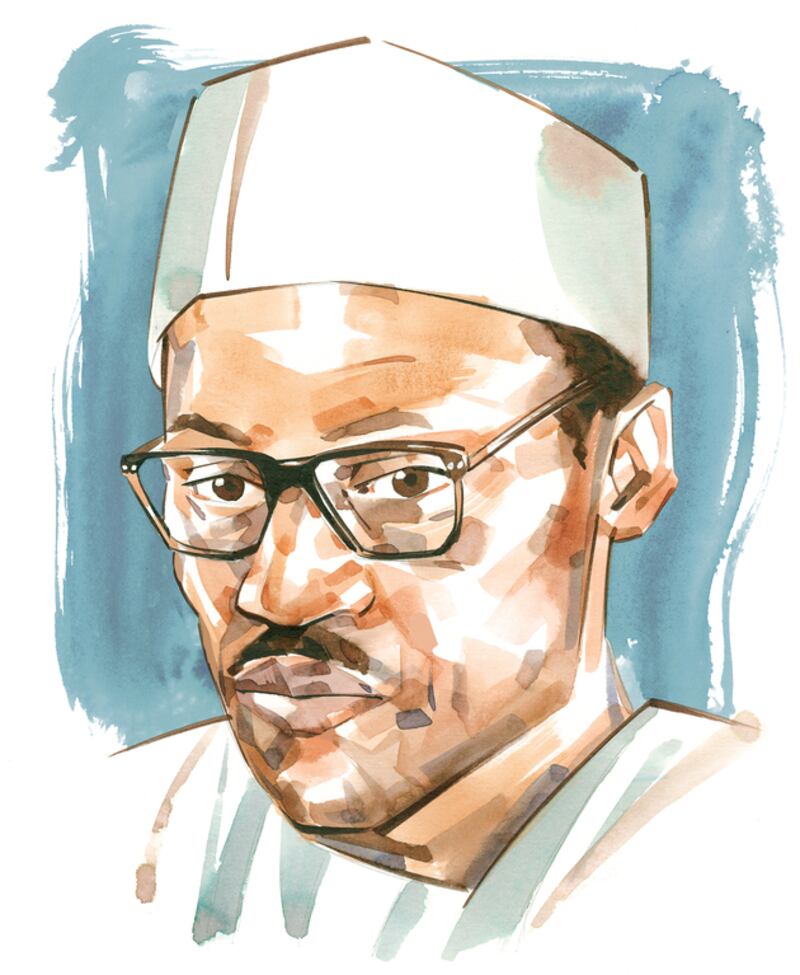

If one word sums up the ethos of Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria’s president-elect after his victory over Goodluck Jonathan in this week’s groundbreaking elections, it’s orderliness.

As he has transformed himself from military ruler to elected head of state, Buhari has proved open to persuasion on weighty issues facing the country with Africa’s biggest population and economy – and some of its worst political turmoil and ethnic violence.

The collapse of the Soviet Union led him to embrace the principles of democracy. He no longer believes Sharia should be applied without exception in a country where the divide between Islam and Christianity is close to 50-50. And he has come to regard Boko Haram, the insurgent group recently allied to ISIL and responsible for repeated acts of merciless barbarity, as “mindless bigots masquerading as Muslims”, promising to wipe them out within months.

But whether reflecting on security threats or encouraging higher standards of personal behaviour, the 72-year-old former major-general is a stickler for order.

However enthusiastically he now champions a more open society, he clings remorselessly to the same sense of discipline he sought to impose on Nigeria during his 20-month spell as military dictator after a coup on New Year’s Eve 1983.

The higher ideal of his rule was to confront the corruption rife in Nigerian society. But human rights were not his strong point: unprecedented powers were granted to the secret police; dissent was remorselessly stifled; there was widespread detention without charge, while those who did come to court were convicted on what Amnesty International described as “spurious” grounds. Press freedom was curbed and strikes and demonstrations banned.

In a rather farcical application of his wish for a more ordered society, his “war against indiscipline” policy led to civil servants, regardless of age, being made to perform humiliating frog jumps if late for work.

Critics say his belief in firm discipline was at times more literal, with soldiers instructed to inflict on-the-spot floggings when passengers failed to queue properly at bus stops.

Twenty years on, Buhari questioned the details of his policy – namely that he had ever ordered whippings – while defending the principle. “There was so much exaggeration,” he told a BBC interviewer, Tim Sebastian, in 2004, after a failed early attempt to become president. The exchange that followed was illuminating.

Sebastian: “You never did that [insisted on disciplined queuing]?”

Buhari: “No. I did not say I did not do it. But I didn’t order for people to be whipped. But if you go ask, we have developed a culture of orderliness in a chaotic society.”

