With the release of his new memoir, Try to Tell the Story, an account of his boyhood and teenage years in London after the Second World War, we begin to see why. Post-war London, as Thomson describes it, looked and felt defeated. He grew up among bombed-out buildings in a nation victorious but wrecked, a lonely child with little privacy in a house shared by three generations and a boarder. Lonely but never quite alone, his childhood was dominated by someone who wasn't really there - not "Sally", the slightly older and wiser girl he invented to be his imaginary friend - but his father, who abandoned his family to live across town with another woman. His desertion, however, was incomplete: he remained married to Thomson's mother, showing up two weekends out of three to live with the family he'd left. Thomson's father hit him, took back gifts, failed to support his decision to study film instead of going to Oxford on a scholarship, and made a point of leaving him nothing in his will.

This unorthodox situation was quietly accepted in the Thomson household. Thomson's father owned the house; his mother lived there, too. As she aged, her daughter-in-law looked after her. Thomson's mother cannot have been happy about her life, but we can't really know. She is a quiet presence in Try to Tell the Story. Thomson acknowledges her absence in a coda. "My mum is not quite there, not like she was in real life. And in a way that is a final mark of dad's influence. That he left us was a gesture that claimed our story as being lived in his shadow."

This is a coming-of-age story that will make sense to other cineastes. Left to figure out the world for himself, the young Thomson turned to movies, jazz and cricket, and his memoir calls back to life the films, music and sports of a London that has disappeared. Many of the best sections of the book deal with movies and music, and that makes sense; Thomson is a critic. His memoir echoes a recent film, Terence Davies's Of Time and the City, a documentary about the director's youth in Liverpool. Of Time and the City is an aggrieved work, narrated in tones of extreme disdain, but in Try to Tell the Story, Thomson for once leaves bitterness behind, to see the past more clearly. Davies stayed in England; Thomson eventually left for America. Even before he went away, Thomson left his past behind by trading his father's shadow for the shadows on the screen.

If Thomson's story is inherently dingy and sad, he takes pains to make it vibrant instead of maudlin. Because he is reliving his first encounter with Hollywood movies, before he was jaded by encounters with the real Hollywood, everything seems fresh. His memoir describes the real melancholy Thomson overcame, unlike the melancholy he sells today as the real tinsel beneath Hollywood's fake tinsel. To quote the Christina Rossetti sonnet that features prominently in Kiss Me Deadly, darkness and corruption have left a vestige of the thoughts that he once had.

Oscar Wilde wrote that "the highest, as the lowest, form of criticism is a mode of autobiography." A film critic's autobiography is the story of his response to certain films. For Thomson, those films were made in Hollywood in the 1940s and '50s, when he was young. Thomson's taste mirrors that of the critics at Cahiers du cinéma who became the Nouvelle Vague. Like them, and in the same years, he loved Citizen Kane, James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, Howard Hawks. Every critic has that one film that changed everything. For Thomson it was Hawks's Red River.

"I remember all these pictures, and many others," Thomson writes, "but nothing was like the experience of seeing Red River... This was the first story I knew was meant for me. So I knew I could not give it up." Right after seeing it for the first time, he stays for a second show. The prolific Chilean director Raul Ruiz writes that when he first saw Edgar Ulmer's 1930s horror movie The Black Cat, for him it was like a father calling to his son: "Now at last recognition came to me, and as in an old melodrama, I exclaimed: 'Father!' and he replied 'My son!'" Quentin Tarantino has said that as a boy growing up without a father, his constant viewing of Howard Hawks films taught him how to be a man.

Let me confess that I, too, was raised by The Big Sleep, To Have and Have Not, His Girl Friday, Twentieth Century and Hawks westerns in lieu of a father who wasn't around. Red River is Hawks's most overt film in this respect. It deals explicitly with the difficult, sometimes hate-filled relationship between a surrogate father, John Wayne, and son, Montgomery Clift. Red River still exerts so much power over Thomson that he refuses to give away the film's ending in his memoir.

I will respect Thomson enough to say only that Red River ends unexpectedly, maturely and happily. John Wayne is absent from much of the film's action, but this father figure haunts every moment of the film just the same, the way art isn't always there in the movies, but the promise of art always is. For young men without fathers, the film fulfills a wish of reconciliation but also shows how fathers can be wrong, dangerous and necessary to remove.

Which is how Thomson seems to feel about movies today. Cinema is a vagrant art and it travels from country to country. Instead of looking for the cinema as he found it in the late 1940s, which meant looking for it wherever it might appear, Thomson kept looking to Hollywood, seeking the same kind of affirmation he got from Red River as child. Is it any wonder he's been disappointed? While Thomson may have worked himself out of a fix by writing Try to Tell the Story, for a long time his readers have had to put up with the soured feelings that got him there. For too many years before this book, Thomson has harrumphed his way through his gossipy prose like he's Colonel Mustard in the billiard room with the candlestick, beating the movies to death in his own personal game of Clue.

"No good American ever seriously questions an English judgment on as aesthetic question," HL Mencken wrote in 1920. Thomson has thrived on Mencken's sardonic axiom. Once he realized Hollywood wasn't going to deliver another Red River, he began telling a certain kind of sophisticated reader what he or she wanted to hear. In the bleak age of the weekend box office gross he reminded us that Cary Grant is spotless, that producers care more about money than the script, that Nicole Kidman is a honey but not getting any younger. Nobody thought otherwise, but it was comforting to hear somebody say it in such a cultured way.

I, for one, will never forget the queasy sensation I felt when I first picked up a copy of his book Warren Beatty and Desert Eyes, another half-biography, half-novel, and read this excerpt on the back cover: "And like any Narcissus, he will keep his looks so long as desire moves him. If that ever goes, if it becomes a mere idea, then youth will be replaced by something like Dracula's haggard smile." It reminds me of the last two lines of that Christina Rossetti poem from Kiss Me Deadly: "Better by far you should forget and smile / Than that you should remember and be sad."

Today David Thomson lives in San Francisco, where he sits in judgment north of Hollywood. Try to Tell the Story returns him, and us, to a more generous time in his life, when he was putting the world together instead of tearing it apart. AS Hamrah lives in Brooklyn, where he is the film critic for n+1.