Pressed on why he should concern himself with how people behaved at bus stops in a country with “massive corruption … massive poverty”, he simply repeated that the pursuit of “orderliness” was part of a broader campaign to improve public morality and civic responsibility, which also included trying to stamp out graft.

“It was part of the process of disciplining a society,” he said. “That’s why we have a zonal tribunal where corrupt individuals were being charged and some were successfully prosecuted.”

Now Buhari, representing the All Progressives Congress, has become the first opposition candidate to win a presidential election since Nigeria gained independence from its colonial power, Britain, in 1960.

Whatever reservations Nigerians may have had concerning the past, they showed a clear preference for what Buhari now offers over the perceived failure of Goodluck Jonathan, Nigeria’s president since 2010 from the People’s Democratic Party.

Buhari’s margin of victory was a relatively comfortable 2.5 million (15.4 million votes to Jonathan’s 12.9 million). That still leaves a substantial minority of disgruntled voters, but initial responses from both men were conciliatory.

Buhari praised a “worthy opponent” and his peaceful surrender of power, while Jonathan said: “I promised the country free and fair elections. I have kept my word.”

Buhari is the 23rd child of Adamu and Zulaihat, born in Daura, in northern Nigeria’s Katsina State, in 1942. He was brought up by his mother after his father’s death when he was 3 or 4.

He first married in 1971, fathering five children with Safinatu, who died in 2006, 18 years after their divorce. His first lady on taking office in May will be his second wife, Aisha, with whom he has also had five children.

Buhari enlisted in the Nigerian army at 19, training at the national military college before taking an officer cadet course in England. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1963, serving as an infantry platoon commander before returning to Britain for specialist officer training.

He rose rapidly and by 1978 was a member of Nigeria’s supreme military council. Further promotions followed, and he also gained a master’s degree in strategic planning from a United States army college. As a senior officer, he also took part in the bloody Biafra war that ravaged Nigeria from 1967 to 1970, and there have been allegations of troops under his command committing atrocities. But it was a brutal conflict and few participants emerged with clean hands.

Earlier, in the post-independence turmoil of mid-1960s Nigeria, he took part in a coup, led by Lt Col Murtala Muhammed that culminated in the overthrow and assassination of the military head of state, Gen Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Muhammed rewarded him by making him governor of North-Eastern State. He later served as the Nigerian oil minister and the first chairman of the country’s National Petroleum Corporation, a role that brought him an early brush with controversy when he was accused of complicity in the disappearance of 2.8 billion Nigerian naira (then worth about Dh5.5bn) from a London bank account.

Buhari’s intense anger at the way the affair was reported in the press has been cited as a factor influencing his repressive treatment of journalists on taking power after the coup of 1983. In another scandal, during his time as military ruler, opponents suspected his involvement in the so-called “53 suitcases” saga, when Dh2.5 billion in naira was smuggled out of the country in defiance of an anti-inflation ban on exporting currency. Buhari denies wrongdoing in either case.

In August 1985, the general was ousted by another military coup just as he was claiming Nigeria was reaping the benefits of his regime’s policies, especially in public discipline, the economy and the fight against corruption.

He spent much of the next three years in detention, but returned to favour in Nigeria’s chaotic 1990s. He was made head of a development body funded by oil revenues in a decade otherwise marked by promised, delayed and then cancelled democratic elections, another military coup and, finally in 1999, the transfer of power from military dictatorship to an elected government.

After more than 30 years of military rule, the route to viable democracy has understandably been far from smooth. Allegations of electoral malpractice cast doubt on the outcomes of polling in 1999, 2003 and 2007.

Buhari stood unsuccessfully for the presidency in the last two of those elections and in the less contentious 2011 poll. His emergence as a politician has coincided with his most striking changes of view. In 2001, he was quoted as advocating the implementation of Sharia in every corner of the country. But in the months leading up to his electoral triumph, he has stressed his support for religious freedom.

The other change is more significant. While rejecting overtures from Boko Haram in 2012 to act as an intermediary in talks with the government, he consistently criticised the force used against the group’s power base in northern Nigeria.

But his condemnation of Boko Haram’s kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls from a school in the northern Borno state, and of its relentless campaign of mass murder, could hardly have been more outspoken. Two months after denouncing the mass abduction, he escaped an assassination attempt by the group.

Given the abysmal security record of Jonathan’s government, the pledge to destroy Boko Haram may have weighed as heavily in voters’ minds as promises of social and economic reform. Certainly, when he assumes office on May 29, Buhari will carry a heavy burden of expectation from an impatient electorate.

weekend@thenational.ae

Follow us @LifeNationalUAE

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.